Terrance Hayes

National Book Award-Winning Poet

MacArthur "Genius" Award Recipient

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Terrance Hayes

Biography

“Terrance Hayes is a poet who reflects on race, gender, and family in works marked by formal dexterity and a reverence for history and the artistry of crafting verse. Employing an almost improvisational approach to writing, Hayes conjoins fluid, often humorous wordplay with references to popular culture both past and present in his subversion of canonical poetic forms.” —MacArthur Foundation

“First you’ll marvel at his skill, his near-perfect pitch, his disarming humor, his brilliant turns of phrase. Then you’ll notice the grace, the tenderness, the unblinking truth-telling just beneath his lines, the open and generous way he takes in our world.” —Cornelius Eady

One of the most compelling voices in American poetry, Terrance Hayes is the author of seven books of poetry: So to Speak (2023); American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018), a finalist for the 2018 National Book Award in Poetry and winner of the Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry; How to Be Drawn (2015), longlisted for the 2015 National Book Award in Poetry; Lighthead (2010), winner of the 2010 National Book Award in Poetry; Wind in a Box, winner of a Pushcart Prize; Hip Logic, winner of the National Poetry Series, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Award, and runner-up for the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets; and Muscular Music, winner of both the Whiting Writers Award and the Kate Tufts Discovery Award. He is also the author of To Float In The Space Between: Drawings and Essays in Conversation with Etheridge Knight (2018), which won the 2019 Etheridge Knight Criticism Collection award from The Poetry Foundation; and, most recently, Watch Your Language (2023), a fascinating collection of graphic reviews, illustrated prose, and visualized poetics addressing the last century of American poetry.

Hayes is the editor of the anthology Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems. He has been a recipient of many other honors and awards, including a 2014 MacArthur Foundation Genius Award, two Pushcart selections, eight Best American Poetry selections, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and the Guggenheim Foundation. His poems have appeared in literary journals and magazines including The New Yorker, Poetry, The American Poetry Review, Ploughshares, Fence, The Kenyon Review, Jubilat, Harvard Review, and Poetry. His poetry has also been featured on The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer.

Lighthead, his most innovative collection, investigates how we construct experience, presenting “the light-headedness of a mind trying to pull against gravity and time.” The citation for the National Book Award described it as a “dazzling mixture of wisdom and lyric innovation.” In Muscular Music, Hayes takes reader through a living library of cultural icons, from Shaft and Fat Albert to John Coltrane and Miles Davis. In Wind in a Box, he explores how identity is shaped by race, heritage, and spirituality, with the unifying motif being the struggle for freedom within containment. In Hip Logic, Hayes confronts racism, sexism, religion, family structure, and stereotypes with overwhelming imagery.

Hayes is an elegant and adventurous writer with disarming humor, grace, tenderness, and brilliant turns of phrase, very much interested in what it means to be an artist and a black man. He writes, “There are recurring explorations of identity and culture in my work and rather than deny my thematic obsessions, I work to change the forms in which I voice them. I aspire to a poetic style that resists style. In my newest work, I continue to be guided by my interests in people: in the ways community enriches the nuances of individuality; the ways individuality enriches the nuances of community.”

Professor of English at New York University, Hayes currently resides in New York City.

Short Bio

Terrance Hayes is the author of seven poetry collections: So to Speak; American Sonnets for My Past And Future Assassin, a finalist for the National Book Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and TS Eliot Prize; How to Be Drawn; Lighthead, winner of the 2010 National Book Award for poetry; Muscular Music, recipient of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award; Hip Logic, winner of the 2001 National Poetry Series, and Wind in a Box. His prose collection, To Float In The Space Between: Drawings and Essays in Conversation with Etheridge Knight, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and winner of the Pegasus Award for Poetry Criticism. His most recent book, Watch Your Language, is a fascinating collection of graphic reviews, illustrated prose, and visualized poetics addressing the last century of American poetry. Hayes has received fellowships from the MacArthur Foundation, Guggenheim Foundation, and Whiting Foundation, and is a professor of English at New York University.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

Watch Your Language

Essay, 2023

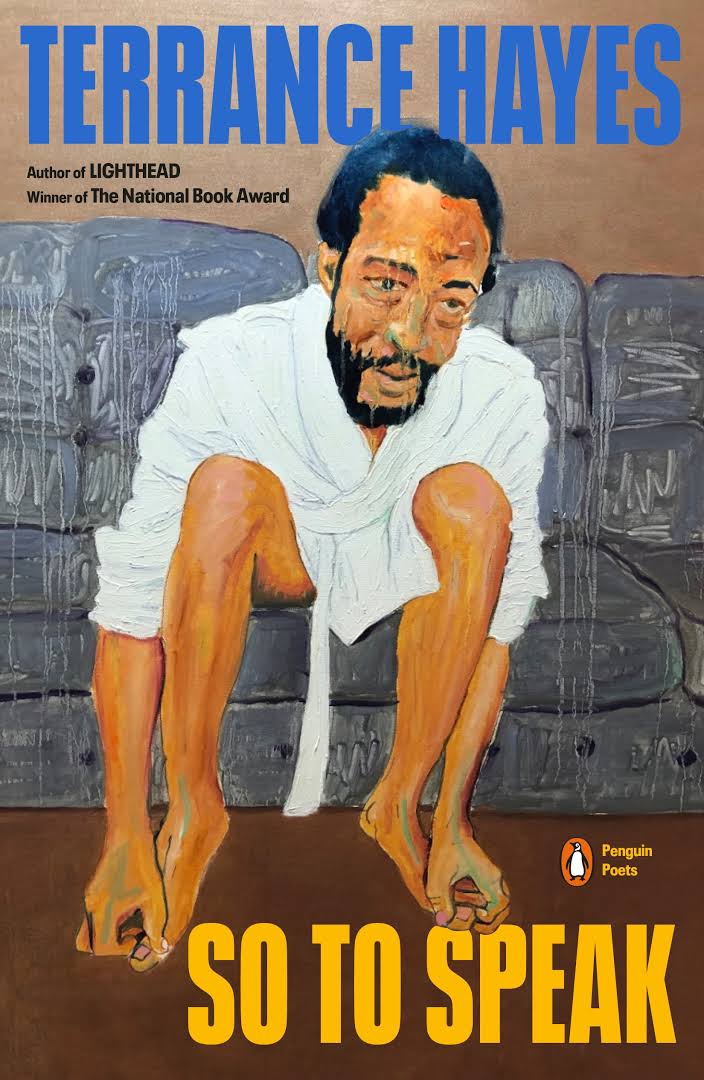

So to Speak

Poetry, 2023

Since the publication of his first collection, Muscular Music, in 1999, Terrance Hayes has been one of America’s most exciting and innovative poets, winning acclaim for sly, twisting, jazzy poems that put “invincibly restless wordplay at the service of strong emotions” (The New York Times Book Review).

A tree frog sings to overcome its fear of birds, talking cats tell jokes in the Jim Crow South, and a father addresses his daughter in the lyric fables, folk sonnets, quarantine quatrains, and ekphrastic do-it-yourself sestinas of So to Speak, Hayes’s seventh collection. Bob Ross paints your portrait, green beans bling in the mouth of Lil Wayne, and elegies for the late David Berman and George Floyd unfold amid the pandemic. These wondrous poems are lyric germinations of the often-incomprehensible predicaments of the present, as Hayes shapes language into figures of music and music into figures of language.

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin

Poetry, 2018

In seventy poems bearing the same title, Terrance Hayes explores the meanings of American, of assassin, and of love in the sonnet form. Written during the first two hundred days of the Trump presidency, these poems are haunted by the country’s past and future eras and errors, its dreams and nightmares. Inventive, compassionate, hilarious, melancholy, and bewildered–the wonders of this new collection are irreducible and stunning.

How to be Drawn

2015

In How to Be Drawn, his daring fifth collection, Terrance Hayes explores how we see and are seen. While many of these poems bear the imprint of Hayes’s background as a visual artist, they do not strive to describe art so much as inhabit it. Thus, one poem contemplates the principle of blind contour drawing while others are inspired by maps, graphs, and assorted artists. The formal and emotional versatilities that distinguish Hayes’s award-winning poetry are unified by existential focus. Simultaneously complex and transparent, urgent and composed, How to Be Drawn is a mesmerizing achievement.

Lighthead

Poetry, 2010

“[A] new collection in which the political and the personal converge in innovative and beautiful ways. The deservedly acclaimed Hayes returns in his fourth book with the kinds of sly, twisting, hip, jazzy poems his fans have come to expect, but also with a new somberness of tone and mature caution. “You can spend your whole life / doing no more than preparing for life and thinking / ‘Is this all there is?’” warns the book’s opening poem. Later, in a book that thinks hard about fatherhood, family, and mortality, Hayes asks, “Who cannot think // Our elegies are endless endlessly and the words / We put to them too often unheard and hurried?” Elsewhere, Hayes treats memory with his signature wit: I believe, as the elephant must,/ that everything is punctured by the tusks of Nostalgia.” The book also contains a surprisingly effective series of poems based on a form called pecha kucha, which, Hayes explains, is a type of Japanese business presentation in which the presenter must riff on a series of slides or images; Hayes adapts this form by bracketing the title or slide he’s riffing on (“The Magic of Magic” and “The Function of Fiction” are two examples) and following with a four- or five-line stanza. The poems free-associate through their triggers, but images and themes satisfyingly resurface. Hayes, now entering mid-career, remains one of our best poets.” —Publisher’s Weekly

To Float in the Space Between

2018

In these works based on his Bagley Wright lectures on the poet Etheridge Knight, Terrance Hayes offers not quite a biography but a compilation “as speculative, motley, and adrift as Knight himself.” Personal yet investigative, poetic yet scholarly, this multi-genre collection of writings and drawings enacts one poet’s search for another and in doing so constellates a powerful vision of black literature and art in America.

Wind in a Box

Poetry, 2006

“In this searching follow-up to the acclaimed Hip Logic, Hayes bluntly concludes that “everyone/ is a descendant of slaves” and, more tentatively, wonders “if outrunning your captors is not the real meaning of Race?” A series of “Blue” poems (“The Blue Bowie,” “The Blue Terrance”) considers twentieth-century representations of race, culling wisdom, and impressions from poet-activist Amiri Baraka, filmmaker and performer Melvin Van Peebles. and even Dr. Seuss: “Blacks in one box. Blacks in two box / Blacks on / Blacks stacked in boxes stacked on boxes.” Utilizing a range of forms and voices—Dante’s terza rima, jerky blues in the spirit of Langston Hughes, Frostian lyrics, contemporary prose poems—Hayes brilliantly delivers the aeolian flux promised by the title: “a signature of wind, / my type-written handwriting reconfiguring the past.” —Publisher’s Weekly

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Find a Headline, Write a Poem – NY Times

• Voluntary Imprisonment: Stephanie Burt on American Sonnets — Slate

• 2019 Firecracker Awards Finalists Announced — CLMP

• 2018 In Review: The Poetry I Was Grateful for in 2018 — The New Yorker

• Times Critics’ Top Books of 2018 – The New York Times

• Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets Shortlisted for T. S. Eliot Prize – The Guardian

• Sonnets That Reckon With Donald Trump’s America – New York Times

• Terrance Hayes Named NYT Magazine’s New Poetry Editor – NY Times Press Run

• I Am Your Negro Sometimes by Terrance Hayes – Yes! Magazine

• Terrance Hayes ponders self-image in new poetry collection – Michigan Daily

• Galaxies Inside His Head: Terrance Hayes by Stephen Burt — NY Times Magazine

• Meet Terrance Hayes — MacArthur Foundation

• National Book Award Citation for Lighthead

• Review of Lighthead — Weave Magazine

Listen to Audio

• Podcast: Political Writing from Terrance Hayes to the Anglo-Saxons – The Guardian

• Terrance Hayes Speaks To American Racism In Latest Collection Of Poetry – NPR

• Ars Poetica with Bacon — The New Yorker

• Poems are Music: Hayes on Winning the MacArthur Fellowship — NPR

Selected Writings

• Read “Capra Aegagrus Hircus” by Terrance Hayes – The New Yorker

• Read “George Floyd” by Terrance Hayes – The New Yorker

• Read “American Sonnets for my Past and Future Assassin” – The New Yorker

HOW TO DRAW A PERFECT CIRCLE

I can imitate the spheres of the model’s body, her head,

Her mouth, the chin she rests at the bend of her elbow

But nothing tells me how to make the pupils spiral

From her gaze. Everything the eye sees enters a circle,

The world is connected to a circle: breath spools from the nostrils

And any love to be open becomes an O. The shape inside the circle

Is a circle, the egg fallen outside the nest the serpent circles

Rests in the serpent’s gaze the way my gaze rests on the model.

In a blind contour drawing the eye tracks the subject

Without observing what the hand is doing. Everything is connected

By a line curling and canceling itself like the shape of a snake

Swallowing its own decadent tail or a mind that means to destroy itself,

A man circling a railway underpass before attacking a policeman.

To draw the model’s nipples I have to let myself be carried away.

I love all the parts of the body. There are as many curves

As there are jewels of matrimony, as many whirls as there are teeth

In the mouth of the future: the mute pearls a bride wears to her

wedding,

The sleeping ovaries like the heads of riders bunched in a tunnel.

The doors of the subway car imitate an O opening and closing,

In the blood the O spirals its helix of defects, genetic shadows,

But there are no instructions for identifying loved ones who go crazy.

When one morning a black man stabs a black transit cop in the face

And the cop, bleeding from his eye, kills the assailant, no one traveling

To the subway sees it quickly enough to make a camera phone

witness.

The scene must be carried on the tongue, it must be carried

On the news into the future where it will distract the eyes working

Lines into paper. This is what blind contour drawing conjures in me.

At the center of God looms an O, the devil believes justice is shaped

Like a zero, a militant helmet or war drum, a fist or gun barrel,

A barrel of ruined eggs or skulls. To lift anything from a field

The lifter bends like a broken O. The weight of the body

Lowered into a hole can make anyone say Oh: the onlookers,

The mother, the brothers and sisters. Omen begins with an O.

When I looked into my past I saw the boy I had not seen in years

Do a standing backflip so daring the onlookers called him crazy.

I did not see a moon as white as an onion but I saw a paper plate

Upon which the boy held a plastic knife and sopping meat.

An assailant is a man with history. His mother struggles

To cut an onion preparing a meal to be served after the funeral.

The onion is the best symbol of the O. Sliced, a volatile gas stings

The slicer’s eyes like a punishment clouding them until they see

What someone trapped beneath a lid of water sees:

A soft-edged world, a blur of blooms holding a coffin afloat.

The onion is pungent, its scent infects the air with sadness,

All the pallbearers smell it. The mourners watch each other,

They watch the pastor’s ambivalence, they wait for the doors to open,

They wait for the appearance of the wounded one-eyed victim

And his advocates, strangers who do not consider the assailant’s funeral

Appeasement. Before that day the officer had never fired his gun

In the line of duty. He was chatting with a cabdriver

Beneath the tracks when my cousin circled him holding a knife.

The wound caused no brain damage though his eyeball was severed.

I am not sure how a man with no eye weeps. In the Odyssey

Pink water descends the Cyclops’s cratered face after Odysseus

Drives a burning log into it. Anyone could do it. Anyone could

Begin the day with his eyes and end it blind or deceased,

Anyone could lose his mind or his vision. When I go crazy

I am afraid I will walk the streets naked, I am afraid I will shout

Every fucked up thing that troubles or enchants me, I will try to murder

Or make love to everybody before the police handcuff or murder me.

Though the bullet exits a perfect hole it does not leave perfect holes

In the body. A wound is a cell and portal. Without it the blood runs

With no outlet. It is possible to draw handcuffs using loops

Shaped like the symbol for infinity, from the Latin infinitas

Meaning unboundedness. The way you get to anything

Is context. In a blind contour it is not possible to give your subject

A disconnected gaze. Separated from the hand the artist’s eye

Begins its own journey. It could have been the same for the Cyclops,

A giant whose gouged eye socket was so large a whole onion

Could fit into it. Separated from the body the eye begins

Its own journey. The world comes full circle: the hours, the harvests,

When the part of the body that holds the soul is finally decomposed

It becomes a circle, a hole that holds everything: blemish, cell,

Womb, parts of the body no one can see. I watched the model

Pull a button loose on her jeans and step out of them

As one might out of a hole in a blue valley, a sea. I found myself

In the dark, I found myself entering her body like a delicate shell

Or soft pill, like this curved thumb of mine against her lips.

You must look without looking to make the perfect circle.

The line, the mind must be a blind continuous liquid

Until the drawing is complete.

—from How to Be Drawn

GOD IS AN AMERICAN

I still love words. When we make love in the morning,

your skin damp from a shower, the day calms.

Schadenfreude may be the best way to name the covering

of adulthood, the powdered sugar on a black shirt. I am

alone now on the top floor pulled by obsession, the ink

on m fingers. Sometimes what I feel has a difficult name.

Sometimes it is like the world before America, the kin-

ship of God’s fools and guardians, of hooligans; the dreams

of mothers with no children. A word can be the boot print

in a square of fresh cement and the glaze of morning.

Your response to my kiss is, I have a cavity. I am in

love with incompletion. I am clinging to your moorings.

Yes, I have a pretty good idea of what beauty is. It survives

all right. It aches like an open book. It makes it difficult to live.

—from Lighthead

WIND IN A BOX (one)

This ink. This name. This blood. This blunder.

This blood. This loss. This lonesome wind. This canyon.

This / twin / swiftly / paddling / shadow blooming

an inch above the carpet-. This cry. This mud.

This shudder. This is where I stood: by the bed,

by the door, by the window, in the night / in the night.

How deep, how often / must a women be touched?

How deep, how often, have I been touched?

On the bone, on the shoulder, on the brow, on the knuckle:

Touch like a last name, touch like a wet match.

Touch like an empty shoe and an empty shoe, sweet

and incomprehensible. This ink. This name. This blood

and wonder. This box. This body in a box. This blood

in the body. This wind in the blood.

—from Wind in a Box