Nickole Brown

Award-winning Poet & Educator

Winner of the Weatherford Award for Appalachian Poetry

Animal Advocate

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Nickole Brown

Biography

“Nickole Brown works the miracle of all good art, recording the unbearable even as she transforms it.” –Ellen Bass

“Brown [deftly] presents binaries as paradoxes: Southern femininity with Southern masculinity, Southern hospitality with Southern cruelty, Southern politeness with Southern plain speech.” –Lambda Literary Review

“Brown is a savior of wild creatures, a lover of animals, an angel in waiting, a rescuer, a storyteller.”—Washington Independent Review of Books

As a poet with an MFA in Fiction, Nickole Brown has a strong leaning toward cross-genre work, which was demonstrated in her debut, a novel-in-poems called Sister (Red Hen Press, 2007), published to great acclaim and reissued ten years later with a guide for survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Her second book, Fanny Says (BOA, 2015), is a biography-in-poems about her tough-as-new-rope grandmother from Kentucky. The collection won the Weatherford Award for Appalachian Poetry , and in an Oxford American review, Parneshia Jones wrote, “What makes this book essential to the growing cannon of writers confronting the American heritage is that these poems resist sympathy. . . . Here Brown is at her best—writing calamity with eloquence, speaking, in the same moment, Fanny’s complications and the poet’s claim on it. This book, like a grandmother’s love, is not always pretty, but it pulls you in and gives you so much truth.”

Most recently, Nickole Brown’s writing employs hybridity to examine the relationship between humans and animals in poems that operate like lean, lyric essays. Her work speaks in a Southern-trash-talking way about nature beautiful, damaged, dangerous, and in desperate need of saving. This includes two chapbooks: To Those Who Were Our First Gods, winner of the 2018 Rattle Prize, and her essay-in-poems, The Donkey Elegies (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2020). As Lia Purpura says, “Brown’s gorgeous language is infused with radical tenderness, authentic surprise, and restless curiosity. As acts of rescue, reclamation, and repair, her poems serve as extended heart-songs to all of us, and especially to the least of us.”

Brown has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kentucky Foundation for Women, and the Kentucky Arts Council. She received her MFA from the Vermont College, studied literature at Oxford University, and was the editorial assistant for the late Hunter S. Thompson. For ten years, Brown worked at the nonprofit, independent, literary press, Sarabande Books. She was, for many years after, co-editor of the Marie Alexander Poetry Series. She’s taught at a number of places, including Poets House, Hugo House, the Poetry Society of North Carolina, and 24 Pearl Street at The Fine Arts Works Center at Provincetown.

Currently, she lives in Asheville, NC, where she periodically volunteers at three different animal sanctuaries. There she also serves as President of the Hellbender Gathering of Poets, a nonprofit organization that aims to nurture a community hellbent on finding the words that protect and repair our climate-changed world. Their first annual environmental poetry festival is set to launch in Black Mountain, NC, in October of 2025.

In 2024, she’ll be the Writer-in-Residence at Hollins University, and after, she’ll teach—as she does every summer—at the Sewanee School of Letters MFA Program.

Visit Author Website

Videos

Publications

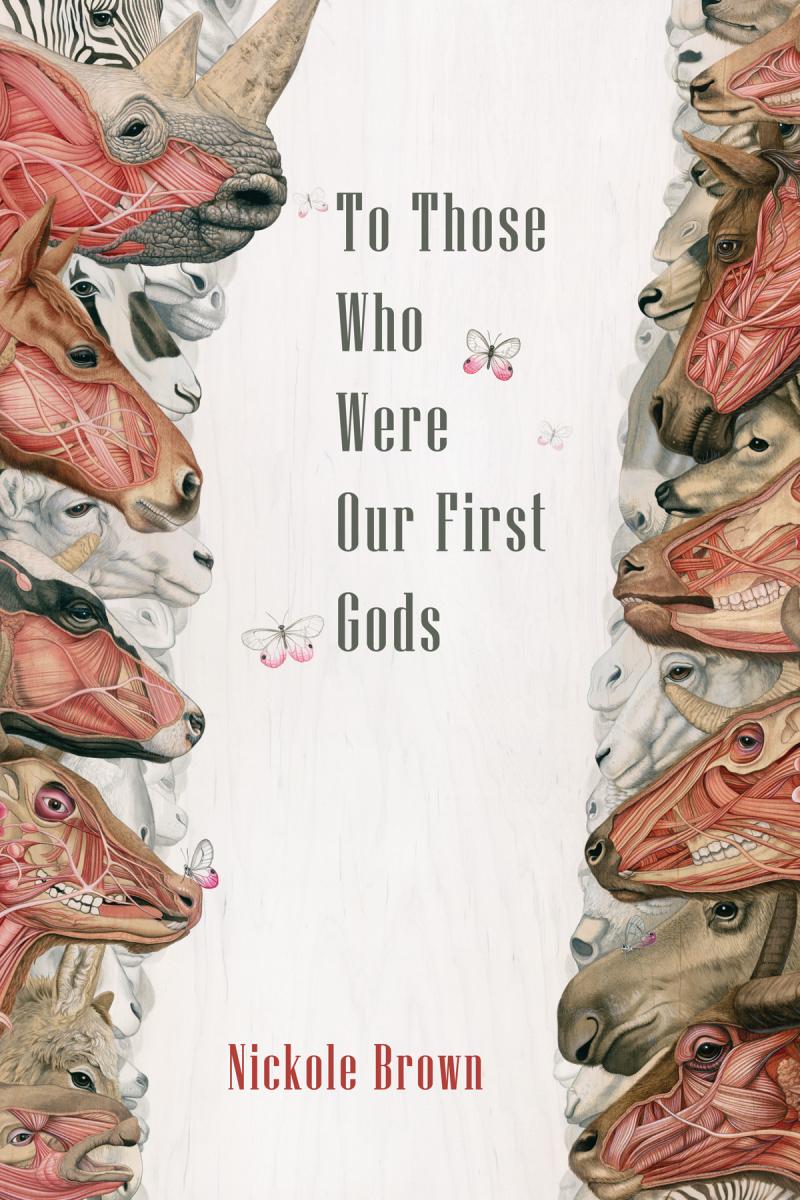

To Those Who Were Our First Gods

Poetry, 2020

For years, Nickole Brown has been at work on a bestiary of sorts, investigating the complex, interdependent, and often fraught relationship between human and non-human animals. In this chapbook you’ll find the first results of this project—nine poems from her new manuscript, all focusing on the experience of creatures in a world shaped (and increasingly destroyed) by us. These pieces—some of them long sequences that operate like lean, lyric essays—have their sight set upon the natural world. But these are not poems of privilege that gaze out the window from a place of comfortable remove. No, these are not the kind of pastorals that always made Brown (and most of the working-class folks from her Kentucky childhood) feel shut out of nature and the writing about it; instead they speak in a queer, Southern-trash-talking kind of way about nature beautiful, damaged, dangerous, and in desperate need of saving.

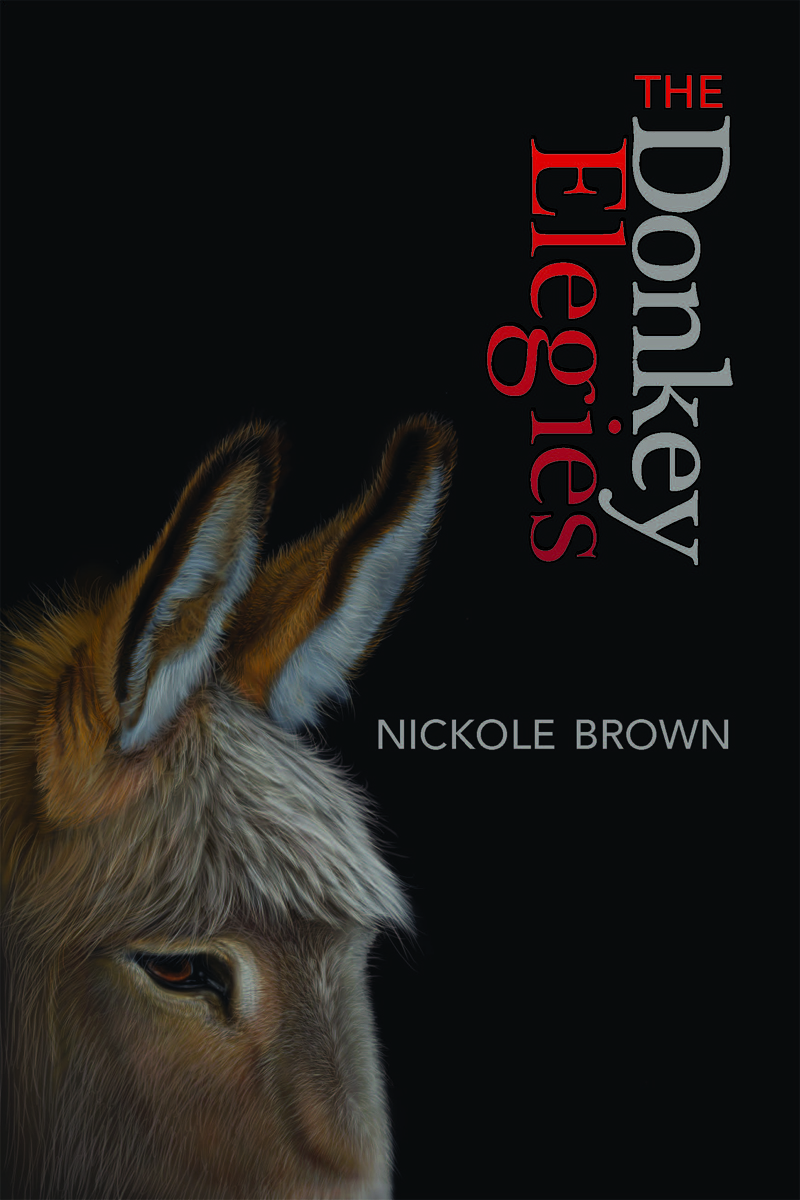

The Donkey Elegies

Poetry, 2020

The Donkey Elegies closely examines an animal’s history, tracing how one species hauled the stones that built our civilizations, plowed the fields that fed generations, and carted soldiers and weapons from war to war. The poems undo the brunt end of every lewd joke and unearth the sacred origins of a creature we rarely consider except as melancholy cartoon or dumb, stubborn brute. In these twenty-five linked pieces, a truth is made real: that we must cherish each living thing, each animal, each human being for all their worth.

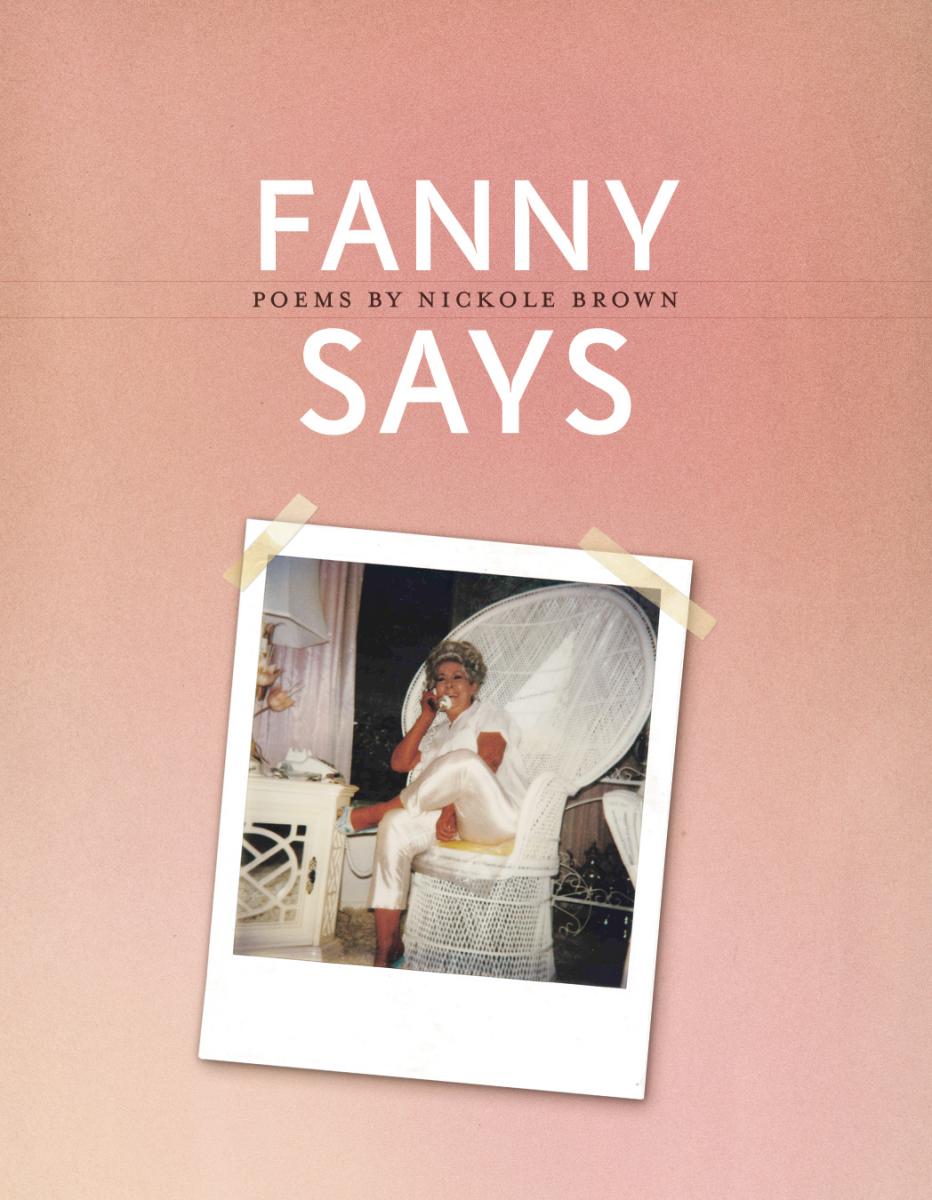

Fanny Says: A Biography in Poems

Poetry, 2015

In this “unleashed love song” to her late grandmother, Nickole Brown’s collection brings her sassy, bawdy, tough-as-new-rope grandmother to life. With hair teased to Jesus, mile-long false eyelashes, and a white Cadillac El Dorado decked with atomic-red leather seats, Fanny isn’t your typical granny rocking in a chair. A cross-genre collection that reads like a novel, this book is both a collection of oral history and a lyrical and moving biography that wrestles with the complexities of the South.

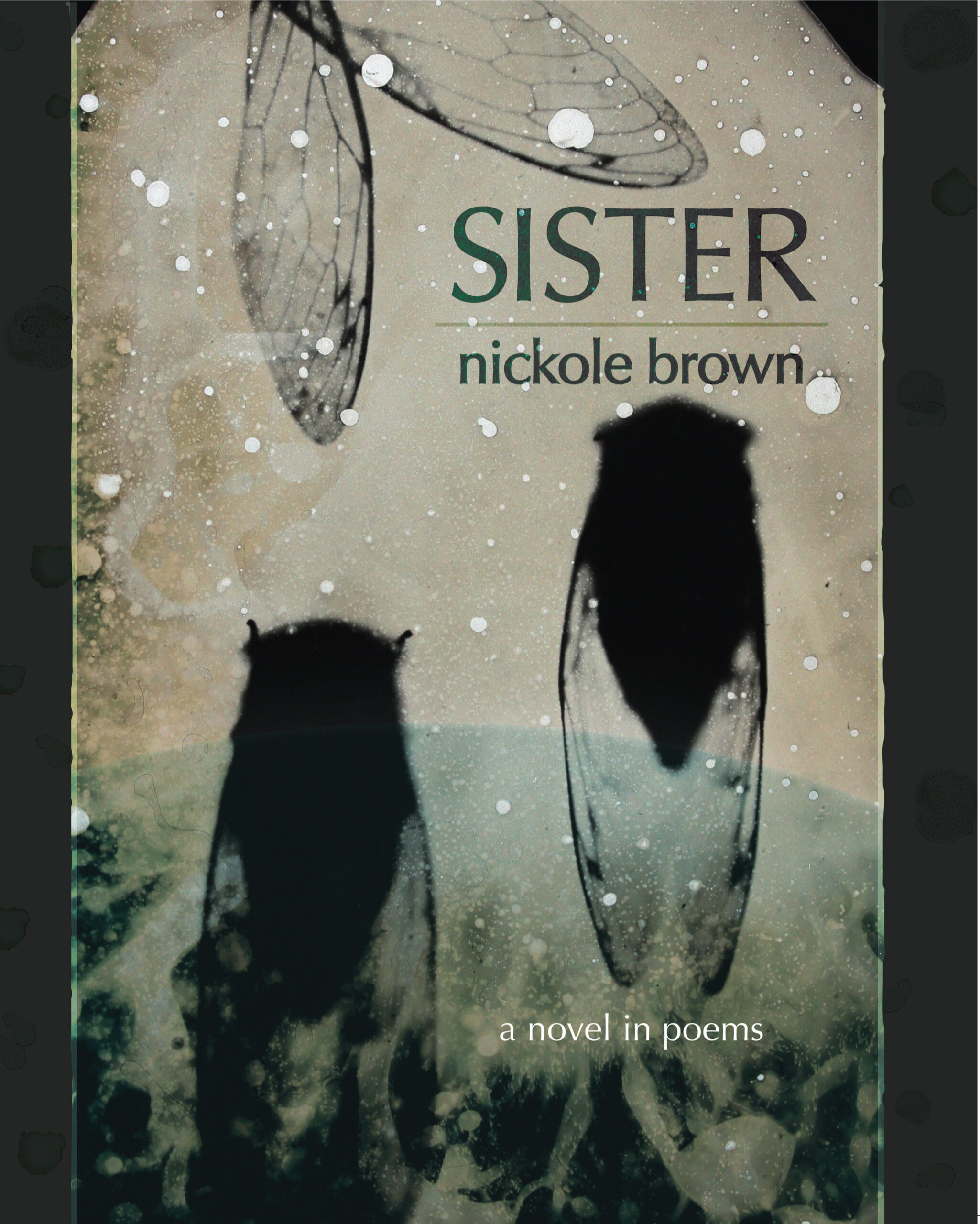

Sister

Poetry, 2007 & 2018

This new edition of Nickole Brown’s debut—published ten years after it first appeared—holds just as much relevancy and power today as it did a decade ago. In this special revised edition are all of the poems that first came to light in 2007, along with a discussion with the author and craft guide geared towards survivors writing through their own trauma.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Review: Fanny Says by Nickole Brown – Lambda Literary Review

• “Nickole Brown on Why the NEA Matters” – Poets.org

• Interview with Nickole Brown at FAWC – 24 Pearl Street Blog

• Call Your Body Home: An Interview with Nickole Brown – Nashville Review

• Book Review: Fanny Says by Nickole Brown – Los Angeles Review

Listen to Audio

• Julie Murphy Interviews Nickole Brown – The Hive Poetry Collective

• Episode 20: An Interview with Nickole Brown – Make No Bones

Selected Writings

• Read “On Memory and Survival” by Nickole Brown – Orion Magazine

• Read “How to Name a Bird” by Nickole Brown – Orion Magazine

• Read “Scare” by Nickole Brown – The Missouri Review

• Read “Grace” by Nickole Brown – Kenyon Review

Against Despair: The Kid Goat

1.

Reader, meet the two women who sunk

everything they had into taking in broken

animals—the gimpy and oozing

critters, the ugly, lopsided, tail-less

pets, urine-soaked and drooling, zested

with fleas, the matted and discarded

scrapheaps left growling and bucking, pissing

on everything, the good-riddance left roped

to a chain-link fence.

No, I take that back.

Instead I want you to be

those two: I want you crazy

enough to try to fix those beasts—

to feed and brush and bathe and dip and

sweetmilk them whole; I want you to try,

to always try, despite the odds,

just as you coaxed the docile

fat-blind pig up on legs that eventually

broke from his own inbred

weight, just as you spritzed the mites

off a mangy hen that would be limp

in the claws of a hawk

later that same day. On the hill, a stubborn

but sometimes gentle sheep grows

cold under a blue tarp,

and in your truck is a towel across

the backseat for your favorite

but neurotic-as-hell dog, how you rushed her

to the vet only to see her

put down.

2.

No, let me make this real—

Reader, I want you tired, every joint

in your body stiff and worn.

I want you to finally strip off

your filthy clothes. Then, I want you jolted

from sleep by a cry that in your dreams

sounds like an infant wailing

and, now awake,

sounds just the damn same.

3.

Go. Find that kid goat

bleating in the grainy dark.

He’s no bigger than a lap dog,

and on his fist-sized head are the buds

of his horns—tiny, like

two popcorn pieces of warm bone—

two bright spots, the only thing

you can see.

Flip on the switch.

Now, you know.

With bare hands I want you to

clear the froth from his lolling

tongue. I want you to grab a rag,

a sponge, the corner of your shirt—

anything you can find—to sop

up the liquid—so much of it

you can’t tell what’s what—be it

mucus or bile or vomit or blood—

as if every water has been brought up

for this giving-in, as if his body

is already a river and rushing

away. Now, use your arms:

it takes strength to steady the

convulsing of a thing even this young,

and then, once his gaze rolls back to

white, you know what to do, you know

your job: push together the furred slits

of his lids, close the extinguished

horizons of his eyes.

4.

Don’t play stupid. You knew

this was coming. You’ve seen it

enough times. You’re not dumb,

just desperate to try

to save this little meat

goat the farmer dumped

at your door,

too septic and riddled

with worms

to even be killed

to eat.

5.

Now, get on your knees.

Mop it up. As you wring

out the rags don’t push away

what you know of the sun,

let yourself admit the light,

how it made his ears pink and transparent

revealed the secret veins of leaves,

how you adored it when they periscoped

to your voice and he looked up to

give you the small meditations

of fresh milk and hay in his mouth.

Go on. Get sentimental

if you have to—have a good cry—

no one is here, and besides,

who would care? Because you try,

don’t you? You always try.

But always, that impossible

riddle, always the word

riddled with the word

worms, as if each whip-like body was curled

into a question, a wriggling puzzle, a mob

infestation of questions—parasites that love

a home so hard they turned that kid goat

anemic, fevering, stuttering with a murmuring

heart, shitting out a writhing

pile of larvae and eggs. Little sips—

little hooks—little burrows—this was how,

little by little, that little goat finally

collapsed, arched his throat back

as if to be slit, jerked his legs up into the

nothing like the fetus he was

just two months before.

6.

But here is the point: Do not ever

let yourself think it didn’t matter.

It mattered then

as it matters now, because until

this morning rose dull on the horizon

with this useless, good-for-nothing

goat now dead on your floor,

regardless, in spite of, no matter,

you fed a beast worthless, a real

lost cause not unlike

this whole stubborn,

beautiful, fucked-up planet

about to seize and drown

in its own melt.

7.

There really wasn’t a thing you could

do, but admit it: if you knew,

if you really could say he would not have died

last night but would certainly die

tomorrow, you’d force yourself

out of bed and do what it is you do:

you’d count his pills, warm his formula

over the stove, rake out his soiled pen,

and with arms wide, you’d bring him

a fresh bale of hay. Yes, that’s right: now say

his silly goat name—because, yes, every living

thing deserves a name—and you called him

Peanut, a playful way to say

he was a flake of the size he should have been,

so sick he did not jump or play as

he should but leaned his tiny face

exhausted into your leg. Now, bend

to stroke his scrawny

goat neck. Say, Good boy, Peanut.

We’ve got you. Now, now

there. Everything’s gonna be just fine.

You know it’s

a lie, but no matter.

Hope, you know by now,

is not a thing you feel

but something you do,

and this is your job. It’s what

you do; it’s what needs to be

done.