Emily Skillings

Acclaimed Poet & Teacher

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- List, Collage, Assemblage

- A Place for Poetry in Your Prose

- Feminist Intertextualities

- An Evening with Emily Skillings

Biography

“Although her language sometimes suggests she is from another planet, Emily Skillings knows how history happens on ours.” —John Ashbery

“Emily’s just trying to make us watch better. I love this poet’s compulsive sense of risk, her sense of humor. I love her dread. I love her love of detail. Her revulsion. So finally, basing this opinion on my exploration of this one writer, I’ll say that bitches are smart. Emily Skillings is very special. I’ll keep reading her.” — Eileen Myles

“One of Skillings’s greatest charms is her saucy, nonchalant feminist discontent.” —Publishers Weekly

“Having been a dancer has made me a better poet, as I feel I am able to access sensation, gravity, gesture and space in a heightened way.” —Emily Skillings

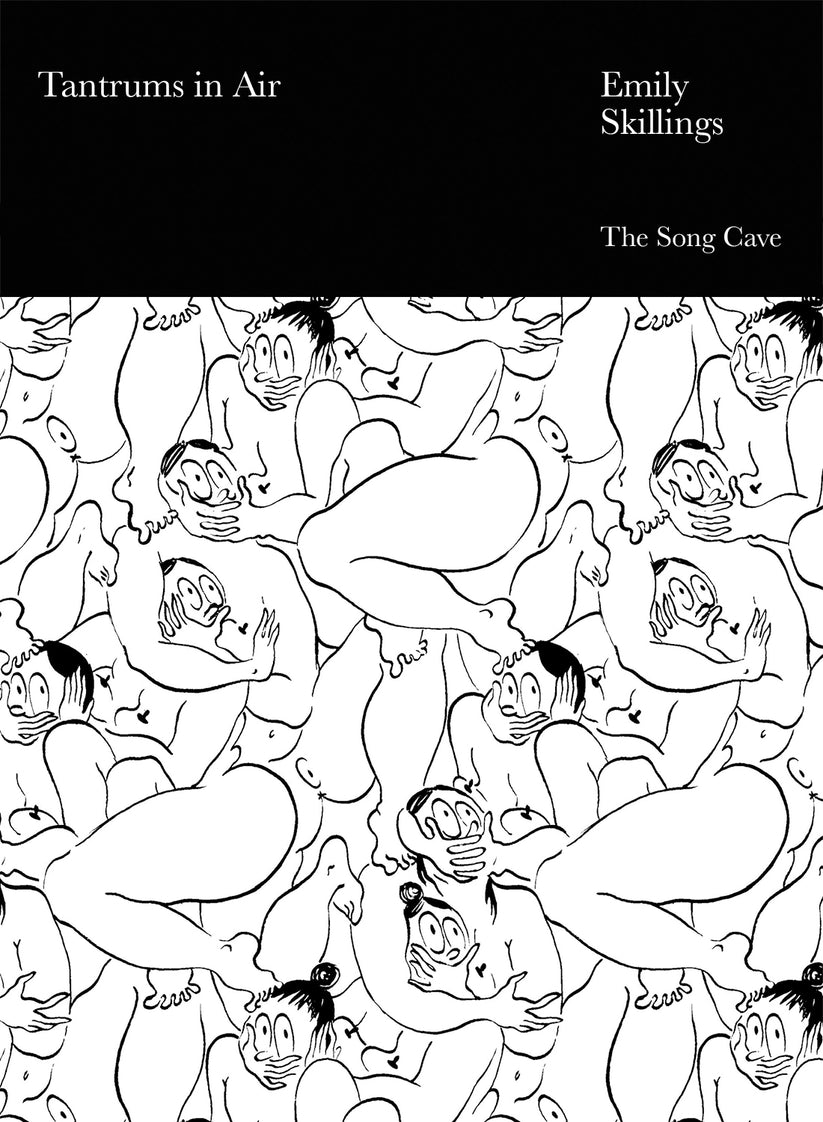

Poet and dancer Emily Skillings is the author of the poetry collections Tantrums in the Air (The Song Cave, 2025) and Fort Not (The Song Cave, 2017), which Publishers Weekly called a “fabulously eccentric, hypnotic, and hypervigilant debut,” and was shortlisted for The Believer 2018 Poetry Prize. The judges’s citation read: “This book is replete with lines that reverberate, like echoing prayers, at once a promise from God and to God.” In Emily’s own words, “Some of the shared attentions and themes of the book include depression, gender, color, painting and visual art, toxic white femininity, cloudiness, somatic experience, cantankerousness, jealousy, sex, light, America, collage, feelings without names, looming dread, boredom, water.”

Her highly anticipated second collection, Tantrums in the Air, writes through various poetic forms, reminding the reader how tenuous the line can be between a poem and, say, an Amazon review of the poet’s first book. Featuring a ballet in four acts–“part ghost, part sponge / a lump of pure refusal”—addresses to past loves—”I circle the circle / Of a compact mirror, open”—and an unconventional treatise on education, Tantrums in Air reinvents both what’s possible and what we should expect from poetry. Maggie Millner calls the work, “a brilliant, rivetingly original collection of poems, careening between high-femme camp performance, paranormal incantation, and sparkling dispatches from a mind mid-thought. These poems are obsessed with surfaces: those we touch and penetrate and barter, yes, but especially those we make using language, with its “blueblack liquid” and “opalescent scars” and “hooks and eyes / That open worlds.”

Skillings has also authored the chapbooks Backchannel (Poor Claudia, 2014) and Linnaeus: The 26 Sexual Practices of Plants. Of Backchannel, Todd Colby wrote: “delightful meditative mantra loops that leave me laugh-gasping with her ability to tickle and stab at the very same time. Skillings writes of canaries, shitsponges, bacteria rafts, and a site in Alaska known as “Dispersed Media Steepletop.” Who could ask for anything more? This chapbook is a funny and fierce debut worthy of your attention and love.”

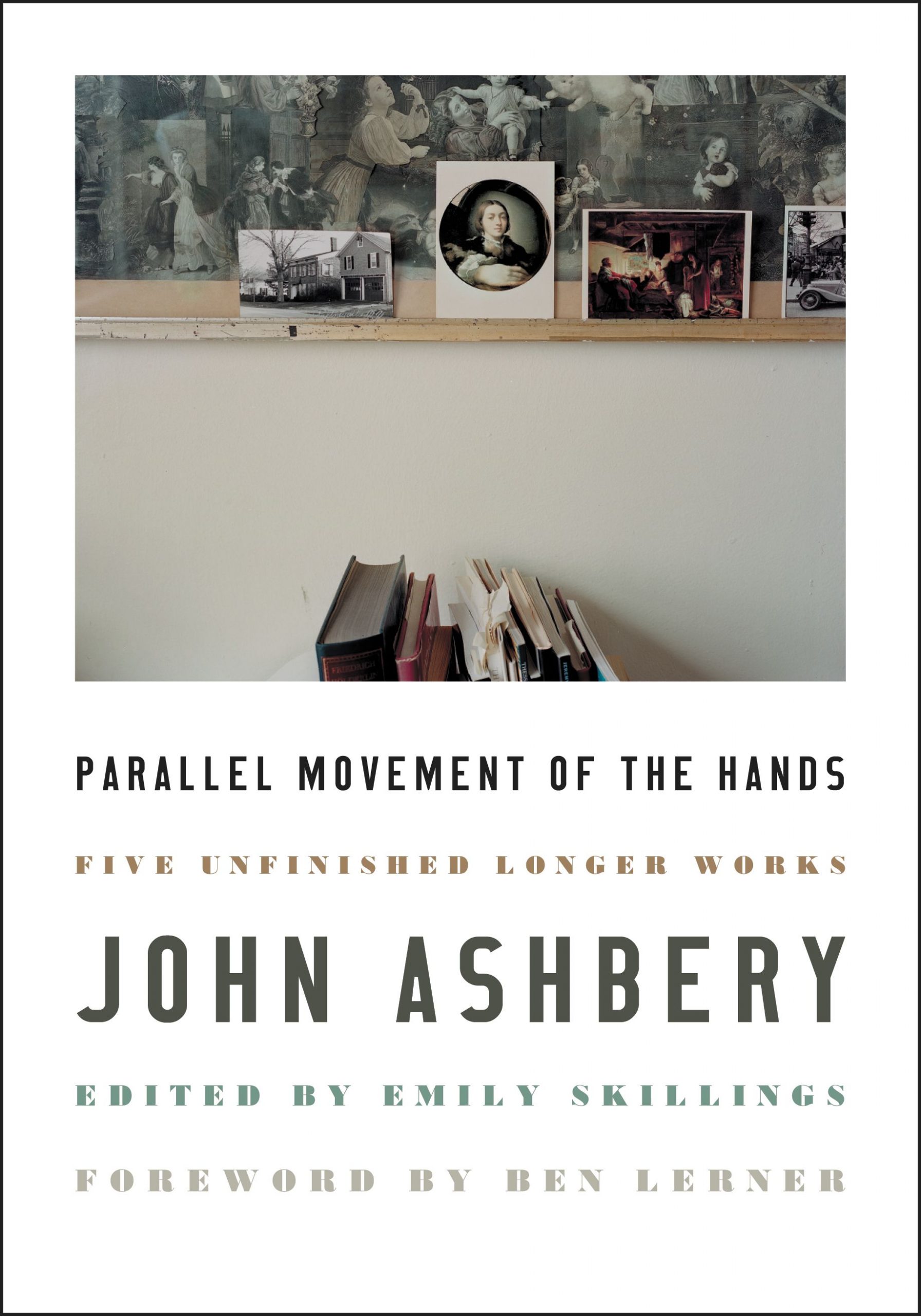

She is recently the editor of John Ashbery’s posthumous collection of poems Parallel Movement of the Hands: Five Unfinished Longer Works. Skillings is currently at work on a book-length poem sequence called Mother of Pearl about the environment, “and whether or not I want to eventually have children.”

Skillings is a member of the Belladonna* Collaborative, a feminist poetry collective, small press, and event series. She received her MFA from Columbia University, where she was a Creative Writing Teaching Fellow in 2017, and has taught creative writing at Yale University, Columbia University School of the Arts, Parsons School of Design, Poets House, and through Brooklyn Poets.

Skillings is based in Brooklyn, NY.

Short Bio

Emily Skillings is the author of the poetry collections Tantrums in the Air, Fort Not, and two chapbooks, Backchannel and Linnaeus: The 26 Sexual Practices of Plants. She is recently the editor of John Ashbery’s posthumous collection of poems Parallel Movement of the Hands: Five Unfinished Longer Works. Her poems can be found in Poetry, Harper’s, Boston Review, Brooklyn Rail, BOMB, Hyperallergic, The Rumpus, and jubilat. Skillings is a member of the Belladonna* Collaborative, a feminist poetry collective and small press. She received her MFA from Columbia University, where she was a Creative Writing Teaching Fellow in 2017, and has taught creative writing at Yale University, Columbia University School of the Arts, Parsons School of Design, Poets House, and through Brooklyn Poets. She is based in Brooklyn, NY.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

Tantrums in the Air

Poetry, 2025

Tantrums in Air is a brilliant, rivetingly original collection of poems, careening between high-femme camp performance, paranormal incantation, and sparkling dispatches from a mind mid-thought. These poems are obsessed with surfaces: those we touch and penetrate and barter, yes, but especially those we make using language, with its “blueblack liquid” and “opalescent scars” and “hooks and eyes / That open worlds.” For my money, Emily Skillings is simply one of the most exciting poets writing today. —Maggie Millner

Fort Not

Poetry, 2017

“Fort Not is a savagely brilliant debut.” —John Ashbery

In her highly anticipated debut collection, Fort Not, Emily Skillings creates an “atmosphere for encounter,” akin to searching for meaning through lip-reading. We soon realize that these poems are speaking to us in tones that appear elegantly improvisational. And while the poems may “shout from the periphery,” it is not without reason, but because of their desire to direct the reader to a created space—a world that allows for “curved logic,” “that dirty, off-gold color,” “middle-class nausea,” and “metallic power” to coexist. The mysteries here embrace a natural, physical music, pulling us into a moving current of painted images, poetic histories, and draped bodies evaporating to reveal others behind them, as quickly as they appear.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Emily Skillings Poetic Collaboration with NYC Ballet – NYCB

• Looking at Emily Skillings Through the Category of ‘Interesting’ — The Poetry Foundation

• 2016 Poetry Month: An Interview with Emily Skillings—Huffington Post

• The Whole Self: Our Thirteenth Annual Look at Debut Poets — Poets & Writers

Selected Writings

GIRLS ONLINE

The first line is a row of girls,

twenty-five of them, almost

a painting, shoulders overlapping,

angled slightly toward you.

One says: I’m myself here.

The others shudder and laugh

through the ribbon core that strings

them. They make a tone tighter

by drumming on their thighs and

opening their mouths. The girls

are cells. The girls are a fence,

a fibrous network. One by one

they describe their grievances.

Large hot malfunctioning

machines lie obediently at their sides.

Their shirts are various shades

of ease in the surrounding air,

which is littered with small cuts.

One will choose you, press you

into the ground. You may never

recover. The second-to-last line

has a fold in it. The last line is

the steady pour of their names.

POEM WITH ORPHEUS

Every word in this poem is a dead body.

Each word dies as you read it

and floats behind in a wooden canoe

that covers itself with itself

to make a coffin. A white, historical plane

knits above the dead word to shroud

and replace it. The poem before (this) point

is streaming and invisible. The rivulets

on which the coffin boats float

move backward forever. That last word (word)

and then (last) (that) (forever) (backward)

(move)—you killed those words.

You actually wrote this poem in its own blood.

The poem was alive just a minute ago

and then you arrived. You walked (here)

sluggishly against the wind of the underworld

to push against each heavy body. I’m trying

to (protect) these (words) (from) you (with)

(special armor). If you view this entire poem

in a mirror you will see death at work

as you see bees behind glass in a hive.

That last line is from Cocteau’s Orphée,

a film in which we come to know

all poems are direct transmissions

from the dead. When I transcribed it I reversed

its screen death and then (you) came

and looked at it, sending it back

to this blank page, a banal trauma,

a repeated rest on nothing.