Elisabet Velasquez

Award-winning Poet & Fiction Writer

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Elisabet Velasquez

Biography

“The candid, clear-eyed poetry contains powerful inquiries about diasporic Nuyorican identity and canny observations about the endemic social and racial inequities that surround her. Multilayered, heartbreaking, and hopeful coming of age.” —Horn Book, starred review

“The energy. The clarity. The beauty. Elisabet Velasquez brings it all. Clear-eyed, moving and funny.” –Jacqueline Woodson

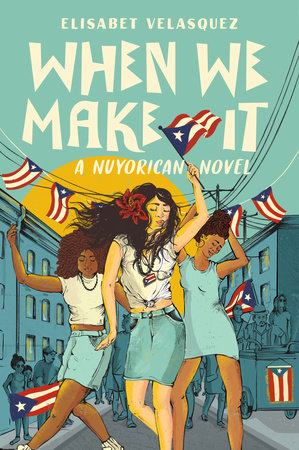

Elisabet Velasquez, Boricua writer from Bushwick, Brooklyn, is the author of When We Make It (Dial Books, 2021), winner of the YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults and a Gotham Book Prize finalist. A poet of presence, origin, and return, Velasquez crafts her narrative from a space of invitation: “I am constantly thinking about how I got here, wherever ‘here’ is at the moment. I sit down to write my poems with this question in mind: What does it mean for me to be an artist at this moment? I learned Spanish as a young adult and everyone would always tell me that I spoke it wrong. The problem was that I was told I spoke English wrong too. I believe part of why I became a poet was because it was impossible to speak wrong in a poem. A poem wasn’t going to grade my grammar or deny me a job because of my accent… I am enough in any language.”

Velasquez’s debut novel explores the experiences of a young first-generation Puerto Rican living in Bushwick, Brooklyn. As the protagonist questions the society around her, her Boricua identity, and the life she lives with determination and an open heart, she learns to celebrate herself in a way that she has long been denied. Of the work, Willie Perdomo said: “Velasquez renders the heart in conflict with itself, the swag and bilingual sonic charge of Bushwick, an uncompromising love, and the reality of being a young Puerto Rican woman, using poetry to make sense of conflict and chaos in her relentless search for truth. When We Make It is an unforgettable debut.”

Her work is featured in Muzzle Magazine, Winter Tangerine, Centro Voces, Latina Magazine, Longreads, We Are Mitú, Tidal, and Martín Espada’s anthology What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump. She was a 2017 Poets House Fellow and the 2017 winner of Button Poetry Video Poetry Contest. She was a 2019 Latinx fellowship recipient of The Frost Place.

Velasquez lives in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Short Bio

Elisabet Velasquez, Boricua writer from Bushwick, Brooklyn, is the author of When We Make It. Her work is featured in Muzzle Magazine, Winter Tangerine, Centro Voces, Latina Magazine, Longreads, We Are Mitú, Tidal, and Martín Espada’s anthology What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump. Velasquez lives in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

When We Make It

YA, 2021

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Stories As Mirrors: Interview with Elisabet Velasquez on When We Make It – School Library Journal

• Elisabet Velasquez’s Debut Novel Redefines What It Means for Latinas To Make It – Refinery29

• When We Make It: Raw, breathtaking, and brilliant – Kirkus Reviews

• Q&A: Elisabet Velasquez, Author of When We Make It – The Nerd Daily

Listen to Audio

• Chapter 22: How She Made It With Elisabet Velasquez – iHeart

• When We Make It by Elisabet Velasquez, Read by the Author – Literary Hub

Selected Writings

• Listen to “Professional Spanish Knocks on the Door” by Elisabet Velasquez – Everand

When We Make It (an excerpt)

How I Got My Name

Sarai

Let’s start the story where abandon meets faith.

Aight, so, boom. Check it.

I’m named after a homegirl

in the Bible who couldn’t have kids.

Her man Abram was all like:

Yo, Sarai, God promised me I would be the Father of Nations.

Sarai was all like:

Nah B, you must be buggin’, you know I can’t have no babies.

Our pastor says faith is believing in something

you can’t really see.

According to Mami,

we should never put our faith in men.

Mami was pregnant with me when Papi bounced

for some new chick & told Mami to have an abortion.

Abram got himself a new chick, too.

Got her pregnant and all that.

I guess Mami identified with Sarai’s fear and doubt—

& so I was born out of Mami’s faith & hope.

Mami

Mami is a round woman.

A square by any other definition.

No-nonsense, Pentecostal

with no patience for her own children most days.

There are three of us in total.

Danny, Estrella & Me. I am the youngest.

My sister Estrella said Mami’s depressed.

File this under “shit we don’t talk about.”

Pentecostals, we’re just supposed to pray

the sadness away.

¡Fuera! The pastor demands on prayer night.

¡Fuera! I imagine sadness is a bad singer

being kicked off the show

by el Chacal on Sábado Gigante.

Apparently, Jesus & Don Francisco

can save anything.

Once during church testimonio,

Mami gave Jesus mad credit

for saving her from Papi’s fists. ¡Amén! ¡Aleluya!

Now, Papi lives in the Bronx with his new wife.

Estrella uses the payphone

to collect call him all the time.

She says Papi is also Christian now

& that God forgave him

for beating on Mami & so we should too.

But Mami’s eyes never close right during prayer service

& I wonder what kind of God you have to be

to receive praise from the hands responsible for that.

How We Got Our Names

Estrella

Estrella was named after another woman

Papi was cheating on Mami with.

Nobody says that out loud though. But I can tell

by the way my sister’s name jumps off of Mami’s tongue

like one of those side chicks

on The Ricki Lake Show.

On my father’s tongue, Estrella matters.

Her name is a sloooow dance in Brooklyn.

Her name is a bullet that didn’t kill nobody.

Her name is the beeper alert that gets a call back.

Estrella is three years older than me.

She is sixteen but her body is not.

She got that it’s not my fault,

I thought you were older kind of body.

She is the kind of beautiful

that dique puts men in danger

or that makes men want to be dangerous.

The kind of beautiful Mami always wanted to be.

When we walk down Knickerbocker Ave.,

the men hiss like they are deflating at the sight of us.

They call Mami suegra. Mami can’t stand it.

Qué ridículo, she says.

She ain’t old enough to be nobody’s mother-in-law.

She shifts her body in front of Estrella’s, to protect her

or maybe so she can be seen first.