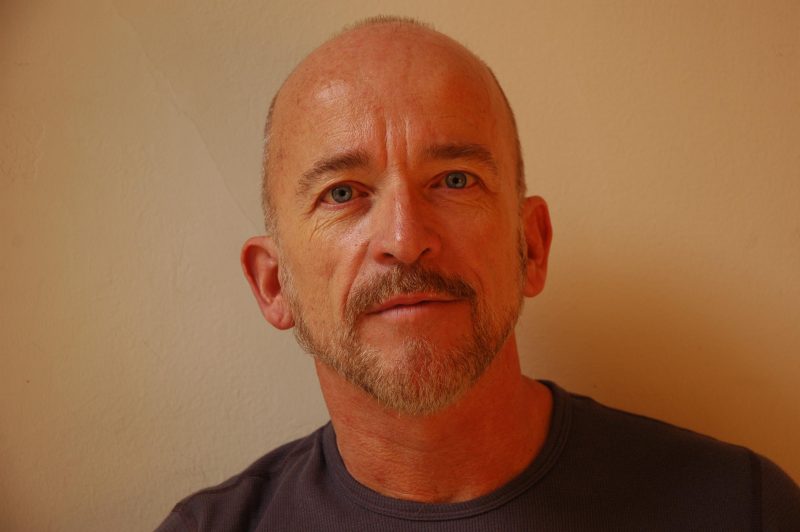

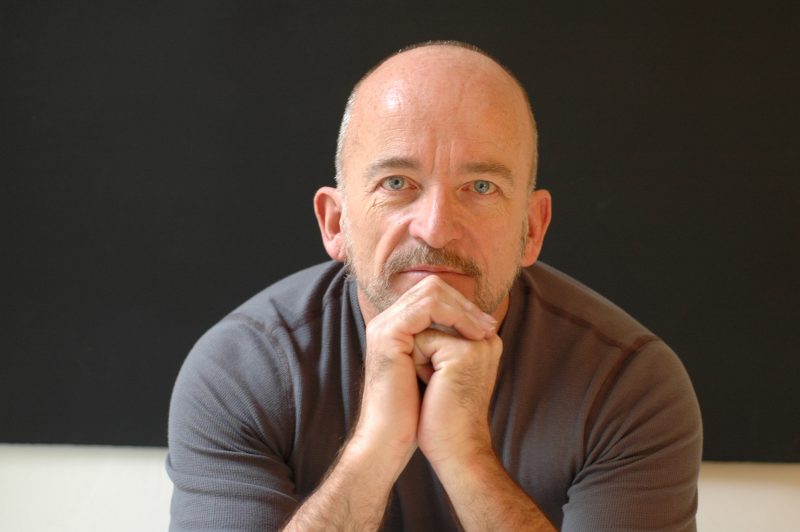

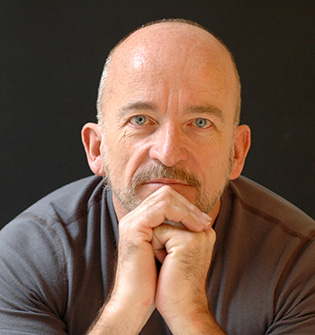

Mark Doty

Distinguished Poet & Essayist

NY Times Bestselling Memoirist

National Book Award Winner

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- The Poet’s Voice

- The Art of Description

- Dog Years: Grief and Healing

- Walt Whitman

- The Poetry of Visual Art

- The House of Memory: Tools for Memoirists

- New Forms for Poets and Nonfiction Writers

- An Evening with Mark Doty

Biography

“A new book of poems—or of anything—by Mark Doty is good news in a dark time. The precision, daring, scope, elegance of his compassion and of the language in which he embodies it are a reassuring pleasure.” —W. S. Merwin

“Doty pushes the boundaries of thought and form, always searching and considering and never wavering in his attempt to not only understand the world but determine the best way to ‘be’ in it.” —Booklist

“Doty brilliantly renders the majesty of distinctive creatures and the abiding presence of people and places that no longer exist. Apparitions and hard-won insights shape his hunger for the Divine.” —Washington Post

Praised by the New York Times for his “dazzling, tactile grasp of the world,” Mark Doty is a renowned author of poetry and prose. He is the author of three memoirs: the New York Times-bestselling Dog Years (HarperCollins, 2007), Firebird (1999), and Heaven’s Coast (1997), as well as a book about craft and criticism, The Art of Description: World Into Word, part of the popular “Art of” series published by Graywolf Press. Throughout his writings, he shows special interest in the visual arts, as is evident in his poems and also in his book-length essay, Still Life with Oysters and Lemon (2001). He most recent book is a memoir that centers on his poetic relationship with Walt Whitman, entitled What Is the Grass (W. W. Norton, 2020).

He is the author of nine books of poetry, most recently Deep Lane (W.W. Norton, 2015), a book of descents: into the earth beneath the garden, into the dark substrata of a life. But these poems seek repair, finally, through the possibilities that sustain the speaker above ground: art and ardor, animals and gardens, the pleasure of seeing, the world tuned by the word. Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems was published in 2008 and won the National Book Award for that year—in their citation, the National Book Award judges wrote, “Elegant, plain-spoken, and unflinching, Mark Doty’s poems in Fire to Fire gently invite us to share their ferocious compassion. With their praise for the world and their fierce accusation, their defiance and applause, they combine grief and glory in a music of crazy excelsis.” Doty is the first American poet to have won Great Britain’s T. S. Eliot Prize, for My Alexandria (1993), which also received both the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other collections of poetry include: Turtle, Swan (1987); Atlantis (1995); Sweet Machine (1998); Source (2001); and the critically acclaimed volume, School of the Arts (HarperCollins, 2005).

Former US Poet Laureate Philip Levine remarked, “If it were mine to invent the poet to complete the century of William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens, I would create Mark Doty just as he is, a maker of big, risky, fearless poems in which ordinary human experience becomes music.” And Mary Oliver said: “One of the things that has been constant about Mark Doty’s work, poetry and prose, is his intense search for the exact word or phrase, of whatever issue, which lead him (and us) into the very furnace of meaning within the human story.”

In addition to the National Book Award, Doty has also received two NEA fellowships, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Writers Award, a Lila Wallace/Readers Digest Award, and the Witter Byner Prize. As the award citation for the last of these noted, “Mark Doty’s poems extend the range of the American lyric.” In 2011 Doty was elected a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets.

Doty is a Distinguished Professor at Rutgers University, and also teaches in NYU’s low-residency MFA program in Paris.

Short Bio

Mark Doty is the author of nine books of poetry, including Deep Lane (April 2015), Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems, which won the 2008 National Book Award, and My Alexandria, winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the T.S. Eliot Prize in the UK. He is also the author of four memoirs: the New York Times-bestselling What Is the Grass, Dog Years, Firebird, and Heaven’s Coast, as well as a book about craft and criticism, The Art of Description: World Into Word. Doty has received two NEA fellowships, Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships, a Lila Wallace/Readers Digest Award, and the Witter Byner Prize.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

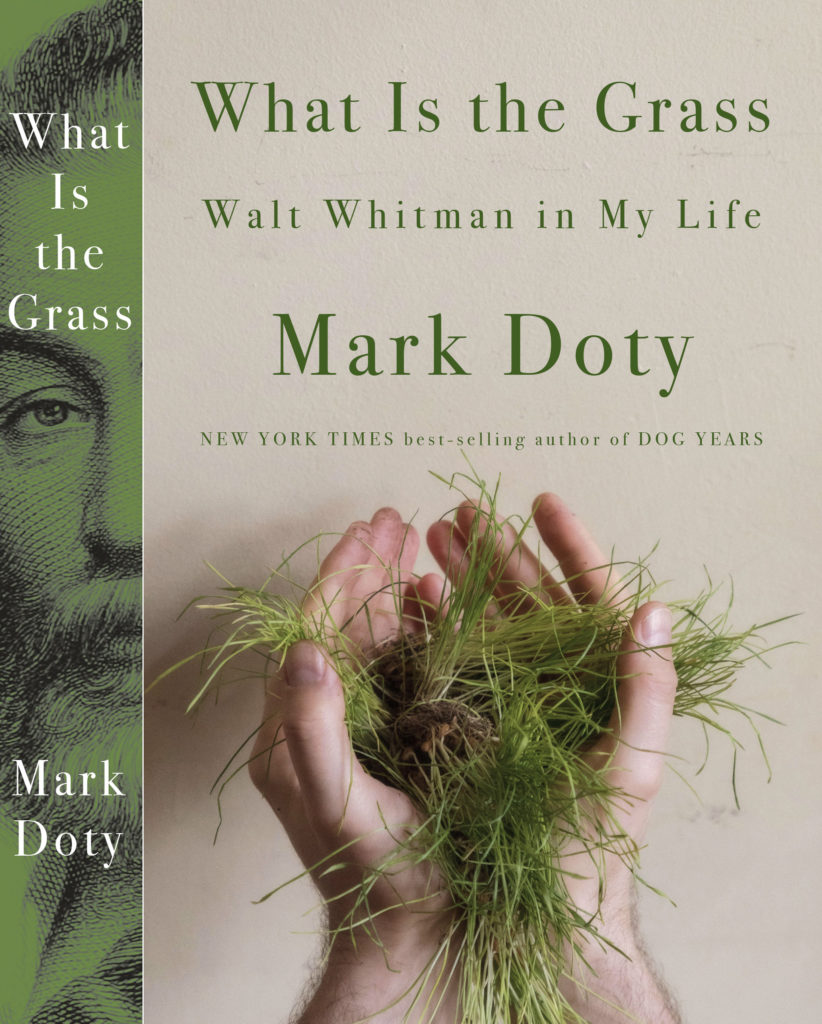

What is the Grass

Memoir, 2020

Mark Doty has always felt haunted by Walt Whitman’s bold, perennially new American voice, and by his equally radical claims about body and soul and what it means to be a self. In What Is the Grass, Doty—a poet, a New Yorker, and an American—keeps company with Whitman and his Leaves of Grass, tracing the resonances between his own experience and the legendary poet’s life and work. What is it then between us? Whitman asks. In search of an answer, Doty explores spaces—both external and internal—where he finds the poet’s ghost. He meditates on desire, love, and the mysterious wellsprings of the poet’s enduring work: a radical experience of transformation and enlightenment, queer sexuality, and an obsession with death, as well as unabashed love for a great city and for the fresh, rowdy character of American speech. In riveting close readings threaded with personal memoir and illuminated by awe, Doty reveals the power of Whitman’s persistent presence in his life and in the American imagination at large.How does a voice survive death? What Is the Grass is a conversation across time and space, a study of the astonishment one poet finds in the accomplishment of another, and an attempt to grasp Whitman’s deeply hopeful vision of human possibility.

Deep Lane

Poetry, 2015

“When Mark Doty begins one of his extraordinary Deep Lane poems with ‘Into Eden came the ticks,’ not only the ticks of the natural world but the ticking of the underworld come to mind. Doty has never ceased searching everywhere for truth and awe, two words that constitute a definition of revelation. The perfect avatar for this brilliant book’s revelatory wonders may well be ‘a deer’s head floating in the bay, wreathed with flowers.’ Deep Lane is earthly, unearthly, and even when brutal, beautiful. These are sensational new poems.” —Terrance Hayes

Mark Doty’s poetry has long been celebrated for its risk and candor, an ability to find transcendent beauty even in the mundane and grievous, an unflinching eye that—as Philip Levine says—“looks away from nothing.” In the poems of Deep Lane the stakes are higher: there is more to lose than ever before, and there is more for us to gain. “Pure appetite,” he writes ironically early in the collection, “I wouldn’t know anything about that.” And the following poem answers:

Down there the little star-nosed engine of desire

at work all night, secretive: in the morning

a new line running across the wet grass, near the surface,

like a vein. Don’t you wish the road of excess

led to the palace of wisdom, wouldn’t that be nice?

Deep Lane is a book of descents: into the earth beneath the garden, into the dark substrata of a life. But these poems seek repair, finally, through the possibilities that sustain the speaker aboveground: gardens and animals, the pleasure of seeing, the world tuned by the word. Time and again, an image of immolation and sacrifice is undercut by the fierce fortitude of nature: nature that is not just a solace but a potent antidote and cure. Ranging from agony to rapture, from great depths to hard-won heights, these are poems of grace and nobility.

The Art of Description

Essays, 2010

“It sounds like a simple thing, to say what you see,” Mark Doty begins. “But try to find words for the shades of a mottled sassafras leaf, or the reflectivity of a bay on an August morning, or the very beginnings of desire stirring in the gaze of someone looking right into your eyes . . .” Doty finds refuge in the sensory experience found in poems by Blake, Whitman, Bishop, and others. The Art of Description is an invaluable book by one of America’s most revered writers and teachers.

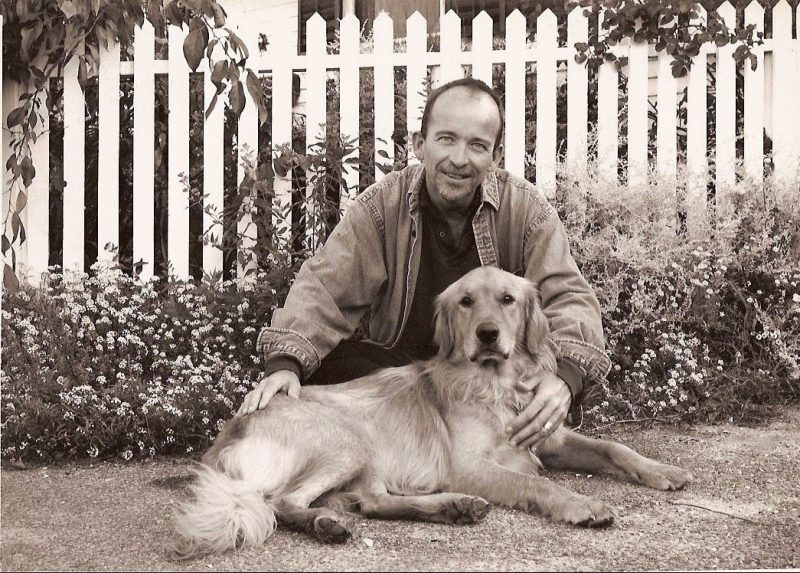

Dog Years: A Memoir

Memoir, 2007

“With a marvelous ability to present the pain of mourning with a poet’s delicate hand, and an irrepressible instinct for joy, Doty delivers a soulful love story which illuminates no less than the big human mysteries: attachment, death, grief, loyalty, happiness.” —Publishers Weekly

“To be loved by Doty, as a human or a canine, is to be elevated into a realm of utter glory, where one is cherished and cradled, sheltered and supported, and, most of all, where one’s very essence is acknowledged and appreciated in a manner both simple and sublime. In his latest elegant and elegiac memoir, Doty recounts how the love of two dogs, Arden and Beau, sustained him during times of his most grievous losses, and how he, in turn, came to nurse them through their inevitable years of failing health. On the brink of a life-threatening depression, Doty recognized the necessity of caring for his beloved dogs, which then metamorphosed into a life-affirming realization that he was, in fact, the one being attended. Sprinkled among poignant and merry anecdotes about typical and peculiar doggie behavior are Doty’s tender yet cogent reflections on the underlying truths such conduct reveals about the canine species, observations that transcendently celebrate the essential connection between man and pet.” —Carol Haggas, Booklist

Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems

Poetry, 2008

“Elegant, plain-spoken, and unflinching, Mark Doty’s poems in Fire to Fire gently invite us to share their ferocious compassion. With their praise for the world and their fierce accusation, their defiance and applause, they combine grief and glory in a music of crazy excelsis.” —National Book Award Judges Citation

National Book Award winner, Fire to Fire, collects the best of Mark Doty’s seven books of poetry, along with a generous selection of new work. Our mortal situation, the evanescent beauty of the world, desire’s transformative power, the dignity of the powerless, the instructive presence of animals, and art’s ability to give shape to human lives: Doty’s subjects echo and develop across twenty years of poems that speak to the crises and possibilities of our times.

School of the Arts

Poetry, 2006

With School of the Arts, Mark Doty’s darkly graceful seventh collection, the poet reinvents his own voice at midlife, finding his way through a troubled passage. At once witty and disconsolate—formally inventive, acutely attentive, insistently alive—this is a book of fierce vulnerability that explores the ways in which we are educated by the implacable powers of time and desire in a world that constantly renews itself.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Deep Pain in Mark Doty’s Deep Lane – Slate

• A Second Plague: The Echoes of AIDS in the COVID Era – GQ

• 50 Unapologetically Queer Authors Share the Best LGBTQ Books of All Time — Oprah Mag

• Interview about Deep Lane — Shelf Awareness

• Interview with Mark Doty — Boston Globe

• Interview: The Lessons of Objects — Kenyon Review

• Review of Fire to Fire — Christian Science Monitor

• Review of Dog Years — New York Times

• Review of Dog Years — The Guardian

• Review of School of the Arts — Publishers Weekly

• “Here in Hell,” Essay by Mark Doty — Modern American Poetry

Listen to Audio

• Mark Doty Pays Tribute to Walt Whitman in What is the Grass – NPR

• Poet Mark Doty On Love, Loss and Leaving Things Unsaid – WUWM (Milwaukee Public Radio)

• Mark Doty Reads “Deep Lane” — The New Yorker

Selected Writings

WHAT IS THE GRASS?

On the margin

in the used text

I’ve purchased without opening

— pale green dutiful vessel —

some unconvinced student has written,

in a clear, looping hand,

Isn’t it grass?

How could I answer the child?

I do not exaggerate,

I think of her question for years.

And while first I imagine her the very type

of the incurious, revealing the difference

between a mind at rest and one that cannot,

later I come to imagine that she

had faith in language,

that was the difference: she believed

that the word settled things,

the matter need not be looked into again.

And he who’d written his book over and over, nearly ruining it,

so enchanted by what had first compelled him

— for him the word settled nothing at all.

— from Deep Lane

PESCADERO

The little goats like my mouth and fingers,

and one stands up against the wire fence, and taps on the fence-board

a hoof made blacker by the dirt of the field,

pushes her mouth forward to my mouth,

so that I can see the smallish squared seeds of her teeth, and the bristle-whiskers,

and then she kisses me, though I know it doesn’t mean “kiss,”

then leans her head way back, arcing her spine, goat yoga,

all pleasure and greeting and then good-natured indifference: She loves me,

she likes me a lot, she takes interest in me, she doesn’t know me at all

or need to, having thus acknowledged me. Though I am all happiness,

since I have been welcomed by the field’s small envoy, and the splayed hoof,

fragrant with soil, has rested on the fence-board beside my hand.

— from Deep Lane

THE ART OF DESCRIPTION (Essay excerpt)

It sounds like a simple thing, to say what you see. But try to find words for the shades of a mottled sassafras leaf, or the reflectivity of a bay on an August morning, or the very beginning of desire stirring in the game of someone looking right into your eyes, and it immediately becomes clear that all we see is slippery, nuanced, elusive. As Susan Mitchell says, “The world is wily, and doesn’t want to be caught.”

Perception is simultaneous and layered, and to single out any aspect of it for naming is to turn your attention away from myriad other things, those braiding elements of the sensorium—that continuous, complex response to things perpetually delivered by the senses, the encompassing sphere that is such a large part of our subjectivity.

DOG YEARS (Memoir Excerpt)

No dog has ever said a word, but that doesn’t mean they live outside the world of speech. They listen acutely. They wait to hear a term—biscuit, walk—and an inflection they know. What a stream of incomprehensible signs passes over them as they wait, patiently, for one of a few familiar words! Because they do not speak, except in the most limited fashion, we are always trying to figure them out. The expression is telling: to “figure out” is to make figures of speech, to invent metaphors to help us understand the world. To choose to live with a dog is to agree to participate in a long process of interpretation—a mutual agreement, though the human being holds most of the cards.