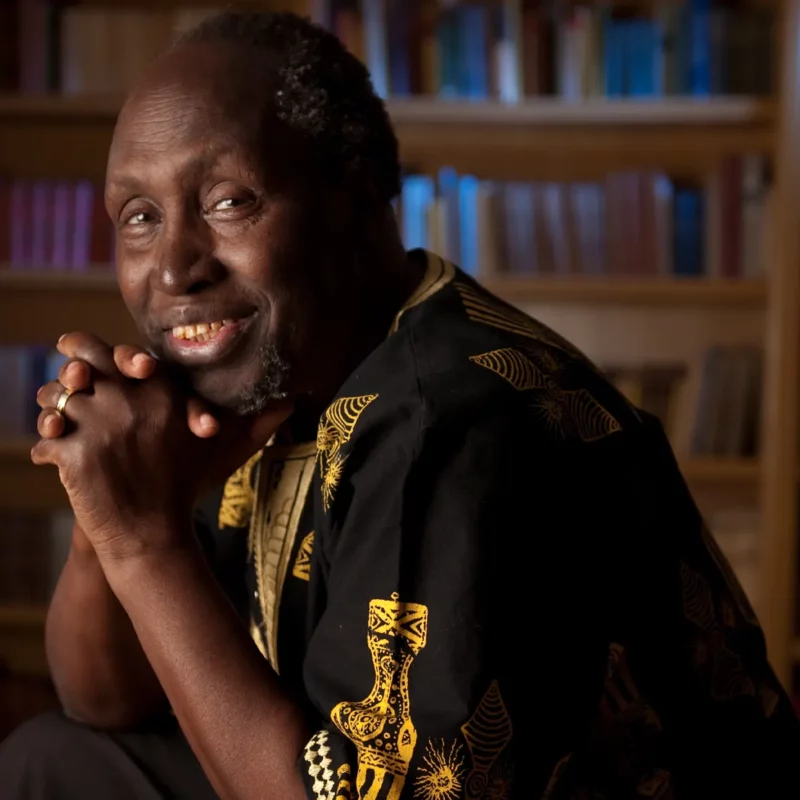

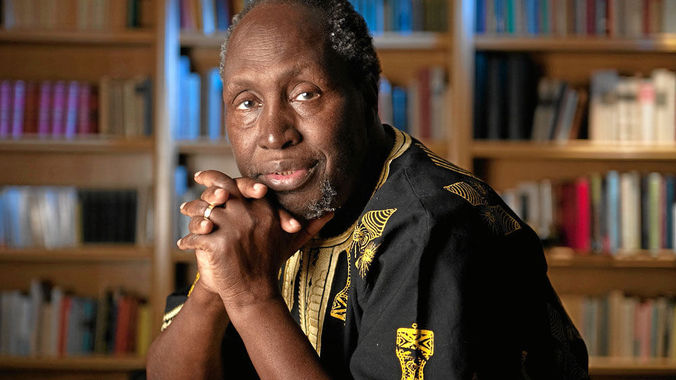

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Novelist & Memoirist

Literary & Social Activist

Nobel Prize Nominee

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Biography

“In his crowded career and eventful life, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has enacted, for all to see, the paradigmatic trials and quandaries of a contemporary African writer, caught in sometimes implacable political, social, racial, and linguistic currents.” —John Updike

“Extraordinary. Among the major works of history and literature of our time.” —The Washington Post

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was born in Kenya and educated at Makerere University College (then a campus of London University), Kampala, Uganda, and the University of Leeds, Britain. The Kenya of his birth and youth was a British settler colony (1895-1963). As an adolescent, he lived through the Mau Mau War of Independence (1952-1962), the central historical episode in the making of modern Kenya and a major theme in his early works.

Ngũgĩ burst onto the literary scene in East Africa with the performance of his first major play, The Black Hermit, at the National Theatre in Kampala, Uganda, in 1962, as part of the celebration of Uganda’s Independence.

He is the author of the novel Weep Not Child (1964), published to critical acclaim; followed by his second novel, The River Between (1965). His third, A Grain of Wheat (1967), was a turning point in the formal and ideological direction of his works. Multi-narrative lines and multi-viewpoints unfolding at different times and spaces replace the linear temporal unfolding of the plot from a single viewpoint. The collective replaces the individual as the center of history.

His first novel in ten years, Petals of Blood (1977), paints a harsh and unsparing picture of life in neo-colonial Kenya. It was received with even more emphatic critical acclaim in Kenya and abroad. The Kenya Weekly Review described it as “this bomb shell” and the Sunday Times of London as capturing every form and shape that power can take. The same year Ngũgĩ’s controversial play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii, was performed at Kamirithu Educational and Cultural Center, Limuru, in an open air theatre, with actors from the workers and peasants of the village.

Sharply critical of the inequalities and injustices of Kenyan society, publicly identified with unequivocally championing the cause of ordinary Kenyans, and committed to communicating with them in the languages of their daily lives, Ngũgĩ was arrested and imprisoned without charge at Kamiti Maximum Security Prison in 1977. An account of those experiences is to be found in his memoir, Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary (1982). It was at Kamiti Maximum Prison that Ngũgĩ made the decision to abandon English as his primary language of creative writing and committed himself to writing in Gikuyu, his mother tongue. In prison, and following that decision, he wrote on toilet paper the novel Caitani Mutharabaini (1981) translated into English as Devil on the Cross (1982).

After Amnesty International named him a Prisoner of Conscience, an international campaign secured his release a year later. However, the Moi dictatorship barred him from jobs at colleges and university in the country. While Ngũgĩ was in Britain for the launch and promotion of Devil on the Cross, he learned about the Moi regime’s plot to eliminate him on his return, or as coded, give a red carpet welcome on arrival at Jomo Kenyatta Airport. This forced him into exile, first in Britain (1982 –1989), and then the U.S. after (1989-2002), during which time, the Moi dictatorship hounded him trying, unsuccessfully, to get him expelled from London and from other countries he visited. In 1986, at a conference in Harare, an assassination squad outside his hotel in Harare was thwarted by the Zimbwean security. His next Gikuyu novel, Matigari (1986), lead to the Moi dictatorship’s removal of wa Ngũgĩ’s books from all educational institutions and Kenyan Bookshops.

Ngũgĩ has continued to write prolifically, publishing what some have described as his crowning achievement, Wizard of the Crow (2006), an English translation of the Gikuyu language novel, Murogi wa Kagogo. wa Thiong’o’s books have been translated into more than thirty languages and they continue to be the subject of books, critical monographs, and dissertations.

In exile, Ngũgĩ worked with the London based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya (1982-1998), which championed the cause of democratic and human rights in Kenya. In between, he was Visiting Professor at Byreuth University; and Writer in Residence, for the Borough of Islington, London; and took time to study film, at Dramatiska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden. After 1988, Ngũgĩ became Visiting Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Yale in between holding The Five Colleges (Amherst, Mount Holyoke, New Hampshire, Smith, East Massachusetts) Visiting Distinguished Professor of English and African Literature. He then became Professor of Comparative Literature and Performance Studies at New York University where he also held the Erich Maria Remarque Professor of languages, from where he moved to his present position at the University of California Irvine. He remained in exile for the duration of the Moi Dictatorship 1982-2002. When he and his wife, Njeeri, returned to Kenya in 2004 after twenty-two years in exile, they were attacked by four hired gunmen and narrowly escaped with their lives.

He is recipient of many honors, including the 2001 Nonino International Prize for Literature and eleven honorary doctorates. Currently, Ngũgĩ is a Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

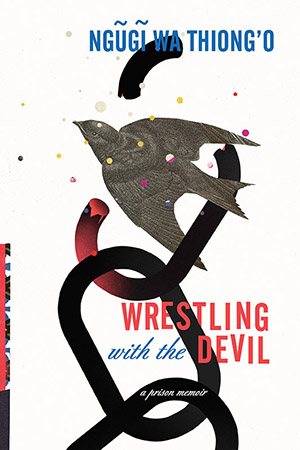

Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir

Memoir, 2018

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s powerful prison memoir begins literally half an hour before his release on December 12, 1978. In one extended flashback he recalls the night, a year earlier, when armed police pulled him from his home and jailed him in Kenya’s Kamĩtĩ Maximum Security Prison, one of the largest in Africa. There, he lives in a prison block with eighteen other political prisoners, quarantined from the general prison population.

In a conscious effort to fight back the humiliation and the intended degradation of the spirit, Ngũgĩ decides to write a novel on toilet paper, the only paper to which he has access, a book that will become his classic, Devil on the Cross.

Written in the early 1980s and never before published in America, Wrestling with the Devil is Ngũgĩ’s account of the drama and the challenges of writing the novel under twenty-four-hour surveillance. He captures not only the excruciating pain that comes from being cut off from his wife and children, but also the spirit of defiance that defines hope. Ultimately, Wrestling with the Devil is a testimony to the power of imagination to help humans break free of confinement, which is truly the story of all art.

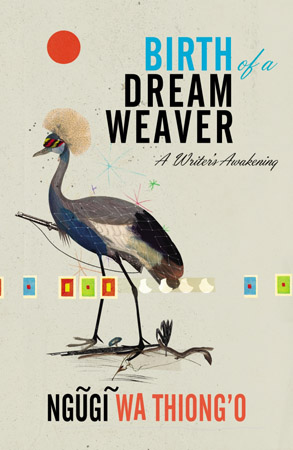

Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer’s Awakening

Memoir, 2018

“Exquisite in its honesty and truth and resilience, and a necessary chronicle from one of the greatest writers of our time. ” —Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Birth of a Dream Weaver charts the very beginnings of a writer’s creative output. In this wonderful memoir, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o recounts the four years he spent at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda—threshold years during which he found his voice as a journalist, short story writer, playwright, and novelist just as colonial empires were crumbling and new nations were being born—under the shadow of the rivalries, intrigues, and assassinations of the Cold War.

Haunted by the memories of the carnage and mass incarceration carried out by the British colonial-settler state in his native Kenya but inspired by the titanic struggle against it, Ngũgĩ, then known as James Ngugi, begins to weave stories from the fibers of memory, history, and a shockingly vibrant and turbulent present.

What unfolds in this moving and thought-provoking memoir is simultaneously the birth of one of the most important living writers—lauded for his “epic imagination” (Los Angeles Times)—the death of one of the most violent episodes in global history, and the emergence of new histories and nations with uncertain futures.

In the House of the Interpreter

Memoir, 2012

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was a student at a prestigious, British-run boarding school near Nairobi when the tumultuous Mau Mau Uprising for independence and Kenyan sovereignty gripped his country. While he enjoyed scouting trips and chess tournaments, his family home was razed to the ground and his brother, a member of the insurgency, was captured by the British and taken to a concentration camp. But Ngũgĩ could not escape history, and eventually found himself jailed after a run in with the forces of colonialism.

Ngũgĩ richly and poignantly evokes the experiences that would transform him into a world-class writer and, as a political dissident, a moral compass to us all. A winning celebration of the implacable determination of youth and the power of hope, here is a searing account of the history of a man—and the story of a nation

Dreams in a Time of War

Memoir, 2010

Born in 1938 in rural Kenya, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o came of age in the shadow of World War II, amidst the terrible bloodshed in the war between the Mau Mau and the British. The son of a man whose four wives bore him more than a score of children, young Ngũgĩ displayed what was then considered a bizarre thirst for learning, yet it was unimaginable that he would grow up to become a world-renowned novelist, playwright, and critic.

In Dreams in a Time of War, Ngũgĩ deftly etches a bygone era, bearing witness to the social and political vicissitudes of life under colonialism and war. Speaking to the human right to dream even in the worst of times, this rich memoir of an African childhood abounds in delicate and powerful subtleties and complexities that are movingly told.

Wizard of the Crow

Novel, 2006

A landmark of postcolonial African literature, Wizard of the Crow is an ambitious, magisterial, comic novel set in the fictional Free Republic of Aburiria. Ngũgĩ dramatizes with corrosive humor and keenness of observation a battle for the souls of the Aburirian people, between a megalomaniac dictator and an unemployed young man who embraces the mantle of a magician. Fashioning the stories of the powerful and the ordinary into a dazzling mosaic, in this magnificent work of magical realism, Ngũgĩ reveals humanity in all its endlessly surprising complexity.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• A Kenyan Writer and Dissident on His Year in Prison – New York Times

• The master story teller who decolonised our minds – The Hindu

• Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: ‘Resistance is the best way of keeping alive’ – The Washington Post

• An Interview with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – LA Review of Books

• Never Write In The Language of the Colonizer – TT Book

• Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, The Art of Fiction No. 253 – The Paris Review

• Prison Left Me Laughing: A Conversation with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – LA Review of Books

Listen to Audio

• Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong’o Says Prison Formed Him As A Writer – NPR

Selected Writings

Dreams in a Time of War (memoir excerpt)

Years later when I read T. S. Eliot’s line that April was the cruelest month, I would recall what happened to me one April day 1954, in chilly Limuru, the prime estate of what, in 1902, another Eliot, Sir Charles Eliot, then governor of colonial Kenya, had set aside as White Highlands. The day came back to me, the now of it, vividly.

I had not had lunch that day, and my tummy had forgotten the porridge I had gobbled that morning before the six-mile run to Kinyogori Intermediate School. Now there were the same miles to cross on my way back home; I tried not to look too far ahead to a morsel that night. My mother was pretty good at conjuring up a meal a day, but when one is hungry, it is better to find something, anything, to take one’s mind away from thoughts of food. It was what I often did at lunchtime when other kids took out the food they had brought and those who dwelt in the neighborhood went home to eat during the midday break. I would often pretend that I was going someplace, but really it was to any shade of a tree or cover of a bush, far from the other kids, just to read a book, any book, not that there were many of them, but even class notes were a welcome distraction. That day I read from the abridged version of Dickens’s Oliver Twist. There was a line drawing of Oliver Twist, a bowl in hand, looking up to a towering figure, with the caption “Please sir, can I have some more?” I identified with that question; only for me it was often directed at my mother, my sole benefactor, who always gave more whenever she could.

Listening to stories and anecdotes from the other kids was also a soothing distraction, especially during the walk back home, a lesser ordeal than in the morning when we had to run barefoot to school, all the way, sweat streaming down our cheeks, to avoid tardiness and the inevitable lashes on our open palms. On the way home, except for those kids from Ndeiya or Ngeca who had to cover ten miles or more, the walk was more leisurely. It was actually better so, killing time on the road before the evening meal of uncertain regularity or chores in and around the home compound.

Kenneth, my classmate, and I used to be quite good at killing time, especially as we climbed the last hill before home. Facing the sloping side, we each would kick a “ball,” mostly Sodom apples, backward above our heads up the hill. The next kick would be from where the first ball had landed, and so on, competing to beat each other to the top. It was not the easiest or fastest way of getting there, but it had the virtue of making us forget the world. But now we were too big for that kind of play. Besides, no games could beat storytelling for capturing our attention.

We often crowded around whoever was telling a tale, and those who were really good at it became heroes of the moment. Sometimes, in competing for proximity to the narrator, one group would push him off the main path to one side; the other group would shove him back to the other side, the entire lot zigzagging along like sheep.

This evening was no different, except for the route we took. From Kinyogori to my home village, Kwangugi or Ngamba, and its neighborhoods we normally took a path that went through a series of ridges and valleys, but when listening to a tale, one did not notice the ridge and fields of corn, potatoes, peas, and beans, each field bounded by wattle trees or hedges of kei apple and gray thorny bushes. The path eventually led to the Kihingo area, past my old elementary school, Manguo, down the valley, and then up a hill of grass and black wattle trees. But today, following, like sheep, the lead teller of tales, we took another route, slightly longer, along the fence of the Limuru Bata Shoe factory, past its stinking dump site of rubber debris and rotting hides and skins, to a junction of railway tracks and roads, one of which led to the marketplace. At the crossroads was a crowd of men and women, probably coming from market, in animated discussion. The crowd grew larger as workers from the shoe factory also stopped and joined in. One or two boys recognized some relatives in the crowd. I followed them, to listen.

“He was caught red-handed,” some were saying.

“Imagine, bullets in his hands. In broad daylight.”

Everybody, even we children, knew that for an African to be caught with bullets or empty shells was treason; he would be dubbed a terrorist, and his hanging by the rope was the only outcome.

“We could hear gunfire,” some were saying.

“I saw them shoot at him with my own eyes.”

“But he didn’t die!”

“Die? Hmm! Bullets flew at those who were shooting.”

“No, he flew into the sky and disappeared in the clouds.”

Disagreements among the storytellers broke the crowd into smaller groups of threes, fours, and fives around a narrator with his own perspective on what had taken place that afternoon. I found myself moving from one group to another, gleaning bits here and there. Gradually I pieced together strands of the story, and a narrative of what bound the crowd emerged, a riveting tale about a nameless man who had been arrested near the Indian shops.

The shops were built on the ridge, rows of buildings that faced each other, making for a huge rectangular enclosure for carriages and shoppers, with entrance-exits at the corners. The ridge sloped down to a plain where stood African-owned buildings, again built to form a similar rectangle, the enclosed space often used as a market on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The goats and sheep for sale on the same two market days were tethered in groups in the large sloping space between the two sets of shopping centers. That area had apparently been the theater of action that now animated the group of narrators and listeners. They all agreed that after handcuffing the man, the police put him in the back of their truck.

Suddenly, the man had jumped out and run. Caught unawares, the police turned the truck around and chased the man, their guns aimed at him. Some of them jumped out and pursued him on foot. He mingled with shoppers and then ran through a gap between two shops into the open space between the Indian and African shops. Here, the police opened fire. The man would fall, but only to rise again and run from side to side. Time and again this had happened, ending only with the man’s zigzagging his way through the herds of sheep and goats, down the slopes, past the African shops, across the rails, to the other side, past the crowded workers’ quarters of the Limuru Bata Shoe Company, up the ridge till he disappeared, apparently unharmed, into the European-owned lush green tea plantations. The chase had turned the hunted, a man without a name, into an instant legend, inspiring numerous tales of heroism and magic among those who had witnessed the event and others who had received the story secondhand.

I had heard similar stories about Mau Mau guerrilla fighters, Dedan Kimathi in particular; only, until then, the magic had happened far away in Nyandarwa and the Mount Kenya mountains, and the tales were never told by anybody who had been an eyewitness. Even my friend Ngandi, the most informed teller of tales, never said that he had actually seen any of the actions he described so graphically. I love listening more than telling, but this was the one story I was eager to tell, before or after the meal. Next time I met Ngandi, I could maybe hold my own.

The X-shaped barriers to the railway crossing level were raised. A siren sounded, and the train passed by, a reminder to the crowd that they still had miles to go. Kenneth and I followed suit, and when no longer in the company of the other students he spoiled the mood by contesting the veracity of the story, at least the manner in which it had been told. Kenneth liked a clear line between fact and fiction; he did not relish the two mixed. Near his place, we parted without having agreed on the degree of exaggeration.

Home at last, to my mother, Wanjiku, and my younger brother, Njinju, my sister Njoki, and my elder brother’s wife, Charity. They were huddled together around the fireside. Despite Kenneth, I was still giddy with the story of the man without a name, like one of those characters in books. Sudden pangs of hunger brought me back to earth. But it was past dusk, and that meant an evening meal might soon be served.

Food was ready all right, handed to me in a calabash bowl, in total silence. Even my younger brother, who liked to call out my failings, such as my coming home after dusk, was quiet. I wanted to explain why I was late, but first I had to quell the rumbling in my tummy.

In the end, my explanation was not necessary. My mother broke the silence. Wallace Mwangi, my elder brother, Good Wallace as he was popularly known, had earlier that afternoon narrowly escaped death. We pray for his safety in the mountains. It is this war, she said.