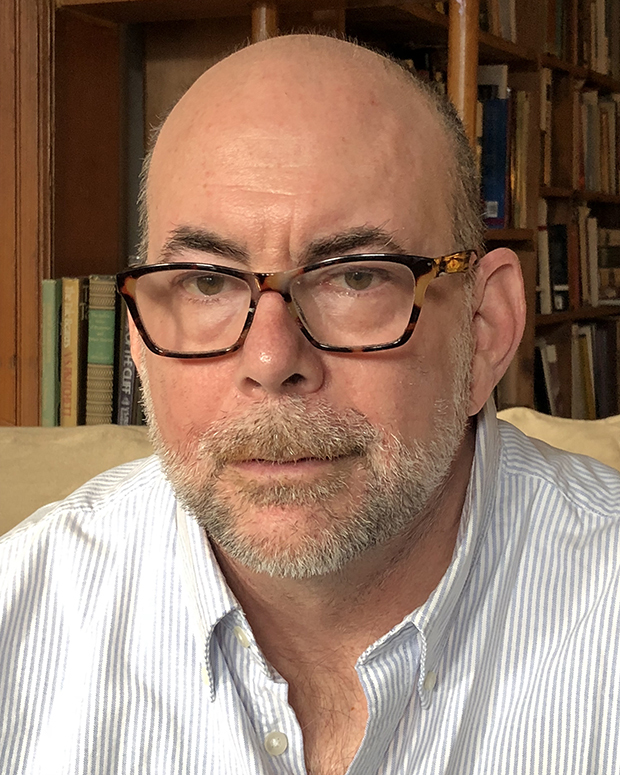

Donald Antrim

Acclaimed Memoirist & Novelist

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Donald Antrim

Biography

“No one writes more eloquently about the male crack-up and the depths of loneliness than Donald Antrim; his stories that hopscotch between the surreal and ordinary, comic and heartbreaking, are dazzling.” –Vanity Fair

“Donald Antrim’s stories are often lovely and drastic in the same breath, which becomes electrifying for the reader.” ―Richard Ford

“Antrim exhibits an elastic command of voice and a precise emotional awareness.” –The New Yorker

Donald Antrim is the critically acclaimed author of six books, including Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World (Picador, 2012);The Hundred Brothers (Picador, 2011); The Verificationist (Picador, 2011), which was a New York Times Book Review Notable Book of the Year; and The Afterlife (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007), a memoir about his mother.

Antrim’s work has been praised by his significant contemporaries, including Jonathan Franzen, Thomas Pynchon, Jeffrey Eugenides, and George Saunders, who described The Verificationist as “one of the most pleasure-giving, funny, perverse, complicated, addictive novels of the last twenty years.” Francine Prose writes of his first memoir, “The Afterlife is like nothing else. With tenderness, humor, and insight, Donald Antrim evokes the volatile atmosphere of the home that he and his sister shared with mother Louanne. This book should be required reading for everyone who has been haunted by the restless ghosts of those they love most.”

His most recent memoir, One Friday in April (W. W. Norton, 2021), is a searing and brave memoir that offers a new understanding of suicide as a distinct mental illness. In this moving memoir, Antrim vividly recounts what led him to the roof and what happened after he came back down: two hospitalizations, weeks of fruitless clinical trials, the terror of submitting to ECT—and the saving call from David Foster Wallace that convinced him to try it—as well as years of fitful recovery and setback. One Friday in April reframes suicide—whether in thought or action—as an illness in its own right, a unique consequence of trauma and personal isolation, rather than the choice of a depressed person.

A regular contributor to The New Yorker, Antrim has also been the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Grant and fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York Public Library, among others.

He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Short Bio

Donald Antrim is the critically acclaimed author of six books, including Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World, The Hundred Brothers, The Verificationist, and The Afterlife. His most recent memoir, One Friday in April (W. W. Norton, 2021), is a searing and brave memoir that offers a new understanding of suicide as a distinct mental illness. A regular contributor to The New Yorker, Antrim has also been the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Grant and fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York Public Library, among others. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Videos

Publications

One Friday in April

Memoir, 2021

A searing and brave memoir that offers a new understanding of suicide as a distinct mental illness. As the sun lowered in the sky one Friday afternoon in April 2006, acclaimed author Donald Antrim found himself on the roof of his Brooklyn apartment building, afraid for his life. In this moving memoir, Antrim vividly recounts what led him to the roof and what happened after he came back down: two hospitalizations, weeks of fruitless clinical trials, the terror of submitting to ECT—and the saving call from David Foster Wallace that convinced him to try it—as well as years of fitful recovery and setback. One Friday in April reframes suicide—whether in thought or action—as an illness in its own right, a unique consequence of trauma and personal isolation, rather than the choice of a depressed person. A necessary companion to William Styron’s classic Darkness Visible, this profound, insightful work sheds light on the tragedy and mystery of suicide, offering solace that may save lives.

The Emerald Light in the Air

Short Story, 2014

A masterful story collection-heartbreaking and hilarious-from one of America’s greatest writers. Nothing is simple for the men and women in Donald Antrim’s stories. As they do the things we all do-bum a cigarette at a party, stroll with a girlfriend down Madison Avenue, take a kid to the zoo-they’re confronted with their own uncooperative selves. These artists, writers, lawyers, teachers, and actors make fools of themselves, spiral out of control, have delusions of grandeur, despair, and find it hard to imagine a future. They talk, they listen, they hope, they dream. They look for communion in a city, both beautiful and menacing, which can promise so much and yield so little. But they are hungry for life. They want to love and be loved. These stories, all published in The New Yorker over the last fifteen years, make it clear that Antrim is one of America’s most important writers. The Emerald Light in the Air is Antrim’s best book yet: the story collection that reveals him as a master of the form.

Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World

Fiction, 2012

“A dark, suburban fantasy. Richly funny, even whimsical, and bizarrely familiar.” ―The New Yorker

In the seaside community of Donald Antrim’s Elect Mr. Robinson for a Better World, the citizens are restless. The mayor has fired stinger missiles into the Botanical Garden reflecting pool, and his public execution was a messy affair. As these hawkish suburbanites fortify their houses with deadly moats and land mines, a former third-grade teacher named Pete Robinson steps forward with a tenuous bid to replace the mayor. But can anyone satisfy the terrible will of the people? By turns funny and phantasmagorical, fiercely intelligent and imaginative, Donald Antrim’s story of suburban civics turned macabre is a new American classic.

The Hundred Brothers

Fiction, 2011

There’s Rob, Bob, Tom, Paul, Ralph, and Noah; Nick, Dennis, Bertram, Russell, and Virgil. The doctor, the documentary filmmaker, and the sculptor in burning steal; the eldest, the youngest, and the celebrated “perfect” brother, Benedict. In Donald Antrim’s mordantly funny novel The Hundred Brothers, our narrator and his colossal fraternity of ninety-eight brothers (one couldn’t make it) have assembled in the crumbling library of their family’s estate for a little sinister fun. Executed with the invention and intelligence of Barthelme and Pynchon, Antrim’s taxonomy of male specimens is in equal proportions disturbing and absurdly hilarious.

The Verificationist

Fiction, 2011

It is early spring, and Tom has called together his fellow psychologists at the Krakower Institute for their biannual pancake supper―a chance for likeminded analysts to talk shop and casually unburden themselves over flapjacks. But, as Tom knows (at least subconsciously), his brainy colleagues are a little on edge―simmering with romantic tension and professional grievance, their stew of conflicting ego and id just might boil to the surface before the pretty waitress brings their next coffee refill. When Tom tries to provoke a food fight, a rival colleague locks him in a therapeutic hold, triggering a transcendent if totally bizarre transformation that will free Tom to confront his greatest pleasures and fears. Darkly funny and beautifully written, The Verificationist confirms Donald Antrim as one of America’s best and most original authors.

The Afterlife

Memoir, 2007

In the winter of 2000, shortly after his mother’s death, Donald Antrim began writing about his family. In pieces that appeared in The New Yorker and were anthologized in Best American Essays, Antrim explored his intense and complicated relationships with his mother, Louanne, an artist, teacher, and ferociously destabilizing alcoholic; his gentle grandfather, who lived in the mountains of North Carolina and who always hoped to save his daughter from herself; and his father, who married his mother twice. The Afterlife is an elliptical, sometimes tender, sometimes blackly hilarious portrait of a family–faulty, cracked, enraging–and of a man struggling to learn the nature of his origins.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• The Best Books of 2021 – Vulture

• 9 New Books We Recommend This Week – NY Times

• Woes Make the Man: Donald Antrim’s surreal existential triptych – Bookforum

• Donald Antrim and the Art of Anxiety – New York Times

• Review of The Emerald Light in the Air by Donald Antrim – The Guardian

• Lost in Their Own Lives: A Review of The Emerald Light in the Air – New York Times

• Private Myths of the Bourgeoisie – Los Angeles Reivew of Books

Listen to Audio

Selected Writings

• How Music Can Bring Relief During These Anxious Times – The New Yorker

• Everywhere and Nowhere: A Journey Through Suicide – The New Yorker

THE EMERALD LIGHT IN THE AIR (an excerpt)

In less than a year, he’d lost his mother, his father, and, as he’d once and sometimes still felt Julia to be, the love of his life; and, during this year, or, he should say, during its suicidal aftermath, he’d twice admitted himself to the psychiatric ward at the University Hospital in Charlottesville, where, each stay, one in the fall and one the following summer, three mornings a week, Monday, Wednesday, Friday, he’d climbed onto an operating table and wept at the ceiling while doctors set the pulse, stuck electrodes to his forehead, put the oxygen meter on his finger, and then pushed a needle into his arm and instructed him, as the machines beeped and the anesthetic dripped down the pipette toward his vein, to count backward from a hundred; and now, another year later, he was on his way to the dump to throw out the drawings and paintings that Julia had made in the months when she was sneaking off to sleep with the man she finally left him to marry, along with the comic-book collection—it wasn’t a collection so much as a big box stuffed with comics—that he’d kept since he was a boy. He had long ago forgotten his old comics; and then, a few days before, he’d come across them on a dusty shelf at the back of the garage, while looking for a carton of ammo.

It was a humid Saturday morning. Thunderstorms had come through in the early hours after dawn, but now the rain and wind had passed, and sunlight lit the puddles on the road and the silver roofs of the farmhouses and barns that flickered into view between the trees, as he steered the ancient blue Mercedes—it had been his father’s, and his grandfather’s before that—across the county he’d grown up in. Maybe on his way back home he’d stop at Fox Run Farm for a gallon of raw milk. Or no. He’d drink a glass or two and then, in a month, have to dig the rest out of the refrigerator and pitch it. He reminded himself to vacuum the living room and clean the downstairs toilet. His name was Billy French, and he was carrying a Browning .30-06 A-bolt hunting rifle in the trunk of the Mercedes. He wasn’t a gun nut, and he didn’t hunt. He was a sculptor and a middle-school art teacher. Every now and then, he liked to stop on his way home from school and shoot cans off the rotting fence posts that surrounded the unused cow pasture where, at sixteen, in the grass and weeds, he’d lost his virginity to Mary Doan. He hadn’t thought about Mary in ages, and then, recently, he’d run into her—surprise, surprise, after all these years—at a bar in the Valley. He’d recognized her right away—he remembered her limp—but it had taken her a couple of tries to remember his name. They’d had a laugh over that, and he’d bought her a drink, and she’d bought him one, and now she was coming across the mountain, she was coming that night for dinner.

He’d told her seven-thirty.

Ahead on the road, a tree limb was down. He was on a small rural route, a cut between two lanes, not much used. He stopped the Mercedes, unbuckled his seat belt, and got out. A locust bough had sheared off in the wind. The bough was long and twisting, green with crooked branches and smaller, thorny stems. His tree saw and his axe were back at the house, but it might be possible to drag the bough from the tip and more or less swing the whole thing—swing wasn’t the right word, maybe—over and around and off the road, enough at least for the car to pass. He reached through the leaves and grabbed a narrow stem that stuck up in the air. There were no flowers—it was late in the season for that—but the locust’s seedpods had begun to sprout, and many of these were scattered across the asphalt.

He swatted a mosquito and got the branch in both hands. The wood was damp, and the end of the bough flexed and bent when he pulled. He moved down to a thicker part, planted his feet, and leaned back. After four or five difficult heave-hos, he’d opened enough clearance, he thought, to steer the car through. He was out of breath and his shirt was wet and sticky. He got in the driver’s seat and eased the Mercedes onto the oncoming side of the road. The ground sloped down from the road’s edge and the soil had taken on rain. As he was working his way around the branch, wheels partly on the shoulder, the car tipped to the left and then shifted further, and a piece of ground seemed to fall away underneath. It was startling: a little slide and the Mercedes plunged. Then the tires dug in, and, abruptly, a distance off the road and at a steep angle, the car settled and stopped. Billy pushed his foot against the brake. He gripped the steering wheel. When he took his hands off, he saw that he’d scraped his palms on the locust. He was bleeding.

“Shit, fuck. Shit,” he said aloud.

He turned off the engine. He hadn’t slept the night before. It wasn’t the thunder and lightning that had kept him up—he’d been going through the art works that Julia had left rolled in tubes or stacked against the wall in the upstairs bedroom that had been her studio. They were piled in the back seat now. The paintings, he thought, while sitting in the car perched on the berm, were not as strong as the drawings, which, though more or less precise studies for their oil counterparts, all rural Virginia scenes—trees in a field, a dying pond, a rotting house in a mountain hollow—nonetheless had about them, with their bold erasures and smudges and retraced pencil lines, the feeling of something abstract and, in comparison with the worked and reworked paintings, complexly three-dimensional. The paintings seemed to exist as strangely flat fields—they put Billy in mind of Early American naïve art—and, in looking at them and, back in the day, talking to Julia about them, he’d come to see how purposefully she distorted light and shadow. “I’m searching for something that isn’t quite there,” she’d once said.

He was fearful of shifting his weight and starting another slide—the car had gone four or five feet already, and the embankment fell maybe ten more. He could hear running water. Was there a creek off in the woods? He knew this country, or thought he did, but it was always surprising him, just the same.

He wiped his hands on his pants. Gently now, he ratcheted down the brake. He eased open the driver’s-side door.

Anyway, her drawings and paintings—he knew better than to throw them out, but the fact of them in his house was terrible. He’d meant for some time to do something about them. At first, of course, he’d tried to get them back to her, but she’d told him—this was during one of their five or six phone conversations since her departure, two years earlier—that her old work was no longer meaningful or important to her. “I’m not doing that kind of painting anymore,” she’d said. “I’m engaged with a more total realism.”

“Photo-realism?” he’d asked.

“No, nothing like that.”

He was standing in the kitchen in his socks and underwear, drinking bourbon and Coke—his mother’s drink. Ice rattled in the glass. The floor was brown and dirty, in need of mopping.

Julia said, “Billy, you’re drinking.”

Oh, God, how to get out of the Mercedes safely? The hillside was steep and the grass was wet. And what if he made it, with both feet firmly on the ground, and the car slid down on top of him?