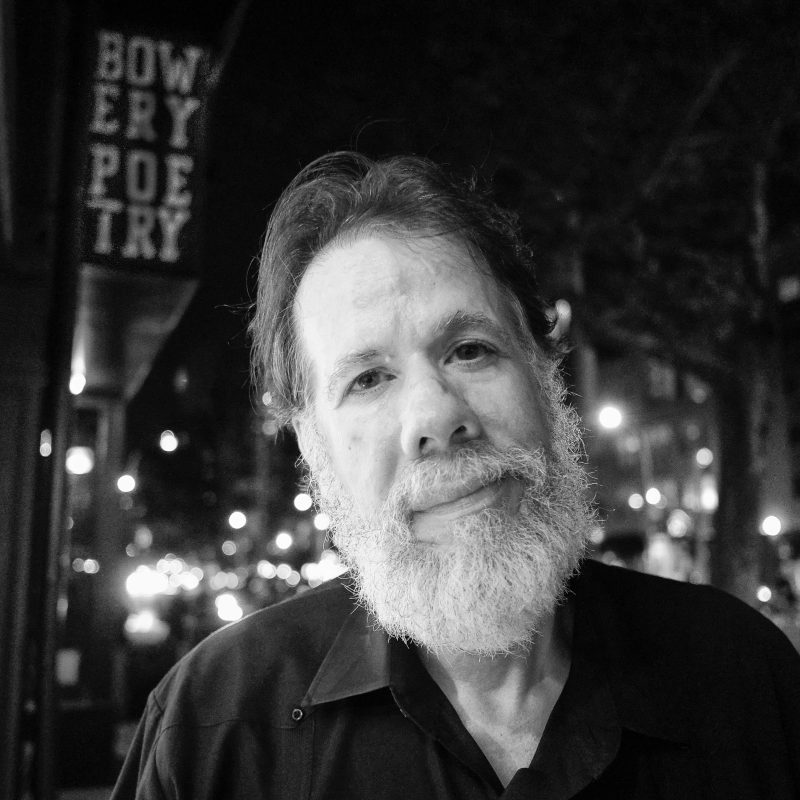

Martín Espada

National Book Award Winner

Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize

Activist

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- Humanize the Dehumanized: A Workshop on Immigration and Poetry

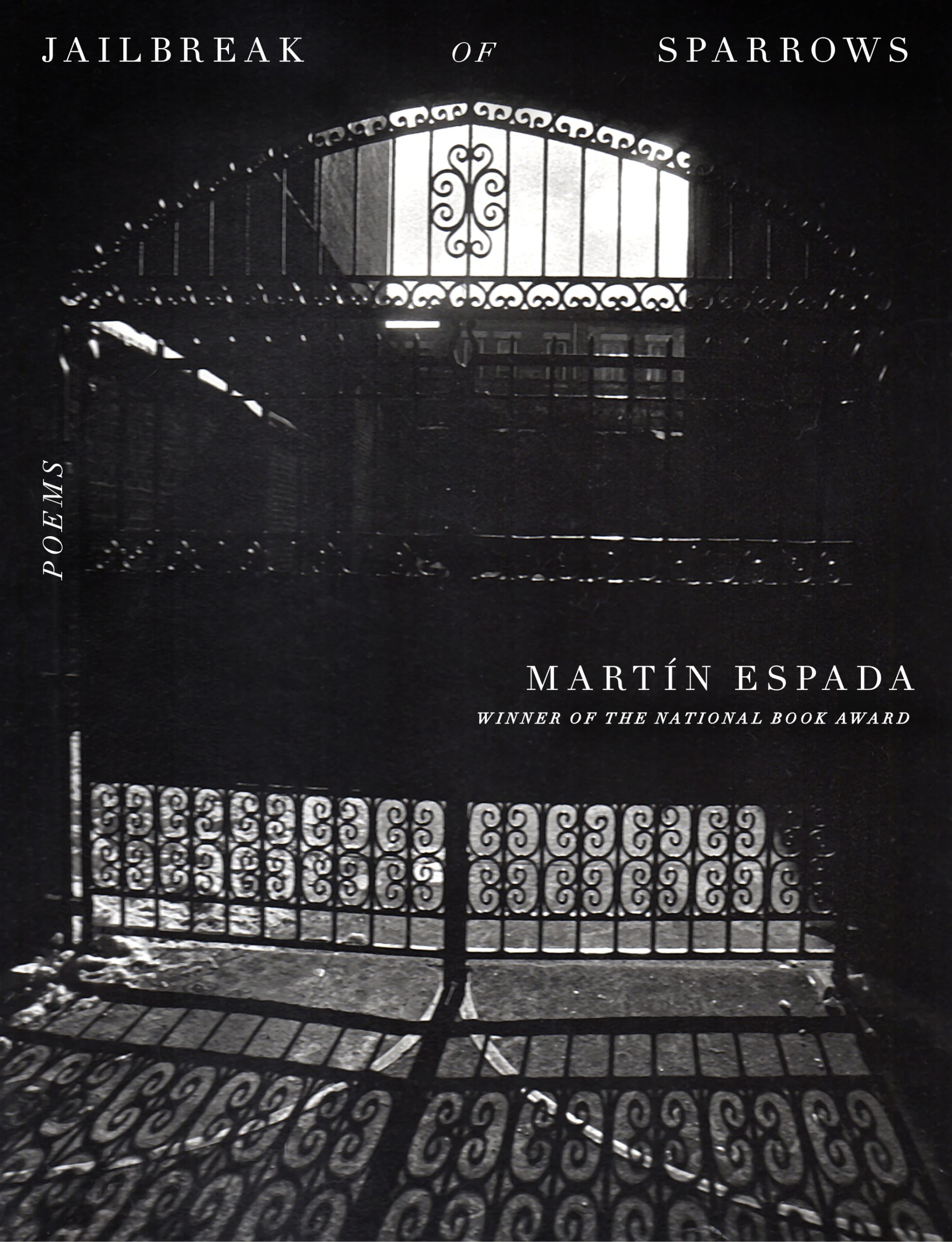

- Jailbreak of Sparrows

- Poetry of the Political Imagination

- The Lover of a Subversive is Also a Subversive: Colonialism & the Poetry of Rebellion in Puerto Rico

- My Last Name/El Apellido: A Workshop

- Who Burns for the Perfection of Paper: A Screening & Discussion

- An Evening with Martín Espada

Biography

“I want to write like Martín Espada. His poems are flowers for the ‘rabble-rousers and hell-raisers, strikers / and muckrakers, poets and socialists,’ testimonies to his allegiance to those society ignores. He is the poet laureate of the forgotten.” —Sandra Cisneros

“Martín Espada is a captivating storyteller and memoirist. His great subject is the drama of the Puerto Rican diaspora; his method is meticulously crafted portraiture of lives that intertwine with history, among them his own, radiantly defiant and fearless. One of our most important contemporary poets.” —Joyce Carol Oates

Martín Espada has published more than twenty books as a poet, editor, essayist, and translator. His latest book of poems, Jailbreak of Sparrows, was published with Knopf in April 2025. His previous book, Floaters (W.W. Norton, 2021), won the National Book Award for Poetry and a Massachusetts Book Award. His poetry collections from Norton include Vivas to Those Who Have Failed (2016), The Trouble Ball (2011), The Republic of Poetry (2006), Alabanza: New and Selected Poems (2003), A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen (2000), Imagine the Angels of Bread (1996), and City of Coughing and Dead Radiators (1993).

Of Jailbreak of Sparrows, Ilya Kaminsky observes: “Martín Espada’s beautiful, inconsolable, tender, and unrelenting poems of protest and testimony offer us a landscape where song bears witness and witness becomes a chant, which is to say: a state of being. A lyric narrative in Espada’s hands has long become a kind of healing ceremony of the ancients, a shield against the onslaught of the world’s sharper edges. Espada is a brilliant practitioner of this art.” Of Floaters, Cyrus Cassells writes: “Martín Espada is a fierce activist in verse, decrying, with accuracy and urgency, the depravity of inhumane detention and acute bigotry. One of America’s most indelible voices, as always, Espada’s poetry is lionhearted.”

He is the editor of groundbreaking anthologies such as El Coro (University of Massachusetts Press, 1997) and Poetry Like Bread: Poets of the Political Imagination (Curbstone Press, 1994). Espada also edited What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump (2019) and His Hands Were Gentle: Selected Lyrics of Víctor Jara (Smokestack, UK, 2012).

Espada often cites the influence of his father, Frank Espada, a community organizer, photographer, and creator of the Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, saying: “I grew up in my father’s household. Resistance was as natural as breathing. I was surprised when I went into the world and discovered that not everybody was raised the way I was. So, when it turned to the writing of poetry, quite naturally it turned to poetry about social justice.”

There is a short film about an Espada poem produced by the Poetry in America Series for PBS, called “Who Burns for the Perfection of Paper,” featuring commentary from actor John Turturro, historian Jill Lepore, retired Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, and the poet himself.

Espada has received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Shelley Memorial Award, the Robert Creeley Award, the National Hispanic Cultural Center Literary Award, an Academy of American Poets Fellowship, the PEN/Revson Fellowship, a Letras Boricuas Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. The Republic of Poetry was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. The title poem of his collection Alabanza, about 9/11, has been widely anthologized and performed. His book of essays and poems, Zapata’s Disciple, was banned in Tucson as part of the Mexican-American Studies Program outlawed by the state of Arizona and issued in a new edition by Northwestern (2016). A former tenant lawyer with Su Clínica Legal, a bilingual legal services program in Greater Boston, Espada is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Short Bio

Martín Espada has published more than twenty books as a poet, editor, essayist, and translator. His latest book of poems Jailbreak of Sparrows was published with Knopf in 2025. His previous book, Floaters, won the National Book Award for Poetry and a Massachusetts Book Award. His poetry collections from W.W. Norton include Vivas to Those Who Have Failed (2016), The Trouble Ball (2011), The Republic of Poetry (2006), Alabanza (2003) and Imagine the Angels of Bread (1996). He is the editor of What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump (2019). Espada has received the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the Shelley Memorial Award, an Academy of American Poets Fellowship, the PEN/Revson Fellowship, a Letras Boricuas Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. The title poem of his collection Alabanza, about 9/11, has been widely anthologized and performed. His book of essays and poems, Zapata’s Disciple (1998), was banned in Tucson as part of the Mexican-American Studies Program outlawed by the state of Arizona. A former tenant lawyer, Espada is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

Jailbreak of Sparrows

Poetry, 2025

In this brilliant new collection of poems, National Book Award winner Martín Espada offers narratives of the forgotten and the unforgettable.

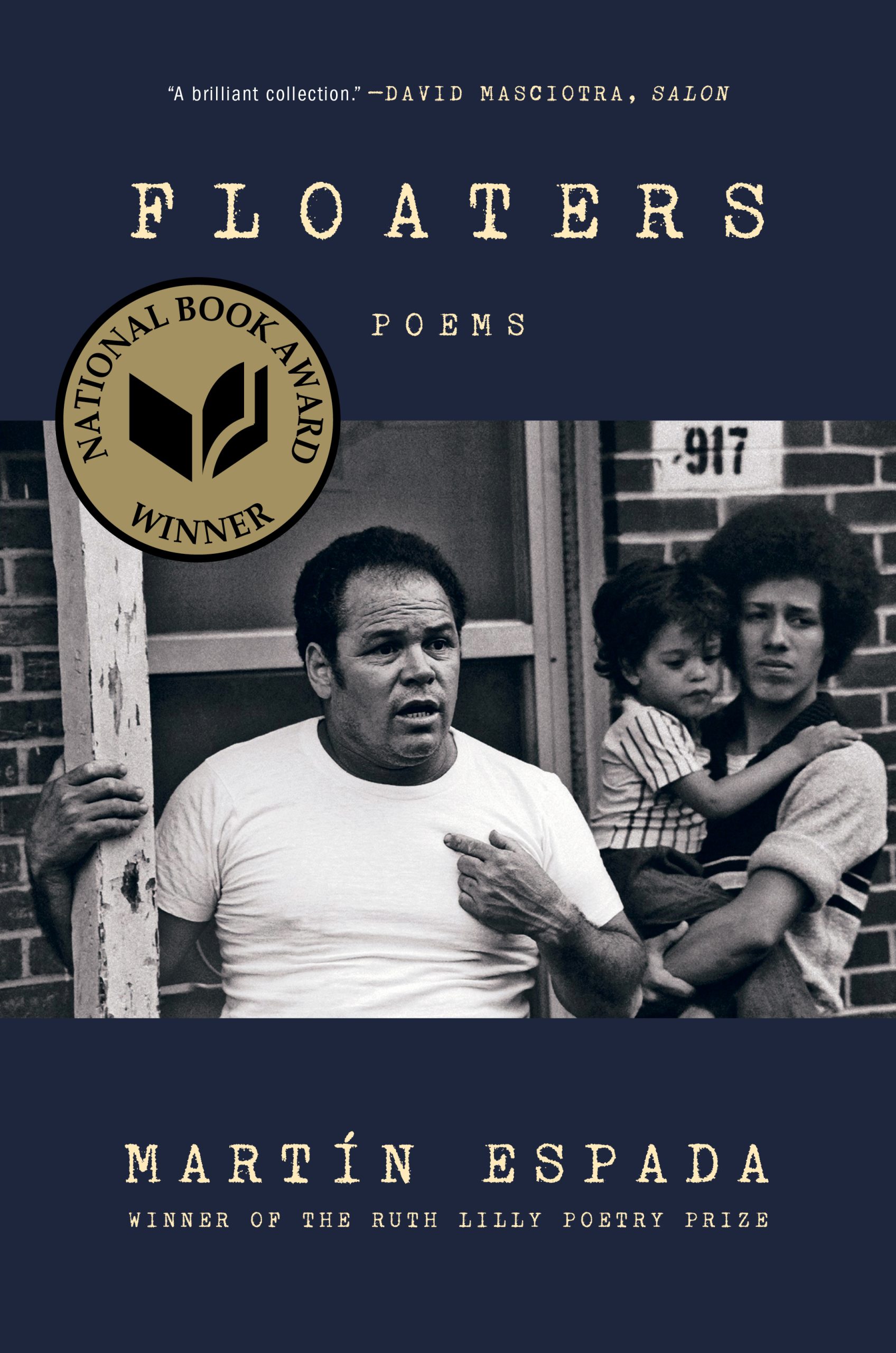

Floaters

Poetry, 2021

“Martín Espada’s Floaters manages to address the concerns of our times through a timeless voice that can be heard above ‘this cacophonous world.’ These poems remind us of the power of observation, of seeing everything…believing all are worthy of song, all are worthy of taking seriously within our song. This is a collection that is vital for our times and will be vital for those in the future, trying to make sense of today.” —Judges’ Citation, National Book Award in Poetry, 2021

From the winner of the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize come masterfully crafted narratives of protest, grief and love.

Martín Espada is a poet who “stirs in us an undeniable social consciousness,” says Richard Blanco. Floaters offers exuberant odes and defiant elegies, songs of protest and songs of love from one of the essential voices in American poetry.

Floaters takes its title from a term used by certain Border Patrol agents to describe migrants who drown trying to cross over. The title poem responds to the viral photograph of Óscar and Valeria, a Salvadoran father and daughter who drowned in the Río Grande, and allegations posted in the “I’m 10-15” Border Patrol Facebook group that the photo was faked. Espada bears eloquent witness to confrontations with anti-immigrant bigotry as a tenant lawyer years ago, and now sings the praises of Central American adolescents kicking soccer balls over a barbed wire fence in an internment camp founded on that same bigotry. He also knows that times of hate call for poems of love—even in the voice of a cantankerous Galápagos tortoise.

The collection ranges from historical epic to achingly personal lyrics about growing up, the baseball that drops from the sky and smacks Espada in the eye as he contemplates a girl’s gently racist question.

Whether celebrating the visionaries—the fallen dreamers, rebels and poets—or condemning the outrageous governmental neglect of his father’s Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane María, Espada invokes ferocious, incandescent spirits.

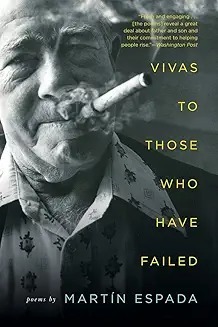

Vivas to Those Who Have Failed

Poetry, 2017

Award-winning poet Martín Espada gives voice to the spirit of endurance in the face of loss.

In this powerful collection of poems, Martín Espada articulates the transcendent vision of another, possible world. He invokes the words of Whitman in “Vivas to Those Who Have Failed,” a cycle of sonnets about the Paterson Silk Strike and the immigrant laborers who envisioned an eight-hour workday. At the heart of this volume is a series of ten poems about the death of the poet’s father. “El Moriviví” uses the metaphor of a plant that grows in Puerto Rico to celebrate the many lives of Frank Espada, community organizer, civil rights activist, and documentary photographer, from a jailhouse in Mississippi to the streets of Brooklyn. The son lyrically imagines his father’s return to a bay in Puerto Rico: “May the water glow blue as a hyacinth in your hands.” Other poems confront collective grief in the wake of the killings at the Sandy Hook Elementary School and police violence against people of color: “Heal the Cracks in the Bell of the World” urges us to “melt the bullets into bells.” Yet the poet also revels in the absurd, recalling his dubious career as a Shakespearean “actor,” finding madness and tenderness in the crowd at Fenway Park. In exquisitely wrought images, Espada’s poems show us the faces of Whitman’s “numberless unknown heroes.”

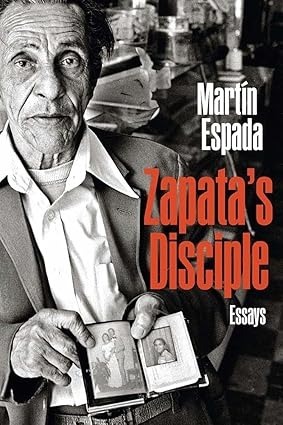

Zapata's Disciple

Essays, 2016

The ferocious acumen with which the award-winning poet Martín Espada attacks issues of social injustice in Zapata’s Disciple makes it no surprise that the book has been the subject of bans in both Arizona and Texas, targeted for its presence in the Mexican American Studies curriculum of Tucson’s schools and for its potential to incite a riot among Texas prison populations. This new edition of Zapata’s Disciple, which won the 1999 Independent Publisher Book Award for Essay/Creative Nonfiction, opens with an introduction in which the author chronicles this history of censorship and continues his lifelong fight for freedom of expression. A dozen of Espada’s poems, tender and wry as they are powerful, interweave with essays that address the denigration of the Spanish language by American cultural arbiters, castigate Nike for the exploitation of its workers, reflect upon National Public Radio’s censorship of Espada’s poem about Mumia Abu- Jamal, and more.

Zapata’s Disciple is a potent assault on the continued marginalization of Latinos and other poor and working-class citizens in American society, and the collection breathes with a revolutionary zeal that is as relevant now as when it was first published. “After all, ‘any progressive social change must be imagined first,’ and lately Espada has been doing a lot of imagination. Here he sets down not merely the basis of his convictions but their putative outcome. He has clarified an aesthetics of activism.” —American Book Review

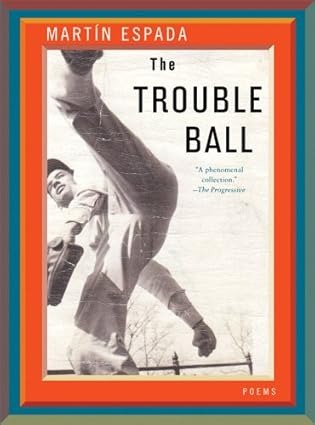

The Trouble Ball

Poetry, 2011

In this collection of poems, Martín Espada crosses the borderlands of epiphany and blasphemy: Ebbets Field, Brooklyn, in 1941, where his Puerto Rican father realizes, at the age of eleven, that dark-skinned players are not allowed on the field; the swimming pool for guards and their families at Villa Grimaldi, a center of interrogation, torture, and execution in Pinochet’s Chile; the city park where the poet clumsily buries the ashes of a friend; the tomb of Frederick Douglass, now a place of pilgrimage. Espada also traces the footsteps of his own history, from his brawls in the schoolyard to his days selling encyclopedias door-to-door. He observes the tender gestures of worlds half in shadow, where an “illegal immigrant” gazes at the snapshots of her wedding to a stranger, or a high school wrestler helps to carry an evicted neighbor’s couch back into her apartment. And he urges us to envision justice, to “bury what we call / the impossible, the unthinkable, the unimaginable, now and forever.”

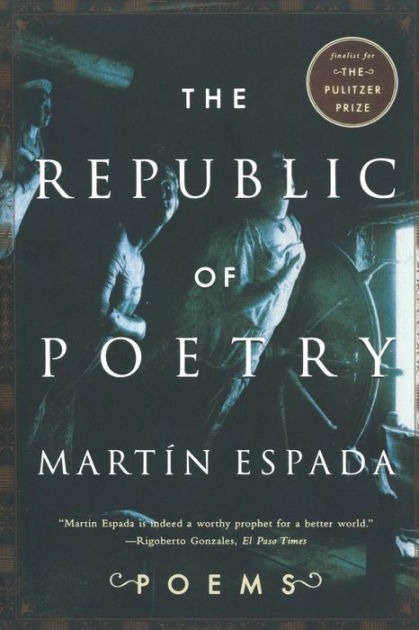

The Republic of Poetry

Poetry, 2006

In his eighth collection of poems, a finalist for the 2007 Pulitzer Prize, Martín Espada celebrates the power of poetry itself. The Republic of Poetry is a place of odes and elegies, collective memory and hidden history, miraculous happenings and redemptive justice.

Called by Sandra Cisneros “the Pablo Neruda of North American authors,” Espada traveled to Chile in July 2004 to take part in the commemoration of the Neruda centenary. The heart of the new collection is a cycle of Chile poems. This is a narrative of creation, destruction and redemption: Neruda’s house in Santiago, wrecked by the military during the coup and rehabilitated in a democratic Chile; Joan Jara walking through the stadium where her husband Víctor was executed after singing for his fellow prisoners; the young poets who rent a helicopter and “bomb” the national palace with poetry on bookmarks; the disgraced dictator Augusto Pinochet, jeered leaving a used bookstore.

The Republic of Poetry is a land where poets return from the dead. Robert Creeley shares a cigarette with Henry David Thoreau; Clemente Soto Vélez visits in a dream and urges a pilgrimage to the caves of Puerto Rico; Julia de Burgos speaks to a man in jail, who paints her face on an envelope. This is a land of miracles, where the God of the Weather-Beaten Face frees Carlos Mejía–an Iraq war veteran turned conscientious objector—-from incarceration, and Captain Ahab himself leads a rather demanding poetry workshop in Provincetown.

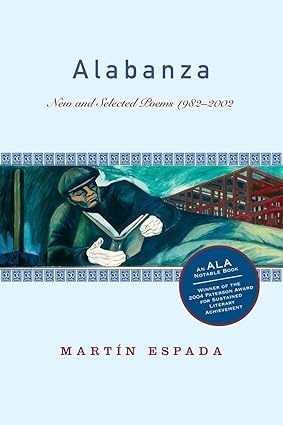

Alabanza: New and Selected Poems

Poetry, 2003

“An astonishing collection of political poetry at its finest.”—The Progressive, Favorite Books of 2004

Alabanza is a twenty-year collection charting the emergence of Martín Espada as the preeminent Latino lyric voice of his generation. “Alabanza” means “praise” in Spanish, and Espada praises the people Whitman called “them the others are down upon”: the African slaves who brought their music to Puerto Rico; a prison inmate provoking brawls so he could write poetry in solitary confinement; a janitor and his solitary strike; Espada’s own father, who was jailed in Mississippi for refusing to go to the back of the bus. The poet bears witness to death and rebirth at the ruins of a famine village in Ireland, a town plaza in México welcoming a march of Zapatista rebels, and the courtroom where he worked as a tenant lawyer. The title poem pays homage to the immigrant food-service workers who lost their lives in the attack on the World Trade Center. From the earliest out-of-print work to the seventeen new poems included here, Espada celebrates the American political imagination and the resilience of human dignity. Alabanza is the epic vision of a writer who, in the words of Russell Banks, “is one of the handful of American poets who are forging a new American language, one that tells the unwritten history of the continent, speaks truth to power, and sings songs of selves we can no longer silence.” An American Library Association Notable Book of 2003 and a 2003 New York Public Library Book to Remember.

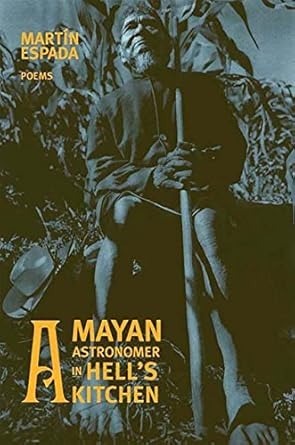

A Mayan Astronomer in Hell's Kitchen

Poetry, 2000

“Martín Espada ….forges a new poetic language.”—Dennis Loy Johnson, Pittsburgh Tribune

In his sixth collection, American Book Award-winner Martín Espada has created a poetic mural. There are conquerors, slaves, and rebels from Caribbean history; the “Mayan astronomer” calmly smoking a cigarette in the middle of a New York tenement fire; a nun staging a White House vigil to protest her torture; a man on death row mourning the loss of his books; and even Carmen Miranda.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Poetic Interventions: Martín Espada’s New Collection and the Fight Against Fascism – Counter Punch

• Martín Espada 101: A brief guide to his work. – Poetry Foundation

• Interview: “The imagination is absolutely critical to political activism” – Salon

• Sailing Over a Barbed Wire Fence – The Progressive Magazine

Listen to Audio

• Poetry Unbound interview with Pádraig Ó Tuama – On Being

• Interview on New England Public Media – NEPR

• Espada Reads “Letter to My Father” – The Poetry Magazine Podcast

Selected Writings

Letter to My Father

October 2017

You once said: My reward for this life will be a thousand pounds of dirt

shoveled in my face. You were wrong. You are seven pounds of ashes

in a box, a Puerto Rican flag wrapped around you, next to a red brick

from the house in Utuado where you were born, all crammed together

on my bookshelf. You taught me there is no God, no life after this life,

so I know you are not watching me type this letter over my shoulder.

When I was a boy, you were God. I watched from the seventh floor

of the projects as you walked down into the street to stop a public

execution. A big man caught a small man stealing his car, and everyone

in Brooklyn heard the car alarm wail of the condemned: He’s killing me.

At a word from you, the executioner’s hand slipped from the hair

of the thief. The kid was high, was all you said when you came back to us.

When I was a boy, and you were God, we flew to Puerto Rico. You said:

My grandfather was the mayor of Utuado. His name was Buenaventura.

That means good fortune. I believed in your grandfather’s name.

I heard the tree frogs chanting to each other all night. I saw banana

leaf and elephant palm sprouting from the mountain’s belly. I gnawed

the mango’s pit, and the sweet yellow hair stuck between my teeth.

I said to you: You came from another planet. How did you do it?

You said: Every morning, just before I woke up, I saw the mountains.

Every morning, I see the mountains. In Utuado, three sisters,

all in their seventies, all bedridden, all Pentecostales who only left

the house for church, lay sleeping on mattresses spread across the floor

when the hurricane gutted the mountain the way a butcher slices open

a dangled pig, and a rolling wall of mud buried them, leaving the fourth

sister to stagger into the street, screaming like an unheeded prophet

about the end of the world. In Utuado, a man who cultivated a garden

of aguacate and carambola, feeding the avocado and star fruit to his

nieces from New York, saw the trees in his garden beheaded all at once

like the soldiers of a beaten army, and so hanged himself. In Utuado,

a welder and a handyman rigged a pulley with a shopping cart to ferry

rice and beans across the river where the bridge collapsed, witnessed

the cart swaying above so many hands, then raised a sign that told

the helicopters: Campamento los Olvidados: Camp of the Forgotten.

Los olvidados wait seven hours in line for a government meal of Skittles

and Vienna sausage, or a tarp to cover the bones of a house with no roof,

as the fungus grows on their skin from sleeping on mattresses drenched

with the spit of the hurricane. They drink the brown water, waiting

for microscopic monsters in their bellies to visit plagues upon them.

A nurse says: These people are going to have an epidemic. These people

are going to die. The president flips rolls of paper towels to a crowd

at a church in Guaynabo, Zeus lobbing thunderbolts on the locked ward

of his delusions. Down the block, cousin Ricardo, Bernice’s boy, says

that somebody stole his can of diesel. I heard somebody ask you once

what Puerto Rico needed to be free. And you said: Tres pulgadas

de sangre en la calle: Three inches of blood in the street. Now, three

inches of mud flow through the streets of Utuado, and troops patrol

the town, as if guarding the vein of copper in the ground, as if a shovel

digging graves in the back yard might strike the ore below, as if la brigada

swinging machetes to clear the road might remember the last uprising.

I know you are not God. I have the proof: seven pounds of ashes in a box

on my bookshelf. Gods do not die, and yet I want you to be God again.

Stride from the crowd to seize the president’s arm before another roll

of paper towels sails away. Thunder Spanish obscenities in his face.

Banish him to a roofless rainstorm in Utuado, so he unravels, one soaked

sheet after another, till there is nothing left but his cardboard heart.

I promised myself I would stop talking to you, white box of grey grit.

You were deaf even before you died. Hear my promise now: I will take you

to the mountains, where houses lost like ships at sea rise blue and yellow

from the mud. I will open my hands. I will scatter your ashes in Utuado.

Gonzo

Everybody knew Gonzo, his cigarettes and cologne, his gold crucifix,

the white T-shirt he wore to every meeting. They leaned closer to listen

whenever he spoke in the circle at the rehab center, some with eyes shut,

seeing his confessions of addiction’s demons and sobriety’s angels at war.

No one knew Gonzo signed his name with an X. The tutor at the rehab center

held up flash cards and sounded out the letters: A, B, C. There was no alphabet

song in Gonzo’s head, no teacher at the blackboard. He said the letters, one

by one. At the letter S, he stopped. The tutor studied Gonzo’s nose, long but

not as long as the nose of the Muppet with the same name. S, she said again.

Gonzo had no front teeth, no place for his tongue to go. He puffed and sprayed,

a man unable to navigate the river of his own name: González. He hid his face

in his hands, unlettered cards in his head, as if the tutor could not see him now.

A sob surged through him, a beast chained to the rock of his ribs for fifty years,

since the days the roosters woke him up for school in Puerto Rico. He wiped his

face clean. Gonzo was clean: clean fingernails, clean-shaven, clean white shirt.

The tutor waited, thinking: He doesn’t know his letters, but he knows every

street in Paterson by name. She squeezed Gonzo’s wrist once, then again,

till his eyes met hers. She held up the next flash card. She said: Say T.