Caryl Phillips

Award-winning Novelist & Playwright

PEN/Open Book Award

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Caryl Phillips

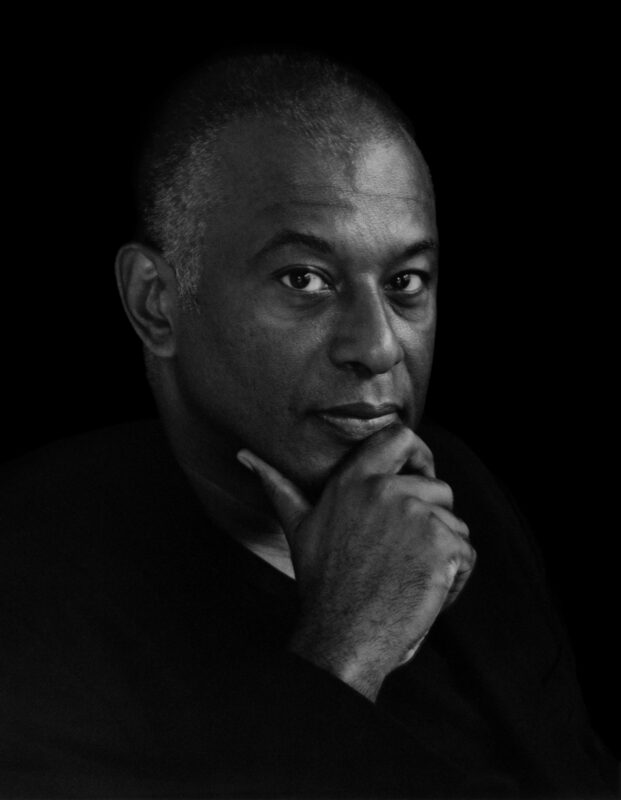

Biography

“Throughout Phillips’s fiction and nonfiction, he focuses on people who are caught in between places, desires, and circumstances of history.” —World Literature Review

“One of the literary giants of our time.” —The New York Times

Caryl Phillips was born in St. Kitts and came to Britain at the age of four months. He grew up in Leeds, and studied English Literature at Oxford University. He is the author of many novels, plays, screenplays, and works of nonfiction and his work has been translated into over a dozen languages.

Phillips began writing for the theatre and his plays include Strange Fruit (1980), Where There is Darkness (1982) and The Shelter (1983). He won the BBC Giles Cooper Award for Best Radio Play of the year with The Wasted Years (1984). Phillips has written many dramas and documentaries for radio and television, including, in 1996, the three-hour film of his own novel The Final Passage. He wrote the screenplay for the film Playing Away (1986) and his screenplay for the Merchant Ivory adaptation of V.S.Naipaul’s The Mystic Masseur (2001) won the Silver Ombu for best screenplay at the Mar Del Plata film festival in Argentina.

Phillips novels include: The Final Passage (1985), A State of Independence (1986), Higher Ground (1989), Cambridge (1991), Crossing the River (1993), The Nature of Blood (1997), A Distant Shore (2003), Dancing in the Dark (2005), Foreigners (2007), In the Falling Snow (2009), The Lost Child (2015), and A View of the Empire at Sunset (2018). In addition to his fiction, he is the author of the nonfiction titles: The European Tribe (1987), The Atlantic Sound (2000), A New World Order (2001), and Colour Me English (2011). Phillips is also the editor of two anthologies: Extravagant Strangers: A Literature of Belonging (1997) and The Right Set: An Anthology of Writing on Tennis (1999).

Phillips was named Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year in 1992 and was on the 1993 Granta list of Best of Young British Writers. His literary awards include the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a British Council Fellowship, a Lannan Foundation Fellowship, and Britain’s oldest literary award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, for Crossing the River which was also shortlisted for the 1993 Booker Prize. A Distant Shore was longlisted for the 2003 Booker Prize, and won the 2004 Commonwealth Writers Prize; Dancing in the Dark won the 2006 PEN/Open Book Award. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and the Royal Society of the Arts, and recipient of the 2013 Anthony N. Sabga Caribbean Award for Excellence.

He has taught at universities in Ghana, Sweden, Singapore, Barbados, India, and the United States, and in 1999 was the University of the West Indies Humanities Scholar of the Year. From 2002-2003 he was a Fellow at the Centre for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library. Phillips is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

Formerly Henry R. Luce Professor of Migration and Social Order at Columbia University, Phillips is presently Professor of English at Yale University and an Honorary Fellow of The Queen’s College, Oxford University.

Visit Author WebsiteVideos

Publications

A View of the Empire at Sunset

Fiction, 2018

A View of the Empire at Sunset is the sweeping story of the life of the woman who became known to the world as Jean Rhys. Born Ella Gwendolyn Rees Williams in Dominica at the height of the British Empire, Rhys lived in the Caribbean for only sixteen years before going to England. A View of the Empire at Sunset is a look into her tempestuous and unsatisfactory life in Edwardian England, 1920s Paris, and then again in London. Her dream had always been to one day return home to Dominica. In 1936, a forty-five-year-old Rhys was finally able to make the journey back to the Caribbean. Six weeks later, she boarded a ship for England, filled with hostility for her home, never to return. Phillips’s gripping new novel is equally a story about the beginning of the end of a system that had sustained Britain for two centuries but that wreaked havoc on the lives of all who lived in the shadow of the empire: both men and women, colonizer and colonized.

A true literary feat, A View of the Empire at Sunset uncovers the mysteries of the past to illuminate the predicaments of the present, getting at the heart of alienation, exile, and family by offering a look into the life of one of the greatest storytellers of the twentieth century and retelling a profound story that is singularly its own.

The Lost Child

Fiction, 2015

At the center of the novel is Monica Johnson—cut off from her parents after falling in love with a foreigner—and her bitter struggle to raise her sons in the shadow of the wild moors of the north of England. Phillips intertwines Monica’s modern narrative with the childhood of one of literature’s most enigmatic lost boys as he conjures young Heathcliff, the antihero of Wuthering Heights, and his ragged existence before Mr. Earnshaw brought him home to his family.

A true literary feat, The Lost Child recovers the mysteries of the past to illuminate the predicaments of the present, getting at the heart of alienation, exile, and family by transforming a classic into a profound story that is singularly its own.

Colour Me English

Nonfiction, 2011

Taking as its starting point a moving recollection of growing up in Leeds during the 1970s, Colour Me English broadens into a reflective, entertaining and challenging collection of essays and other non-fiction writing which ranges from the literary to the cultural and autobiographical.

Elsewhere, Caryl Phillips goes on to describe the experience of living and working in America, and travels in Sierra Leone, Ghana, Belgium and France and beyond. He considers the lives and work of figures, amongst many others, including Chinua Achebe, James Baldwin, Billie Holiday and Luther Vandross, and how their experiences are refracted through the prisms of writing, music and cinema.

But Colour Me English always circles back to questions of identity and belonging, and of its reverse, exclusion.

In the Falling Snow

Fiction, 2009

Keith—born in the 1960s to immigrant West Indian parents, raised primarily by his white stepmother—is in his forties, a social worker heading a Race Equality unit in London whose life has come undone: separated from his wife of twenty years (her family “let her go” for marrying a black man); kept at arm’s length by his seventeen-year-old son; estranged from his father; accused of harassment by a coworker. And beneath it all, a desperate feeling that his work and he himself are no longer relevant.

Moving between past and present, the narrative uncovers the particulars of class, background, temperament, and desire that have brought Keith to this moment; and reveals how, often unwittingly, his wife, his son, and his father help him grasp the breadth of the changes that have occurred around him—and what those changes will require of him.

Foreigners

Nonfiction, 2007

Francis Barber, “given” to the great eighteenth-century writer Samuel Johnson, afforded an unusual depth of freedom, which, after Johnson’s death, would help hasten his wretched demise….Randolph Turpin, Britain’s first black world champion boxer, who made history in 1951 by defeating Sugar Ray Robinson, and who ended his life in debt and despair…David Oluwale, a Nigerian stowaway who arrived in Leeds in 1949, the events of whose life called into question the reality of English justice, and whose death at the hands of police in 1969 served as a wake up call for the entire nation.

Each of these men’s stories is told in a different, perfectly realized voice. Each illuminates the complexity and drama that lie behind the simple notions of haplessness that have been used to explain the tragedy of their lives. And each explores, in entirely new ways, the themes—at once timeless and urgent—that have been at the heart of all of Caryl Phillips’ work: belonging, identity, and race.

Dancing in the Dark

Fiction, 2005

Even as an eleven-year-old child living in Southern California in the late 1800s—his family had recently emigrated from the Bahamas—Bert Williams understood that he had to “learn the role that America had set aside for him.” At the age of twenty-two, after years of struggling for success on the stage, he made the radical decision to do his own “impersonation of a negro”: he donned blackface makeup and played the “coon” as a character. Behind this mask, he became a Broadway headliner, starring in the Ziegfeld Follies for eight years and leading his own musical theater company—as influential a comedian as Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, and W. C. Fields.

Williams was a man of great intelligence, elegance, and dignity, but the barriers he broke down onstage continued to bear heavily on his personal life, and the contradictions between the man he was and the character he played were increasingly irreconcilable for him. W. C. Fields called him “the funniest man I ever saw, and the saddest man I ever knew,” and it is this dichotomy at Williams’s core that Caryl Phillips illuminates in a richly nuanced, brilliantly written narrative.

The story of a single life, Dancing in the Dark is also a novel about the tragedies of race and identity, and the perils of self-invention, that have long plagued American culture.

A New World Order

Nonfiction, 2001

A New World Order ranges widely across the Atlantic World that Caryl Phillips has charted in his award-winning novels and non-fiction books during the course of the past twenty years.

Phillips begins this distinctive collection of essays by establishing his belief that thre is a “new world order” of cultural plurality, one which is being promoted by the increasingly central role of the migrant and the refugee in the modern world. He goes on to reflect on the work of such seminal figures as Derek Walcott. V. S. Naipaul, J. M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer. But this rich harvest of essays is not simply limited to the literary: Phillips goes in search of Steven Spielberg, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Marvin Gaye. He writes about the moment when St. Kitts, the small island of his birth, became independent and talks about the role and responsibility of being a writer born into a postcolonial world who lives on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the final section of this ground-breaking collection he turns the spotlight on Britain and examines the country that formed and educated him, speculating about his parents’ migration to Britain in the late nineteen-fifties, the continuing legacy of racism, his own helpless loyalty to Leeds United, and his anxieties at feeling as though he is both of, and not of, Britain.

The Atlantic Sound

Nonfiction, 2000

Phillips initially journeys from the Caribbean to Britain by banana boat, repeating a journey he made to England as a child in the late nineteen-fifties. He then visits three pivotal cities: Liverpool, developed on the back of the slave trade, which is now in denial about the true facts of its own history; Elmina, on the west coast of Ghana, site of the most important slave fort in Africa, and now a tourist destination for African-Americans; and Charleston in the American south, celebrated as the city where the Civil War began—not for being the city where fully one-third of African-Americans were landed and sold into bondage. Finally, Phillips journeys to Israel where he encounters a community of two thousand African-Americans, whose thirty-year sojourn in the Negev desert leaves him once again contemplating the modern condition of diasporan displacement.

Crossing the River

Novel, 1995

Cambridge

Novel, 1993

One of England’s most widely acclaimed young novelists adopts two eerily convincing narrative voices and juxtaposes their stories to devastating effect in this mesmerizing portrait of slavery. Cambridge is a devoutly Christian slave in the West Indies whose sense of justice is both profound and self-destructive, while Emily is a morally-blind, genteel Englishwoman.

The European Tribe

Nonfiction, 1987

Seeking personal definition within the parameters of growing up black in Europe, he discovers that the natural loneliness and confusion inherent in long journeys collide with the bigotry of the “European Tribe”—a global community of whites caught up in an unyielding, Eurocentric history. Phillips illustrates the scenes and characters he encounters, in places like poverty-stricken Casablanca, racy Costa del Sol, and peaceful Provence, where he muses with writer James Baldwin over dinner about the state of the human spirit. He explores Venice through the Shakespearean outcast Othello and views Amsterdam through the eyes of young Anne Frank.

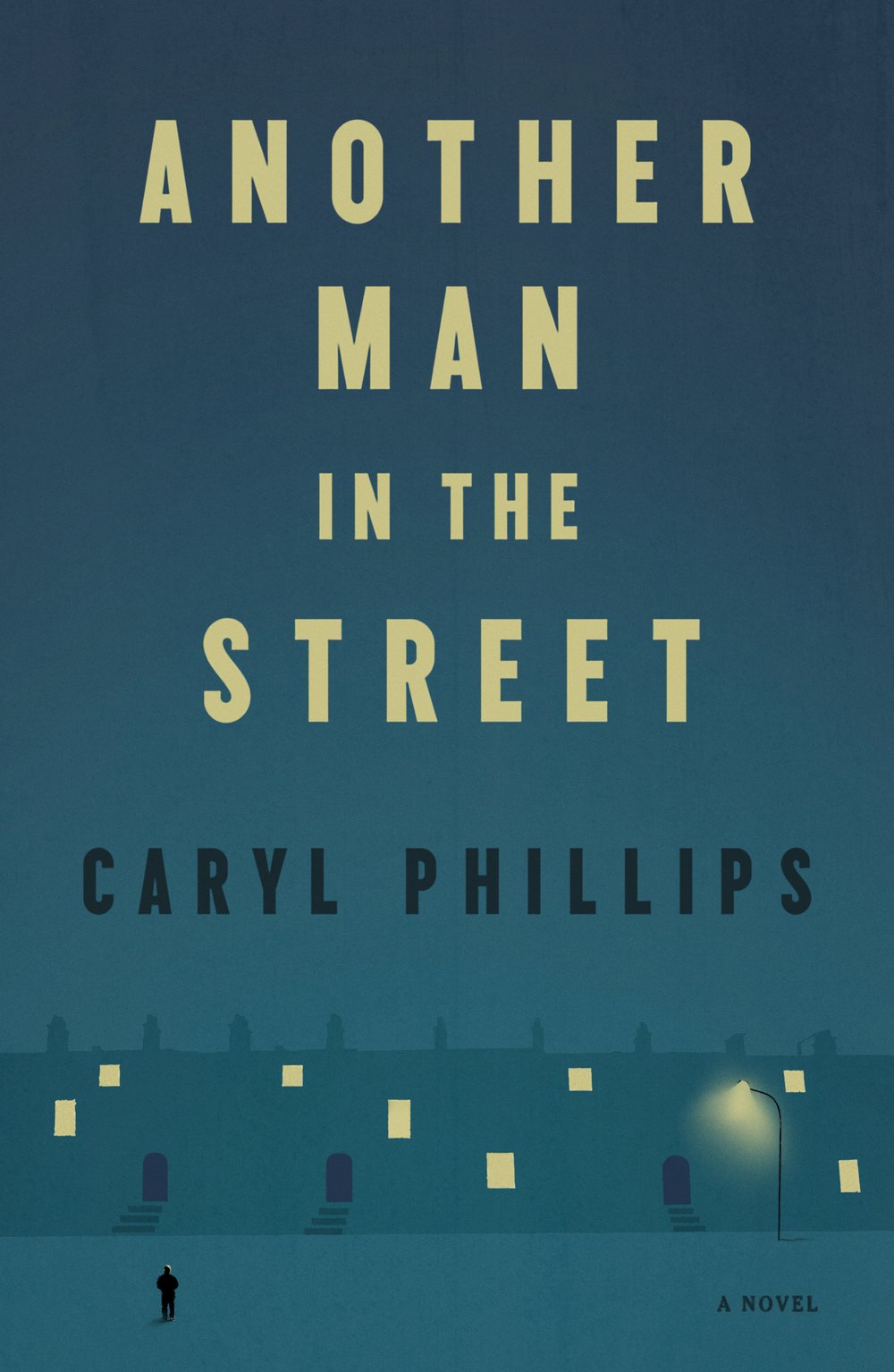

Another Man in the Street

Fiction, 2025

In London’s “swinging sixties,” Victor Johnson, a young immigrant from the Caribbean, arrives in Britain with dreams of becoming a journalist in the “mother country.” Instead, he finds work collecting rent for Peter Feldman, a landlord equally kind and unscrupulous, and then falls into a relationship with Peter’s lonely secretary Ruth, herself a migrant from the north of England. Spanning nearly half a century, and set against the backdrop of a country which is slowly, reluctantly, evolving into a modern, multiracial society, we discover the truth of both Peter’s tragic background and Ruth’s agonizing secret, and witness Victor, out of his depth, adjusting to the painful realities of life in his new country. Both epic in its sweep and devastatingly intimate in its portrayal of damaged lives all caught between two worlds, Another Man in the Street lays bare the traumas that often overtake personal relationships in the wake of transforming societies, and the high price of attempting to reinvent oneself.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• Two Writers Haunted by Their Caribbean Past – New York Times

• The Nature of Empathy: An interview with Caryl Phillips – Journal of Postcolonial Writing

• Interview with Caryl Phillips – BOMB Magazine

Listen to Audio

• Giovanni’s Room with Caryl Phillips – On the Road with Penguin Classics

• Portland Arts & Lectures: A lecture by Caryl Phillips – The Archive Project

Selected Writings

A Distant Shore (an excerpt)

England has changed. These days it’s difficult to tell who’s from around here and who’s not. Who belongs and who’s a stranger. It’s disturbing. It doesn’t feel right. Three months ago, in early June, I moved out here to this new development of Stoneleigh. None of the old villagers seem comfortable with the term “new development.” They simply call Stoneleigh the “new houses on the hill.” After all, our houses are set on the edge of Weston, a village that is hardly going to give up its name and identity because some developer has seen a way to make a quick buck by throwing up some semi-detached bungalows, slapping a carriage lamp on the front of them and calling them “Stoneleigh.” If anybody asks me I just say I live in Weston. Everybody does, except one or two who insist on writing their addresses as “Stoneleigh.” The postman told me that they add “Weston” as an afterthought, as though the former civilises the latter. He was annoyed, and he wanted me to know that once upon a time there had been a move to change the name of Weston to Market Weston, but it never caught on. He was keen that I should understand that there was nothing wrong with Weston, and once he started I could hardly get him to stop. That was last week when he had to knock on the door for he had a package that wouldn’t fit through the letterbox, and he said that he didn’t want to squash it up (“You never know what’s in it, do you, love?”). He told me that he had been instructed by head office to scratch out the name “Stoneleigh” if it appeared on any envelopes. Should the residents turn out to be persistent offenders, then he was to politely remind them that they lived in Weston. But he told me that he didn’t think that he would be able to do this. That actually if they wanted to live in cloud-cuckoo land, then who was he to stop them? He didn’t tell this to his boss, of course, because that would have been his job. There and then, on the spot.

So our village is divided into two. At the bottom of the hill there is a road that runs west to the main town which is five miles away, and east towards the coast which is about fifty miles away. Everybody knows this because just before you enter Weston from the town side there’s a sign that says it’s fifty miles to the coast. Then after that there’s the big sign that reads “Weston” and announces the fact that we are twinned with some town in Germany and a village in the south of France. In the estate agent’s bumf about “Stoneleigh” it says that during the Second World War the German town was bombed flat by the RAF, and the French village used to be full of Jews who were all rounded up and sent to the camps. I can’t help feeling that it makes Weston seem a bit tame by comparison. Apparently, the biggest thing that had ever happened in Weston was Mrs. Thatcher closing the pits, and that was over twenty years ago.

The only history around these parts is probably in the architecture. The terraces on both sides of the main road are typical miners’ houses, built of dull red brick; the original inhabitants would have had to bathe in the kitchen, and their toilets would have been at the end of the street. However, these houses have all long since been replumbed, and the muck has been blasted off the faces of most of them so that they now look almost quaint. Mind you, the people who live down there still have to deal with the noise of the traffic at all times of day and night, and I imagine it’s murder to keep the windows clean. Besides the terraced houses there’s a petrol station, a fish-and-chip shop, a newsagent-cum-grocery store, a sub-post office that opens three mornings a week, and behind the far row of houses a pub that sits smack on the canal, which runs parallel to the main road. There’s also a small stone church, with nicely tended grounds, but I won’t be needing to go in there. Stoneleigh is up a short steep hill and it overlooks the main road. We’re the newcomers, or posh so-and-sos, as I heard a vulgar woman in the post office call us. There are not that many of us, just two dozen bungalows arranged in two culs-de-sac, but there are plenty of satellite dishes, and outside some of the houses there are two cars. Me, I don’t drive. We don’t have any shops up here, so if I do want anything I have to trek down the hill to the newsagent-cum-grocery store. Either that or catch the bus the five miles into town.

In May, I retired as a schoolteacher. Four years ago the school went comprehensive and since then standards have plummeted. It left me in a bit of a spot as I’ve spent most of my life banging on about how it would be better if kids of all levels and backgrounds could be educated together and learn from each other. It’s what Dad believed. He hated seeing the grammar-school boys in their white shirts and ties, and their flash blazers, while the kids from the secondary modern could barely find a pair of socks that matched. I can still see him shaking his head and pointing. “Class war, love,” he’d say. “Class war before they’re even out of short pants.” And then four years ago, the education authority scrapped grammar schools, turned us comprehensive, and they put me to the test. I was suddenly asked to teach whoever came into the school—we all were. Difficult kids I don’t mind, but I draw the line at yobs. But then early retirement came along to save me, and when I saw the Stoneleigh advert in the paper I thought, why not, a change is as good as a rest. Four weeks later, I found myself standing at the door to this place and handing the removal men a twenty-pound tip. I watched the dust rise and then slowly cloud as their big van pulled away. It was only six o’clock and so I thought that rather than sort through my belongings and arrange everything, I’d wander down the hill and take a good look around.

I was surprised by how busy the main road was, with big lorries thundering by in both directions. It took a good while before there was a break in the traffic and I was able to dash across. As it turned out there was not much to see, except housewives sitting on their front steps sunning themselves, or young kids running around. Doors were propped wide open, presumably because of the heat, but I didn’t get the impression that the open doors were indicative of friendliness. People stared at me like I had the mark of Cain on my forehead, so I pressed on and discovered the canal. It’s a murky strip of stagnant water, but because I was away from the noise of traffic, and the blank gawping stares of the villagers, it looked almost tolerable. The skeletal remains of a few barges were tied up by the shoreline, and it soon became clear that the main activity in these parts appeared to be walking the dog. In the fields, the cows and sheep moved with an ease which left me in no doubt that, despite the public footpath that snaked across the farmer’s land, this was their territory. I sat on a low wall underneath some drooping willow branches and looked around. The soft back-lap of the canal was soothing, although the jerky flight of a dragonfly buzzing about my head seemed out of place. This wall belonged to the village pub, The Waterman’s Arms, whose garden gave out onto the canal. In the garden some young louts and their girlfriends were braying and chasing about the place. I watched them as they began to toss beer at each other, and then shriek with the phlegmy laughter of hardened smokers. I didn’t want them to think that I was staring at them, so I turned my atten- tion back to the relative tranquillity of the dank canal, and so time passed.

As the sun began to set, and the second dead fish floated by, the silver crescent of its bloated stomach gracelessly breaching the surface, I decided that I would quite like a drink. My throat was parched, and so I stood up and walked towards the pub. I could now feel eyes upon me, and for a few moments I wondered if some of these slovenly youngsters, with their barrack-room language, weren’t pupils that I’d recently had the rare pleasure of teaching. However, I thought it best not to turn and look them full in the face, and I therefore made my way, without an escort and with eyes lowered, across the garden and up the half-dozen stone steps and into the public bar. Once inside I discovered that the small room was deserted, save for a courting couple snug in the corner, whose feverishly interlaced fingers suggested what was to come.

“Can I help you, love?” Despite the heat, the landlord was wearing a white shirt and a tie that suggested membership of some kind of club. He kept the place neat and tidy, and he’d decorated the walls with what looked like family photos and mementoes of his holidays. This stout man’s private life was on display, and I imagined that the young couple in the corner might well be holding back their enthusiasm out of respect for this fact.

“I’ll have a half of Guinness, please.” As the landlord carefully pulled the beer, I heard a loud cry and yet more jackalling from outside. The landlord glared through the leaded windows.

“Bloody hooligans.” Without looking in my direction he set the half-pint of Guinness before me. “One pound forty.” He continued to stare through the window, but his open hand snaked across the bar. I put two one-pound coins into his palm and his hand first bounced, as if to weigh the coins, and then it closed around them. “Thanks, love.”

An hour later I adjusted myself on the bar stool as he set a second half-pint before me. It was dark now, but the youngsters were still making their noise in the garden, and in the corner behind me the courting couple had set aside decorum and were now practically sitting one on top of the other. Having finished my first drink I had stood up from the stool, but the landlord would hear nothing of my leaving. “No, love, have one on the house. Call it a welcome if you like.” I still had to unpack, and the removal men had left the place in a tip, but I thought it would be rude to turn down his kind offer. I climbed back onto the stool and watched as he pulled the second glass.