Valzhyna Mort

Acclaimed Belarusian Poet

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- The Art of Translation

- An Evening with Valzhyna Mort

Biography

“Mort is most characterized by an obstinate resistance and rebellion against the devaluation of life. One of the best young poets in the world today.” —World Literature Today

“Mort’s style—tough and terse almost to the point of aphorism—recalls the great Polish poets Czeslaw Milosz and Wislawa Szymborska.” —LA Times

“Through her tightly constructed and original language, and her inspired recreation of familiar mythology, Mort attempts to resist the scourge of forgetting and to achieve immortality for her characters as well as for herself.” —The California Journal of Poetics

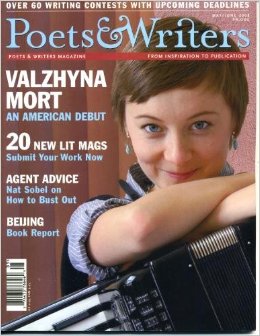

Valzhyna Mort, born in Minsk, Belarus, made her American debut in 2008 with the poetry collection Factory of Tears (Copper Canyon Press), co-translated by the husband-and-wife team of Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright. She is also the author of Collected Body (Copper Canyon Press, 2012) and Music for the Dead and Resurrected (FSG, 2020). Most recently, Mort co-translated Julia Cimafiejeva’s Motherfield (Deep Vellum, 2022) alongside Hanif Abdurraqib.

Mort received the Crystal of Vilenica Award in Slovenia in 2005 and the Burda Poetry Prize in Germany in 2008. In 2010, she received the Lannan Foundation Literary Fellowship and the Bess Hokin Prize from Poetry magazine. Her poems have appeared in Best American Poetry 2014, New European Poets, and The Ecco Anthology of International Poetry, as well as such literary magazines as The Common, Guernica, New Letters, Poetry, Poetry International, VQR and others.

There is an urgency and vitality to Mort’s poems; the narrative moves within universal themes—lust, loneliness, the strangeness of god and familial love—while many poems question what language is and challenge the authority that delegates who has the right to speak and how. The New Yorker writes, “Mort strives to be an envoy for her native country, writing with almost alarming vociferousness about the struggle to establish a clear identity for Belarus and its language.” Library Journal described Mort’s vision as “visceral, wistful, bittersweet, and dark.”

Mort is the editor of Something Indecent: Poems Recommended by Eastern European Poets (Red Hen Press, 2013), a poetic anthology that offers a conversation about how Eastern European poets view themselves, their contemporaries, their century, and the place of their region in the millennia. Together with Ilya Kaminsky and Katie Farris, Valzhyna Mort has edited Gossip and Metaphysics: Prose and Poetry of Russain Modernist Poets (Tupelo Press, 2014), an anthology dedicated to the poetics of the great generation of Russian modernists.

When asked in an interview, “How does the Belarusian landscape factor into your poetic thinking?” She replied, “The village where I spent my childhood summers, away from the city and school, is the landscape that has become my tabula rasa, the primary point of any departure. If I were to strip myself off everything, one onion layer after another, what’s going to be left of me in the end is that village. It’s unbreakable, an atom. Also, it’s the only place where freedom is possible for me. The space is open, endless, and empty, and it demands nothing of you. There is no ocean to bathe in, no mountains to climb. There is flat land, covered by wild grass, and the flat sky above it, and you can walk west, east, south, and north. That’s the greatest freedom I know and want.”

Mort writes in Belarusian and English.

Short Bio

Valzhyna Mort is the author of Factory of Tears and Collected Body (Copper Canyon Press). She is a recipient of the Lannan Foundation Fellowship, the Bess Hokin Prize from Poetry, Amy Clampitt fellowship, the Gulf Coast translation prize and the Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner Award. Born in Minsk, Belarus, she teaches at Cornell University and writes in English and Belarusian. Mort is also the author of her most recent book, Music for the Dead and Resurrected.

Videos

Publications

Motherfield

Translation, 2022

Julia Cimafiejeva was born in an area of rural Belarus that became a Chernobyl zone when she was a child. The book opens with a poet’s diary that records the course of violence unfolding in Belarus since the 2020 presidential election. It paints an intimate portrait of the poet’s struggle with fear, despair, and guilt as she goes to protests, escapes police, longs for readership, learns about the detention of family and friends, and ultimately chooses life in exile.

But can she really escape the contaminated farmlands of her youth and her impure Belarusian mother tongue? Can she really escape the radiation of her motherfield? This is the first collection of Julia Cimafiejeva’s poetry in English, prepared by a team of co-translators and poets Valzhyna Mort and Hanif Abdurraqib.

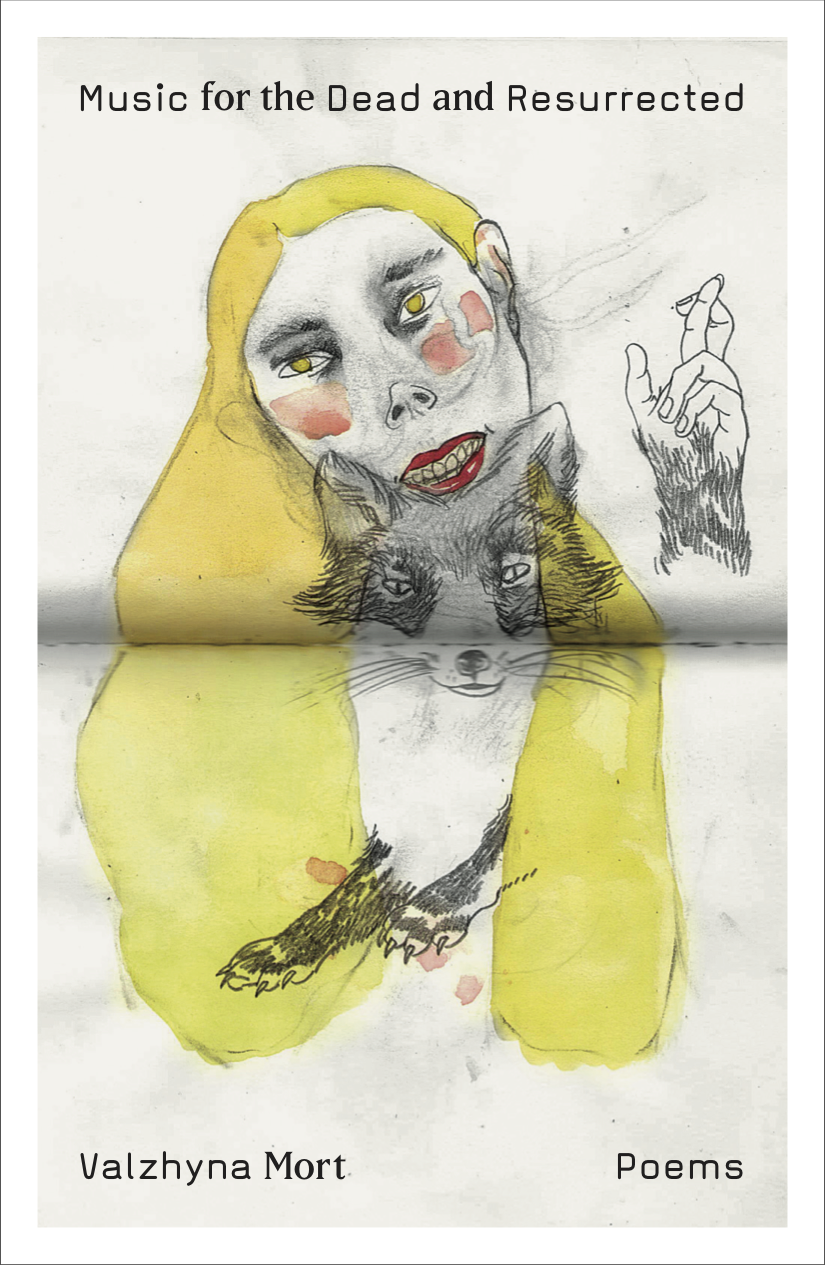

Music for the Dead and Resurrected

Poetry, 2020

In Music for the Dead and Resurrected, Valzhyna Mort asks how we mourn after a century of silence and propaganda. How do we remember our history and sing after being silenced? Mort draws on intimate and paradoxical first-hand accounts of a past grandparent generation of the Soviet labor camps, redistribution of land, and massacres of World War II in Belarus. As her country is being run by a long-time dictator, the poet creates a ceremony of myth making for the erased history and family. Music for the Dead and Resurrected is a space where the living and the dead can coexist sharing stories, where the Belarusian woods can act as witnesses of forgotten lives, and where musical form can create a new lyric mythology and an uncompromised language of remembrance. Mort, born in Belarus and now living in America, teaches us that the remembrance of private histories has a power to confront collective, violent American myths.

Collected Body

Poetry, 2012

“A one-of-a-kind work of passion and insight.” —Midwest Book Review

Collected Body‘s voyages begin in the rural landscapes of childhood and move through grim fairy tales toward idiosyncratic images of the sea, “this polonaise in gray-flat minor.” In her first collection of poems composed entirely in English, Valzhyna Mort writes as effortlessly about the Caribbean or the United States as she does about her native Belarus. Whether writing about sex, relatives, violence, or fish markets as opera, Mort insists on vibrant, dark truths. “Death hands you every new day like a golden coin,” she writes, then warns that as the bribe grows “it gets harder to turn down.”

Factory of Tears

Poetry, 2008

“Mort shows a ragged power Americans might not otherwise know.” —Publishers Weekly

Factory of Tears is the American debut of Valzhyna Mort—and the first bilingual Belarusian-English poetry book ever published in the US. Set in a land haunted by the specter of a post-Soviet Eastern Europe, and marked by the violence of the recent past, intense moments of joy leaven the darkness. “Grandmother”—as person and idea—is a recurring presence in poems, and their startlingly fresh images—desire as the approaching bus that immediately pulls away, or pain as the embrace of a very strong god “with an unshaven cheek that scratches when he kisses you—occupy and haunt the mind. The music of her lines and litanies of phrases mesmerize the reader; then sudden discord reminds us that Mort’s world is not entirely harmonious. “I’m a recipient of workers’ comp from the heroic Factory of Tears,” she writes in the final stanza. “I have calluses on my eyes…And I’m Happy with what I have.” Engaged, voracious, and memorable, Factory of Tears is a remarkable American debut of a rising international poetry star. The translation was a collaboration between Mort, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright, and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• The Best Poetry of 2020 – New York Times

• Belarus is Under Attack – New York Times

• “My Country Is Under Attack” by Valzhyna Mort – The New York Times

• Article by Mort on Svetlana Alexievich — NYT Magazine

• Interview with Valzhyna Mort — California Poetics

• A Conversation with Valzhyna Mort — PEN American Center

• In Minsk with Valzhyna Mort — Words Without Borders

Listen to Audio

• Belarus Across the Barricades – BBC

• Valzhyna Mort on endangered languages – The Guardian

• Valzhyna Reads Her Poem “Jean-Paul Belmondo” — Poetry Foundation

Selected Writings

• Read “Belarusian I” – Academy of American Poets

• Read “An Attempt at Genealogy” – Poetry Foundation

• Read “Nocturne for a Moving Train” – The Poetry Society

• Read “Guest” – Academy of American Poets

• “A Sunny Morning in the Square” translated by Valzhyna Mort – The New York Times

SYLT II

The wind that makes your hair grow faster

opens a child’s mouth full of strawberry and sand.

Slow and sure

on the scales of the ocean

the child’s head outweighs the sun.

Inside of the wind—

a blister of a church,

its walls thicker than the space from wall to wall

where the wind shifts shade and light

like two rival chess pieces

or two unmatched pieces of furniture.

Inside of the church—such a stillness

that when a feather floats down in a fist of dust

it becomes a rock by the time it hits the ground.

Organ pipes glint like a cold radiator,

contained in a case of a carved tree, its branches

tied up with a snake.

Organ pedals, golden and plump, are the tree’s only fruit.

It is all about the release of weight:

the player crushes the pedals like grapes underneath his feet.

My body, like an inaccurate cashier, adds your weight to itself.

Your name, called into the wind,

slows the wind down.

When a body is ripe, it falls and rots from the softest spot.

Only when a child slips and drops off a tree,

the tree suddenly learns that it is barren.

SINGER

A yoke of honey in a glass of cooling milk.

Bats playful like butterflies on power lines.

In all your stories blood hangs like braids

of drying onions. Our village is so small,

it doesn’t have its own graveyard. Our souls,

are sapped in sour water of the bogs.

Men die in wars, their bodies their graves.

And women burn in fire. When midsummer

brings thunderstorms, we cannot sleep

because our house is a wooden sieve,

and crescent lightning cut off our hair.

The bogs ablaze, we sit all night in fear.

I always thought that your old trophy Singer

would hurry us away on its arched back.

I thought we’d hold on to its mane of threads

from loosened spools along Arabic spine,

same threads that were sown into my skirts,

my underthings, first bras. What smell

came from those threads you had so long,

sown in, pulled out, sown back into the clothes

that held together men who’d fall apart

undressed. Same threads between my legs!

I lash them, and the Singer gallops!

And sky hangs only the lightning’s thread.

Like in that poem: on Berlin’s Jaegerstrasse

Arian whores are wearing shirts ripped off

sliced chests of our girls. My Singer-Horsey,

why everything has to be like that poem?

BELARUSIAN I

even our mothers have no idea how we were born

how we parted their legs and crawled out into the world

the way you crawl from the ruins after a bombing

we couldn’t tell which of us was a girl or a boy

we gorged on dirt thinking it was bread

and our future

a gymnast on a thin thread of the horizon

was performing there

at the highest pitch

bitch

we grew up in a country where

first your door is stroked with chalk

then at dark a chariot arrives

and no one sees you any more

but riding in those cars were neither

armed men nor

a wanderer with a scythe

this is how love loved to visit us

and snatch us veiled

completely free only in public toilets

where for a little change nobody cared what we were doing

we fought the summer heat the winter snow

when we discovered we ourselves were the language

and our tongues were removed we started talking with

our eyes

when our eyes were poked out we talked with our hands

when our hands were cut off we conversed with our toes

when we were shot in the legs we nodded our head for yes

and shook our heads for no and when they ate our heads

alive

we crawled back into the bellies of our sleeping mothers

as if into bomb shelters

to be born again

and there on the horizon the gymnast of our future

was leaping through the fiery hoop

of the sun

—from Factory of Tears