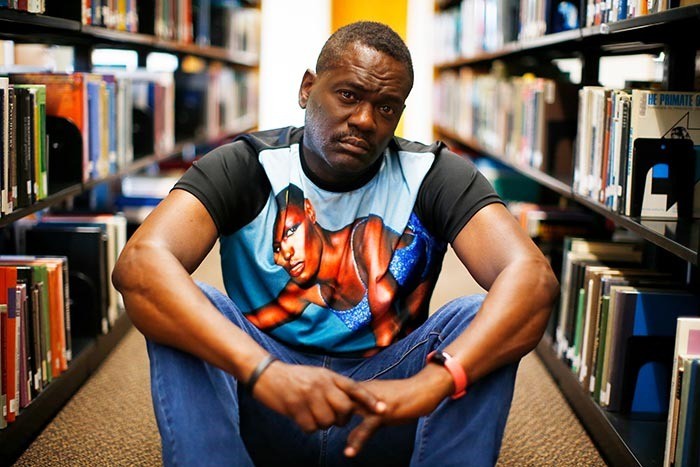

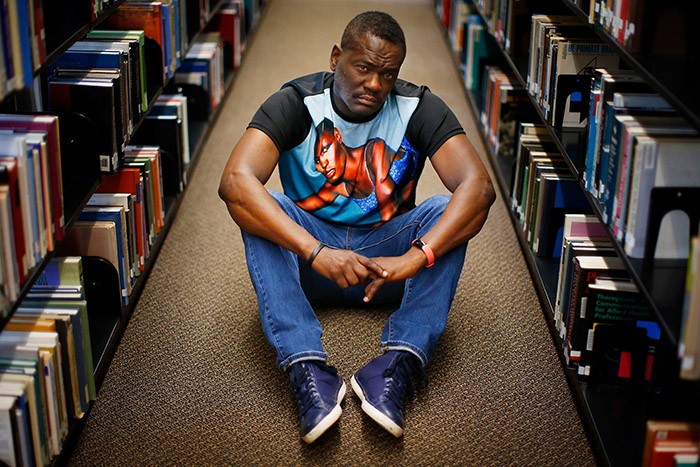

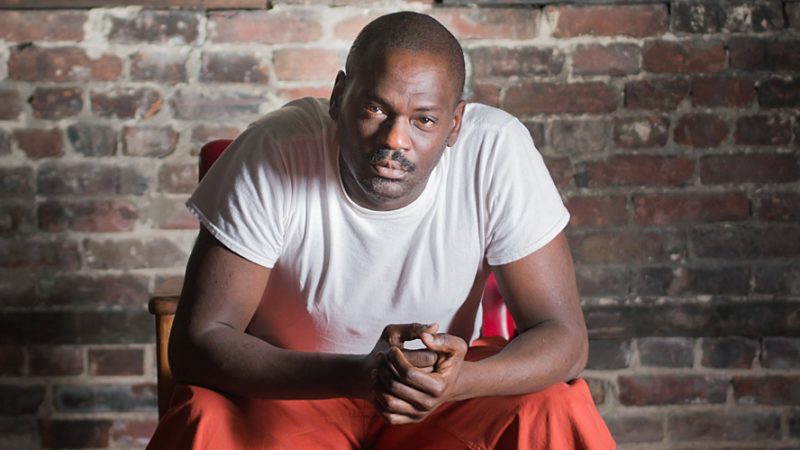

Brian Broome

Award-winning Memoirist

Readings &

Lecture Topics

- An Evening with Brian Broome

Biography

“Black, dark, queer, and poor. Brian Broome, literary son of the Black modernist giant Gwendolyn Brooks, writes from the center as one declared wrong among the wronged, one cast out of those cast aside, and one who desperately seeks tenderness.” —Imani Perry

“Furious and dazzling, poetic and gritty.”—R. Eric Thomas

Brian Broome, poet and screenwriter, is the author of Punch Me Up to the Gods (Mariner Books, 2021), which won the 2021 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction, Publisher Triangle’s Randy Shilts Award for Nonfiction, and the 2022 Lambda Literary Award in Gay Memoir/Biography. The memoir introduces Broome whose early years growing up in Ohio as a dark-skinned Black boy harboring crushes on other boys and propels forward this gorgeous, aching, and unforgettable debut. Broome’s recounting of his experiences—in all their cringe-worthy, hilarious, and heartbreaking glory—reveal a perpetual outsider awkwardly squirming to find his way in. But it is Broome’s voice in the retelling that shows the true depth of vulnerability for young Black boys that is often quietly near to bursting at the seams. Cleverly framed around Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool,” the iconic and loving ode to Black boyhood, Punch Me Up to the Gods is at once playful, poignant, and wholly original. Broome’s writing brims with swagger and sensitivity, bringing an exquisite and fresh voice to ongoing cultural conversations about Blackness in America.

About Broome’s debut, Kiese Laymon writes, “Punch Me Up to the Gods obliterates what we thought were the limitations of not just the American memoir, but the possibilities of the American paragraph. I’m not sure a book has ever had me sobbing, punching the air, dying of laughter, and needing to write as much as Brian Broome’s staggering debut.” Augusten Burroughs notes, “This is some of the finest writing I have ever encountered and one of the most electrifying, powerful, simply spectacular memoirs I—or you—have ever read. And you will read it; you must read it. It contains everything we all crave so deeply: truth, soul, brilliance, grace. It is a masterpiece of a memoir and Brian Broome should win the Pulitzer Prize for writing it. I am in absolute awe and you will be, too.”

Broome has been a finalist in The Moth storytelling competition and won the grand prize in Carnegie Mellon University’s Martin Luther King Writing Awards. He also won a VANN Award from the Pittsburgh Black Media Federation for journalism in 2019 for his article, “In the hypocrisy of the opioid epidemic, white means victim, black means addict.”

Short Bio

Brian Broome, a poet and screenwriter, is the author of Punch Me Up to the Gods. He is K. Leroy Irvis Fellow and instructor in the Writing Program at the University of Pittsburgh. Broome has been a finalist in The Moth storytelling competition and won the grand prize in Carnegie Mellon University’s Martin Luther King Writing Awards. He also won a VANN Award from the Pittsburgh Black Media Federation for journalism in 2019. Broome lives in Pittsburgh.

Visit Author WebsitePublications

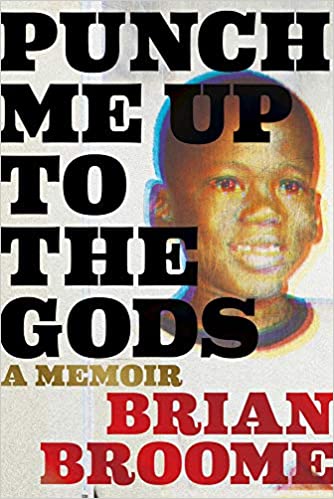

Punch Me Up to the Gods

Memoir, 2021

“Punch Me Up to the Gods is a pain-filled tour de force of incredible beauty. The writing is as exquisite as the story is at times horrific. A true work of art. Not one of the best new books I’ve read this year, but quite simply the best.” —Sapphire

A poetic and raw coming-of-age memoir in essays about blackness, masculinity, and addiction, Punch Me Up to the Gods: A Memoir introduces a powerful new talent in Brian Broome, whose early years growing up in Ohio as a dark-skinned Black boy harboring crushes on other boys propel forward this gorgeous, aching, and unforgettable debut. Brian’s recounting of his experiences—in all their cringe-worthy, hilarious, and heartbreaking glory—reveal a perpetual outsider awkwardly squirming to find his way in. Indiscriminate sex and escalating drug use help to soothe his hurt, young psyche, usually to uproarious and devastating effect. A no-nonsense mother and broken father play crucial roles in our misfit’s origin story. But it is Brian’s voice in the retelling that shows the true depth of vulnerability for young Black boys that is often quietly near to bursting at the seams. Cleverly framed around Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “We Real Cool,” the iconic and loving ode to Black boyhood, Punch Me Up to the Gods is at once playful, poignant, and wholly original. Broome’s writing brims with swagger and sensitivity, bringing an exquisite and fresh voice to ongoing cultural conversations about Blackness in America.

Articles & Audio

Read What’s In Print

• In the hypocrisy of the opioid epidemic, white means victim, black means addict. –Public Source

• In a New Memoir, the Miracle of Black Queer Self-Creation – NY Times

• The Powers of Kinesthetic Communication in Punch Me Up to the Gods – Chicago Review of Books

• An Interview with Brian Broome – PEN America

• Brian Broome Wants to Change the Way We View Masculinity – Shondaland

• Ten Questions for Brian Broome – Poets & Writers

Listen to Audio

• Author Brian Broome is keynote speaker at the annual LGBTQ literary festival in Gulfport – WUSF News

• Love Letter To Black Boys: Memoir Explores Masculinity Against Appalachian Backdrop – NPR

Selected Writings

PUNCH ME UP TO THE GODS (an excerpt)

He leans down close at the Holiday, one of my go-to bars, and whispers in my ear, “Do you play basketball?” The softness of his voice tickles my earlobe. I look up at him from my barstool.

After he asks, he leans back and folds his arms as if he already knows the answer. He bites his bottom lip and lets his eyes run the whole length of my body until they meet mine.

“You must play basketball.”

I can see that he’s already picturing it in his mind’s eye. He is already picturing me on the court in matching shorts and jersey, posed with the ball in a jump shot. He is tall, and I detect a foreign accent but cannot determine where it’s from. He has seen American basketball, he says. I am afraid that he will start to talk about it using specifics to which I cannot respond, but he only seems to know players’ names. They are names that I have heard before, and so just knowing who they are seems to be enough for now. His eyes are pale blue and set behind blond lashes and fixed on me as if I am everything he has ever been looking for. He is a professor who has come to America to teach math at the university, and his accent is dripping with sophistication. He is the kind of man who doesn’t belong in a seedy place like the Holiday. I have only seen his like in movies. He hails the bartender and turns to me.

“What would you like to drink?”

“Jack Daniel’s. Neat.”

When my drink arrives, he leans on the bar next to me by the light of the jukebox. He is now talking about specific basketball teams and I cannot fake any knowledge of this, so I put my hand on his leg to distract him. His prosthetic is a surprise to me. He shifts it away stiffly and searches my eyes for signs of flight. I show none. He is easily the most handsome man to ever take an interest in me. He helps himself to the barstool next to me and continues to speak of basketball. I lean in and let what I now know is a French accent wash over me amid the din of a filthy bar and feign enthusiasm, knowing full well that I have no earthly idea what he’s talking about. “How often do you play?” I deepen my voice to its most masculine timbre and bless him with the only basketball lingo that I know. I lower my head and lift my eyes to meet his before I smirk. “Oh, I’ve been at the top of the key more times than I can count.”

He is already fascinated and leans in closer. They called that space on the gym floor where I nervously stood with the ball “the key.” I had also heard it called “the paint” and “the lane.” The key is where boys stood on either side of me at the basketball hoop like two firing squads when it came time for me to try to shoot the ball. They didn’t even show me the courtesy of a blindfold. Even if one of them had walked up behind me and covered my eyes with a pitch-black handkerchief, tying it tight in a knot behind my head, it couldn’t make my performance inside the key any more appalling. The basket may as well have been a dozen miles away and a hundred feet high. The ball, that cornerless and slippery bane, would never drop inside of it when launched from my hands. I threw like a bitch, they told me. I threw like a blindfolded bitch. I didn’t quite know where to place my feet or my hands. I tried to watch the other boys when they did it with seemingly no effort. I tried to mimic them. Even when they missed the basket, it still looked elegant, and they would all, in unison, sing “Awwww!” in a “Better luck next time” chorus that solidified their friendships and underscored my ostracism. They trash-talked each other in a competition that seemed to reward those who could be the funniest through cruelty. They did not “Awwww!” when I missed the basket. They just laughed. Bent over at the waist and holding their bellies. Heads thrown back pointing fingers at my failure. They laughed until they cried, some of them. Couldn’t catch their breath. They had a name for this torture. They called it “free throws.” But they weren’t free at all. I paid dearly for mine.

At the top of the key, I tried to hoist the basketball just over my shoulder and bend my wrist back like they did, but I couldn’t have looked on the outside the way that I looked in my head — as the laughter from the edges of the key would begin to percolate. I tried to bend my knees in the way that I saw the other Black boys do: ever so slightly. They giggled. I tried to bounce up and down on the balls of my feet a couple times the way that they did. They snickered. The coach would cover his mouth and let his head drop to his chest, and upon seeing that, all pretense and holding the laughter in would cease. I would bounce the ball once on the gymnasium floor and then pretend to be measuring up my shot. I wasn’t. I was panicking and steeling myself inside for the onslaught. I was killing time until the inevitable launch where the ball would go flying just about anywhere that wasn’t remotely near the basket. It would take off like a hawk whose hood had just been lifted into the great beyond and parts unknown. It would either barely make it to the basket or go past it. The sound of my ball hitting the backboard was an unrealized fantasy. It never went in. Not even once. And then, because the other boys were so busy laughing, it was my job to go and chase the ball down. As I did, I could hear the gym teacher ordering them to stop laughing through stifled laughter of his own.

I dreamed of the day when free throws and hoops and backboards would no longer be a part of my reality. There is no place more like hell in the world for an uncoordinated and unathletic Black boy to be than under the gaze of other Black boys inside the lane, the paint, the godforsaken key.

His name is Bertrand. He pronounces it in a way that I cannot mimic. We sit at the dark bar together over a twinkling candle like lovers, leaned over it with torsos twisted so that we can stare deeply into each other’s eyes. In his, I see cool pools of infinite blue, and in mine, he sees basketballs. He reaches under the bar to hold my hand and stroke my fingers with his thumb to test them for length as he smiles at me. He keeps his blond hair cut short and his face is a perfect, smooth oval.

I ask him where he’s from and he sighs heavily with boredom, leaving me to wonder how and by whom he’s been asked this question before. He recites the answer to the question while rolling his eyes.

“I have lived in England, France, and Germany,” he says. “I don’t want to talk about that,” he says. “Americans, they always exoticize me and ask silly questions.”

I feel dumb for asking such a pedestrian question and decide to keep it to myself that I’ve never been any farther than Detroit. But he is not interested in that anyway. He is preoccupied with taking in my body.

I deepen my voice to its most masculine timbre and bless him with the only basketball lingo that I know. “Oh, I’ve been at the top of the key more times than I can count.”

“How long have you played basketball?”

I tell him that I have played since I was a kid, which is or isn’t a lie depending upon how you look at it. The eagerness in his eyes tells me that I should backtrack. Soft-pedal it. So I look off into the distance and adopt a philosophical and serious tone. I fix my eyes on the EXIT sign over the bar door and allow it to help me to craft a lie — a lie born of the knowledge that I have acquired over the years: that these white gay men love their Black men to be the kinds of Black men they see on television, in their sports, in rap videos. Manly and unflappable. They like big Black bucks, hardened by racism, with graceful bodies chiseled by sports. I will lie because I don’t want to lose him. Because I want to show him that I am worthy. I think back to gym class and try to channel what the boys who played basketball well must have felt. I conjure up every memory of every basketball player I ever glimpsed over my brother’s shoulder as he watched them being interviewed on his television sports shows. The lie I tell is ridiculously dramatic.

“When I play ball, I just feel free, you know? I feel like I can forget my problems and just focus on playing the game. I can just let go of all my stress.”

He leans in close enough so that I believe I can feel the heat from his body. His head hovers out of focus in my peripheral vision, but I can feel him listening. He releases my fingers under the bar and rests his warm hand on my thigh.

“I get caught up in the action of it,” I continue. “All I can think about is getting the ball to the hoop. It just becomes, like … necessary for some reason, you know? I really can’t explain it, and if you don’t play the game, it’s hard to understand, you know? I just feel, like, electric when I play ball. There’s nothing else like it. I just love being caught up in the action of it all.”

I did not soft-pedal it. He falls silent for several moments while the music and chatter of the bar drone on around us. I have laid it on too thick. I shouldn’t have said that “electric” nonsense. I am certain that if I turn my head, there will be a look of incredulousness on his face, one eyebrow raised with a smirk. So I don’t look over. He begins to move his hand up and down my thigh slowly, and he is still taking in the side of my face. The EXIT sign is looking more and more inviting.

“Would you like to go somewhere else?” he asks me.

I turn to him, and his face betrays the fact that he has just fallen in love. His expression has gone serious and concerned. A deep crease between his eyebrows.

“I know,” he says, “that you have pressure in America. With ze racism.”

I agree to go somewhere else, and we both know where that somewhere else is going to be. As we head toward the door, he tells me that he knows all about American racism and that it disgusts him. Europe is far more advanced. He is happy that I have basketball to relieve my tension from the ignorant white Americans. As he opens the door of the bar, I think back to the last time I actually held a basketball. I remember how I hated it when we would play shirts and skins. I remember the techniques I employed to get myself through it.

The trick was to lag behind the group. The boys chased the ball around like a pack of dogs, all huddling together, and their every movement was dependent upon its travels. They held their hands in the air to block other players from seeing the ball’s movements. They shuffled and shifted their bodies quickly, making the gymnasium floor squeak beneath their footfalls. And always shouting.

“I’m open!”

“Over here!”

They followed it intently with their eyes as they wiped the sweat with their T-shirts and only glanced at one another to assess whether they were a threat or an ally. He who had the ball was the focus of all the attention, and so I just decided that I would never have the ball. I stayed far enough away from the pack to ensure that it would never come to me, not even accidentally. So I lagged behind the group. When they ran to one end of the court, I would follow them slowly at a jog that was basically a walk. I did not “hustle” for the ball. No one wanted me to, and that suited me just fine. I only wanted the hour of phys ed to pass as quickly as possible, but it never did.

The only thing I learned in phys ed was that my body would never do the things that it was supposed to do. My body was the worst bully that I’d ever had. It swished. My hips and wrists were too loose. My hands found their way to my face far too frequently, wrists glued together under the chin with fingers fanned out across the cheeks. My shoulders were never more than an inch from my earlobes, tense like they wanted to force the body to be as small as possible. I flounced and lumbered effeminately. Any attempts to appear more skilled were met with uproarious laughter. I tried to make my body be forceful and tried to get it to compete. But it disobeyed. It was a marionette with tangled and impossibly knotted strings. So me and my body followed behind the boys, close enough so that it might look to a passerby that I was part of the game but far enough away to ensure that the ball would never come to me. I straggled for the duration of the games, steeling myself for the very worst part of the class, the moment when my body would betray me the most. And when the gym teacher blew his whistle to signal that class was over, I knew that the worst was yet to come.

Bertrand takes off his leg when we get back to his apartment. It is jarring at first. He sits it in the corner, and it watches us like a sentinel as we make ourselves comfortable on his mattress on the floor. I try not to look at the place where it is amputated. Mid-thigh. We begin to kiss in a less frantic way than I am used to in these situations. We peel our shirts off slowly and with purpose before we both lie back on the mattress. He uses his hands too roughly against my skin, pressing against the flesh with seemingly all of his strength. He speaks in rapid French that, to me, makes the entire encounter seem less like we’re lying on a floor mattress in a messy apartment. I do not know what he is saying, but it makes me feel romantic. I stand to remove my pants, and he is looking up at me smiling, still speaking in French. The only word that I know is noire.

They started to make us take showers after gym after puberty raided our bodies and we all began to stink. I never worked up a sweat and didn’t see why I should be made to shower. I pleaded this case, which fell upon the gym teacher’s deaf ears. Everyone had to shower. The English teacher who had us after gym class had made it clear that she couldn’t take the stench anymore.

So we were made to get naked in front of each other and given no instructions as to how to maintain our dignity. I lagged behind and took extended drinks from the water fountain. I opened the door of the locker room to a blast of steam and a chorus of hoots and hollers. The boys took to communal nudity like ducks to water. They reveled in it. Jumped around making their penises bounce. They did horseplay as if they had been naked in front of each other for their entire lives, like they had never worn clothes before. I sat down and slowly removed my shoes. There wasn’t a lot of time for me to get wet enough to pass the test. Mr. Seifert would be in at any minute to check. I rolled my socks down and removed them painstakingly, as if they were fused to the soles of my feet. I forbade myself to look up. I kept my head aimed toward the cement floor and breathed in the smell that so offended that English teacher but made me feel dizzy. Repugnant and inviting to me at the same time. I tried to hold my breath, which resulted only in my having to inhale a potent blast of it eventually. The smell was wet earth, sour but with a perfume underneath that I could not identify but that captivated all my senses. I would sit there and smell it all day long if I could, and I inhaled it with my head swimming and undressing as slowly as I could because the body I was using was betraying me even as I sat there. I could feel it wanting to make public what I had worked so hard to keep in private. I was terrified to look up. Their faces would know what I was thinking. But I didn’t know what I was thinking. I couldn’t trust my hands for fear that they would do something without my consent, like they did almost every night. Quiet so my brother couldn’t hear. My body felt recalcitrant and evil. So I made my way through the steam and stared down at their bare feet, all with toenails in need of clipping. Boys were disgusting. I turned the water on as hot as I could make it. I took the towel with me to cover my midsection. My mother would ask me later why the towels she sent me to school with came back so wet. Most of the other boys would leave as soon as I entered. I stood under the water for as long as I could and tried to scald the thoughts away. It never worked. But I stood there trying desperately to wash away thoughts of sex.

My hand only grazes the place where Bertrand’s leg has been taken. I want to look down and take it in. I want to see it, but it would be rude to look. Instead, I look down and take in the whole scene. One leg where it should be and beside it, an absence. He tells me how firmly I am built. How manly and strong. “I would love to see you play basketball,” he mumbles through lips entangled with mine. “I would love to see you on the court. You are probably amazing.” His breath comes faster as he talks about it. His eyes are closed and his head thrown back against the pillow. “I would love to see you play,” he says again. I am swept up in his pale beauty, coasting on a wave of lust that makes it easy to lie. I plant kisses down his neck and on his torso as I assure him. “You will,” I say panting. “You will.”

The white boys generally ignored me at school. Once it was determined that I was in no way able to increase their cool factor, they left me alone. They ignored me like they ignored the Black girls. They had no use for either of us. It was the white girls who got all of the attention. The pretty ones. I caught myself on occasion wishing that I were one of them. I wanted long, flowing hair and alabaster skin. I wanted to be loved the way that they were loved by everyone, especially the Black boys, who couldn’t seem to keep away even though the unspoken rules about that sort of thing were clearly established.

But the Black boys hated me. They seemed to think that I was somehow tied to them. Representative. They despised the way that I made them look. They wanted everyone within earshot to know that I was not one of them. I was a birth defect. Their cruelty outshined that of even the white kids at my school. They were compelled to distance themselves from me at all times. They wanted everyone to know that.

“He a faggot.”

Glenn Banks was turned around backward in his seat on the bus. I looked up to see him smiling malevolently and pointing the entire bus’s attention toward me with his accusatory finger. His hair hung loose and greasy in its Jheri curl.

“He a faggot, y’all. Y’all should see him in gym. Don’t nobody even wanna shower cuz he be in there.”

A couple girls snickered. And Glenn took this opportunity to press further. “He run like a bitch. Even Mr. Seifert be laughin.’”

At this, there was more snickering. Anger welled up in me but was quickly mixed with shame. Every muscle tightened against what was sure to come next. My face went numb, and all I could hear was the whoosh of the blood inside my head against the laughter that was now rising.

“Hey, Brian. You a faggot? Is you?”

He asked like he really expected me to answer. “Is you a fag?” I looked up again, hoping to give him an angry look that would deter him, but whatever I managed to produce on my face didn’t derail him in the slightest. He asked again, looking directly into my eyes. Challenging me.

“You a faggot, n – – – -?”

I scanned the bus. Some kids stared down at their laps with embarrassment for me. More were looking right at me with their mouths agape, waiting for me to answer the question. Or fight. I did neither. Near Glenn sat my brother, whose eyes were cast down. He didn’t dare look up. Glenn was his friend. They played basketball together. For a moment, I believed that he would spring into action and we would both take on Glenn together and that would be that. After we beat him, I would never have to face this kind of humiliation again. But he just sat there, overcome with the mortification of even knowing me. Glenn continued until he got bored. When we got to our house, the bus stopped and let me and my brother out on our doorstep. He turned his head toward me and glared with a boiling hatred, his fists balled up at his sides. He flung open the house door and stormed inside, leaving me there to watch the bus roll on. A sob caught in my throat, and I swallowed it. He hated me. Black boys hated me. All of them. From my father to my brother to Glenn Banks. They were all a source of pain, and much like my Judas of a body, the basketball, and the key, I wished I could be free of their demands.

I tried to make my body be forceful and tried to get it to compete. But it disobeyed.

Bertrand has asked me to meet him for a date in Squirrel Hill. The good neighborhood. We have been seeing each other on and off for about a month. He is terribly busy, and I try not to bother him, but when he calls, I am elated. He wants me to meet him at the corner of Murray Avenue and Hobart Street. I wear one of my masculine outfits. A tight-fitting T-shirt and baggy jeans that all but cover my newly purchased Adidas tennis shoes. I know that he likes this. I look the part. My body is muscular like an athlete’s. As I’m scanning the street, guessing which restaurant we might be going to, I see him come around the corner looking radiant. The sun, which is setting behind him, has been playing with his hair, making it paler in some places, darker in others. He has tanned since the last time I saw him, and my mind is already racing with thoughts of later when we are alone. His prosthetic leg gives him a peculiar gait, but I can detect a bounce in his step. He is wearing a large backpack. As he gets closer, I can see that he’s smiling at me with all his teeth — a smile so singularly focused that it makes his blue eyes squint. No one has ever been this happy to see me. He gives me a full kiss on the lips, which I don’t mind him doing in Squirrel Hill. He grabs me by the shoulders.

“We are going to play basketball.”

“Excuse me?”

“We are going to play basketball. There is a basketball place here.”

I look around and see no “basketball place” and then look back at him smiling, sure that he is joking.

“I don’t know of any … ”

“It’s just up here on Hobart Street.”

He is exhilarated and already walking in that direction. I follow him, still uncertain of what’s happening. He is talking at a rapid pace and walking quickly with his slight limp. He’s waited so long. I lag behind as he chatters about seeing my moves. Just ahead, I can now see what he is referring to. The picture comes into full focus. We are approaching a playground — the kind of playground they have in rich neighborhoods, with colorful swing sets, sliding boards, and seesaws all placed carefully atop soft sand. It’s the kind of place with kelly-green tennis courts marked off with stark white lines with stark white people running back and forth. It’s the kind of playground with pristine and smooth basketball courts, unmarred by cracked pavement. He stands at the entrance and smiles back at me.

“You know zis place?”

“Yeah. I’ve been here a bunch.”

I am still lying. I have been lying for a month. I have been putting him off for weeks. It never actually crossed my mind that this could actually happen. It was all just talk. I told him that I was sort of a star on my high-school basketball team. I fed him my brother’s life, with all the awards and accolades that he received. I told him of an injury that I’d never sustained. I filled his head with stories of how I was “too competitive.” I look around the courts and see that there is a group of boys already engaged in a game. Anxiety is creeping its way up my back, and my ears are starting to ring.

“I don’t wanna cut in on their game,” I explain. “It looks like it’s already in full gear.”

“Zis is no problem,” Bertrand says. He reaches inside his backpack and pulls out what looks to be a brand-new basketball and holds it aloft. Its burnt color and black ribs temporarily blot out the sun. He tosses it to me with his chest and I catch it, holding it away from my body like a baby that’s soiled itself. He starts over toward a park bench, and it is then that I realize that Bertrand doesn’t want to play basketball with me. He wants me to play basketball for him. I take a deep breath and try to think of a way out of this. I shout at his back about my injury, and he tells me to just “take it slow.” He just wants to see my moves.

He sits himself down on a bench so that he can watch my Black athleticism. My Black athleticism will turn him on. I bounced the ball once, hoping that it would cooperate. It returned to my hands dutifully and promised to behave itself. I thought for a moment that maybe I could pull this off. Maybe, after all these years, my Black basketball gene would show its obstinate face, just in time to save me from looking a fool. I bounced the ball again. Again, it returned. I turned to the hoop, and all hope drains from my body. I tried to toss it.

It is as if the basketball wakes up and realizes that it was caught in the hands of the exact wrong person. It pitches in my grip. Falls backward when it’s meant to go forward. I try. Oh Lord, how I try to make that thing behave. The ball, desperate to get away from my incompetence, rises up against me with a petulant hatred. It bounces between my legs, causing me to look backward after it and go chasing it down the court. Once caught, I accidentally kick it, hunched over in a ridiculous display of ineptitude. I kick it, chase it down again, and attempt to hold it aloft in my best “I meant to do that” pose. I launch it toward the basket in a foppish toss and it bounces away and I chase it again. It jumps from my hands again and bounces toward Bertrand, who is looking more and more distressed with each fumble. The ball has it out for me, wants no part of me, and twice strikes me in the nose. I cannot dribble the ball without looking at it. I don’t dribble it so much as I slap it to the ground over and over again. I cannot walk and slap at it at the same time. It escapes. It entangles itself between my feet. If the ball had a finger to point, it would have directed it right at me, doubled over laughing. The ball calls me “faggot” again and again until Bertrand has had enough and with a disgusted look on his face yells …

“Stop! Just … stop!”’

I pick the ball up and place it under my arm at my hip. Even after this disastrous performance, I am still trying to play the athlete. I hand him the ball. He is annoyed and doesn’t look me in the face. He returns the ball to his backpack and looks over my shoulder at the other boys who are playing basketball. He has asked me to stop for my own good, before they could see me. He slides the straps of the backpack over his shoulders and begins to walk away. I follow him dutifully. We go to dinner at a Korean place. I try to make conversation. His responses come infrequently and with monosyllabic clarity. He is behaving as best as he can for a man who is obliged to feed a con man. When the check arrives, he pays it, then we get up and stand at the door of the restaurant together. I can already see his mind working. He does not wish to go with me anywhere else. I have torn down the walls of every fantasy he constructed. I am a liar. He is struggling for an out, avoiding my eyes and looking out at the street. I won’t beg him. I’ve been here before. So I do what I do best. I lie.

“I have plans to meet some people for drinks at Pegasus tonight if you want to come.”

“No,” he says. “I don’t want to go there.”

I didn’t think he would. There is no kiss this time. No hug. He lays a hand on my shoulder, says good night, and disappears out the door. I already know not to call him anymore. There is a bar on the other side of the restaurant. My body walks toward it. It’s the only thing it ever does on its own that makes me feel any better.

After my brother and I got off the school bus, he let the screen door slam behind him. I stood on the stoop of our house with Glenn Banks’s words echoing through my brain.

“You a faggot, n – – – -?”

I sat down on the step and asked myself the same question. I had to tell myself the truth. I knew that I could never be what they all needed me to be. I wondered why God had done this to me. A worm has found its way from the soil up on the concrete step to wiggle beside me. I open my palm and flatten it with my bare hand, relishing its death and feeling its guts explode. I turn my palm up and look at the mess, the tiny life I was able to destroy.

“You a faggot, n – – – -?”

Yes.